Alberta farmers who practise no-till cropping have been eligible to apply for carbon credits since 2002. We know that grasslands capture and store carbon, so why aren’t landowners with pasture getting paid for their contribution?

That’s the focus of a University of Alberta study on the environmental benefits of things such as wildlife habitat and carbon storage provided by rangelands — so-called ‘ecological goods and services’ that cattle producers have been providing to society for free, up until now.

Previous research has shown rangelands are a superior way to increase carbon storage, and that once perennial grasslands are cultivated anywhere from 20 to 50 per cent of the soil carbon is released.

Read Also

Canada’s $5B forage crop needs a closer look

Forage production is a valuable contributor to the ag economy, ranking as Canada’s third most important crop behind wheat and canola.

“When you increase temperature and oxygen in the soil, microbial activity is stimulated, which results in a net breakdown in organic matter, so carbon is released into the atmosphere,” said Edward Bork, an expert in rangeland ecology and management at the university.

Bork and his team are looking at more than 115 study sites to see how large and stable the carbon stores in grasslands across the province are, and whether they are equally distributed across the different eco-regions.

- More on the Alberta Farmer: Saving the environment one legume at a time

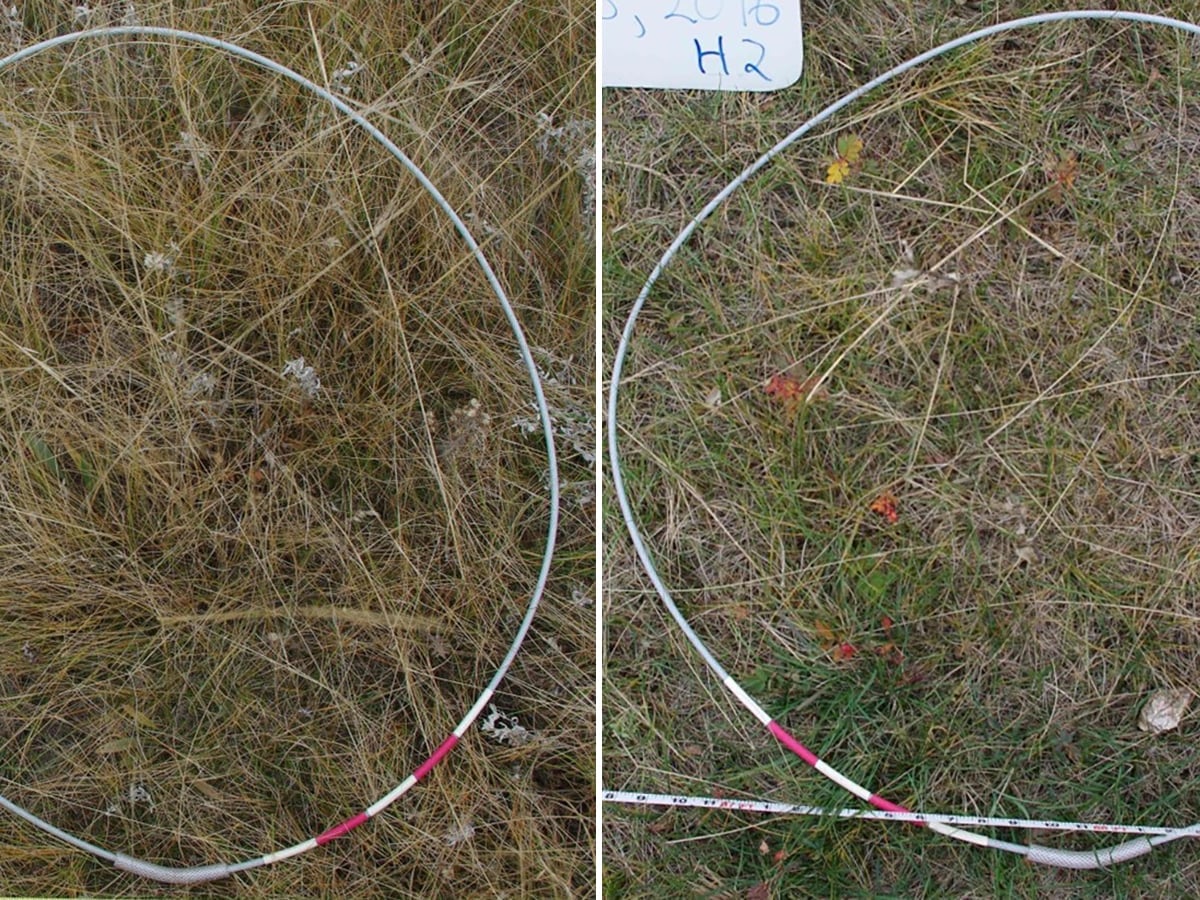

“By looking at the size and stability of carbon inside and outside of long-term livestock exclosures (fenced areas where livestock are not grazing), we can draw conclusions about livestock grazing’s effects on soil carbon,” said Bork. “We are doing this across broad agro-climatic conditions — from dry mixed grass prairie to montane to parkland environments.”

One of the main research goals is to measure the size of the benefit these grasslands currently provide.

“If we can say, ‘Look this is the benefit to society off these perennial grasslands,’ that gives livestock producers a tool in which they can go to policy-makers to say that these grasslands do more than provide forage.”

Bork is also quick to point out that grasslands provide other benefits, including wildlife and pollinator habitat and water purification.

“Once we are able to characterize the benefit of grasslands, we can then explore the next question of ‘How do we put a mechanism in place to reward producers for existing ecosystem goods and services, including carbon storage?’”

While the dollar value isn’t established yet, it’s likely to be a big number, he added.

“I would argue that in comparison to most of the mainstream alternative land uses in the settled areas of Alberta, grasslands already have the largest carbon reserve. Yet for some reason as a society we are making the decision not to recognize or reward (ranchers) for it — either maintaining or enhancing them. Why is that?”