A series of droughts in the ’80s was a defining event for a generation of Alberta farmers.

But two producers who farmed through those times have a hopeful message: Better technology and management practices have put farmers in a much better position to handle extreme weather.

“In the mid-’80s — 1982 through 1985 — we had huge droughts throughout southern Alberta and we only combined five- to 10-bushel wheat and barley. It was very devastating,” said Gary Stanford, who farms near Magrath.

“In 2020 we had one of the best crops we ever had yield-wise and then (in 2021) it was one of the worst crops we ever had. But even with the huge drought, with our better farming technologies and the better ways we seed our land now we were still able to combine 20- to 30-bushel crops in the area where I’m at.”

Read Also

Lethbridge research farm lease renewed for 20 years

Lethbridge Polytechnic and the Government of Alberta have signed a 20-year renewal of a land lease agreement for the institiution’s research farm.

But it’s important to first recognize that farming lessens the ability of land to withstand drought, said Morrie Goetjen, who ranches in the Cremona-Cochrane corridor west of Calgary and is a director of the Foothills Forage and Grazing Association.

“The one thing we’ve done in the past 100 or 100-plus years in this part of the world is we’ve exposed the land for it to be drier,” he said. “Conventional farming — as necessary as it is and as important as it is — reduces moisture content in the land. It just does.”

Given that, producers should continually be looking for ways to mitigate the impact of those practices.

“We at Foothills really advocate for cover crops and we really advocate for zero-till seeding,” he said. “Personally I subscribe and advocate the (holistic management pioneer) Allan Savory methods of rotational grazing.”

The memories of the ’80s droughts are still clear in Stanford’s mind as they started not long after he bought his own land.

“In about 1982 and then into 1983 we started seeing the huge droughts in southern Alberta and southern Saskatchewan,” he recalled. “We would literally get only one inch or two inches of moisture from April to October each year.”

But crop farming was hugely different.

“Back then we still cultivated,” he said. “We didn’t have the good herbicides and protection products that we have today so we still cultivated to kill the weeds and then when we did that we lost the moisture from the winter snows.”

It was also a time of high interest rates, and the combination of those three things were too much for many.

“There were a lot of farmers who foreclosed on their land,” he said. “It was a giant snowball effect. The way I was able to keep going is that the government had a program to help keep the interest rate low for young farmers at that time.”

Of course, it helps, too, that prices have been so high in the past year, which is partly tied to the fact that drought was more localized four decades ago.

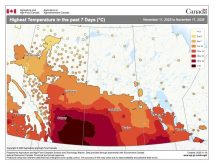

“We would have a little bit of a bump in price (in the ’80s) — maybe $1 per bushel — but nothing like it is today,” said Stanford. “The reason for that is there were still good crops in the U.S. or anywhere but the Palliser Triangle in Western Canada whereas this year, the drought covered pretty much all of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.”

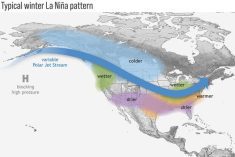

Thanks to his proximity to the mountains, Goetjen said he lives in a particularly blessed area in terms of moisture.

“We don’t get drought like they get out east or down south,” he said. “We’re kind of in that sweet spot between the moisture and the colder air to the north. We’re close to the mountains so we get shower activity no one else gets.”

But he remembers the late ’80s in particular for its series of dry summers with little snow in the winters. Capturing snow and holding on to it is important — even a thin cover of the white stuff helps.

“If nothing else it helps to preserve whatever moisture is in the ground and keep it from drying out,” said Goetjen. “A big part of drought mitigation is not losing that moisture in the winter.”

One similarity between the summers of 1988 and 2021 was the appearance of rain close to harvest.

“The same thing happened in 2012; the rains came late and kind of saved the day. But this year it was a little bit later and the rains weren’t nearly as good or as widespread.”

As stressful as farming can seem today, Stanford said he would never want to trade places with his younger self. In addition to better agronomic tools, there are more marketing options today, such as no wheat board as well as a greater ability to pre-sell or hold grain, he said.

“It was way harder farming back then,” he said. “Today it’s quite a bit easier and I think that’s helping with some of our yields. I know there’s been a lot of bad yields but we can control our destiny a little better.”

But as in the past, Mother Nature calls the shots.

“This was a terrible drought this year but it’s not unusual to southern Alberta and the Palliser Triangle,” said Stanford. “We’ve always had them and we will again in the future, but I’m hoping that it doesn’t continue on next year.”