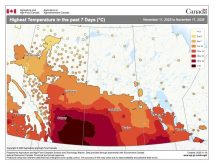

As we slowly slide into summer it seems an appropriate time to take a look at our next type of severe summer weather — heavy rainfall.

Often, when you think of severe weather and heavy rainfall, you don’t put the two together. Oh sure, the Prairies can see huge dumps of rain, but we often dismiss heavy rain because its effects are delayed — by several hours in mountainous areas and up to several days in regions with flatter terrain.

There are a couple of different types of weather warnings for heavy rain. The first is for short-duration rain events typically associated with thunderstorms, and the second for longer-duration events. In this article, we’ll look at the first type of warning, which is issued when 50 millimetres or more rain is expected to fall within one hour. It is this type of event that can come closest to bringing flash-flooding conditions, especially in cities and mountainous regions.

Read Also

Winterkill threat minimal for Northern Hemisphere crops

The recent cold snap in North America has raised the possibility of winterkill damage in the U.S. Hard Red Winter and Soft Red Winter growing regions.

What type of conditions are needed for this sort of a rainfall event? The simple answer is a strong convective event or thunderstorm. Thunderstorms need three basic ingredients to form: moisture, rising unstable air, and some kind of mechanism that helps to lift the air.

In our region, moisture for thunderstorms comes from a couple of different sources. The first major source of moisture is the Gulf of Mexico or tropical moisture. When this moisture surges northward you can really feel it as it produces those warm, humid or muggy summer days. Another source of moisture is more local and comes from evapotranspiration — the evaporation of water from the surface of the land along with transpiration of water from plants. The latter may be a fairly large source, especially in June and July when plants are actively growing.

To get really large amounts of rain, moisture has to be what is referred to as “deep,” meaning that a large portion of the atmosphere above our region has significant amounts of moisture. It is referred to as precipitable water, and is measured by stating the amount of rainfall that would occur if all of the moisture over a region fell as rain all at once. When there is a lot of deep moisture across our region, we can typically see this value in the 50-millimetre range, but that doesn’t mean this is the greatest amount of rain that we can see.

As warm, moist air rises, it begins to cool and the water vapour starts to condense. This not only starts the process of producing raindrops, it also releases heat. This heat will help the air to continue to rise. If the rising air stays warmer than the air around it, we say the atmosphere is unstable and the rising air will continue to rise on its own.

If the rising air doesn’t stay warmer than the air around it, then we need some kind of lifting mechanism to keep it moving upward. For the most part, in our region, this comes in the form of a warm or cold front. As a thunderstorm develops, the rising air pulls more and more of the surrounding air into the storm. This can greatly increase the amount of moisture in the storm. Think of it like a giant vacuum pulling in moist air and then condensing the moisture out of it and letting it fall as rain.

Fortunately, most thunderstorms self-destruct fairly quickly as the rising air piles up at the top of the storm and then eventually collapses back down, stopping the rising of additional air. Thunderstorms also tend to move along fairly quickly, so while they may produce very heavy rains they don’t last long, either due to the storm self-destructing or quickly moving out of an area.

So why can we sometimes get huge amounts of rain from a thunderstorm? There are two reasons.

The first one is the obvious one, and that is, sometimes thunderstorms can move very slowly or even stall out over a region. When this happens the storm can still self-destruct, but by the time it does it has had enough time to drop 50 millimetres or more rain over a region.

The second way thunderstorms can produce large amounts of rain is when they “train.” This is when a series of thunderstorms form and move over the same region. One storm will develop and bring heavy rain and as it starts to move off and self-destruct, a second storm quickly develops and moves in to replace the first storm, and so on. From the ground it will often seem like it is just one big storm that keeps on going. Heavy rain develops, there is a short lull, and then it picks up again. Training thunderstorms can and have resulted in very heavy amounts of rain.

In the next issue, we’ll look at conditions that bring longer-term heavy rainfall events, like the one that brought record flooding to southern Alberta back in 2013.