It’s the best thing that ever happened out here.”

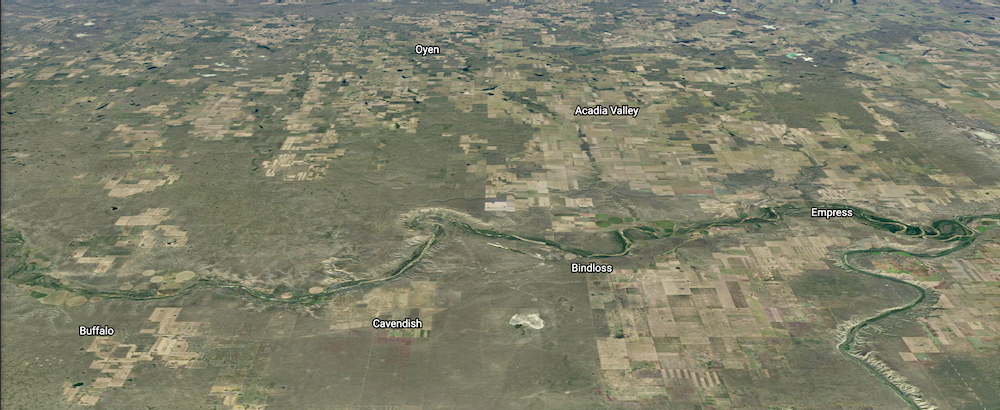

That’s how farmer Daryl Peers describes a proposal to spend as much as $1.3 billion to irrigate up to 108,000 acres in the Special Areas and Municipal District of Acadia.

And while the project is far from a done deal, it’s desperately needed to rejuvenate the economy in east-central Alberta, says Acadia’s reeve.

Read Also

Farmfair International boosts accessibility with weekend schedule shift

Farmfair International is changing its scheduling format to include the weekend and hopefully attract even more attendees.

“This part of the province has been struggling to keep people, and our ability to support communities has been declining over the past 20 years,” said Peter Rafa. “The good-paying jobs are gone. (This) would bring some opportunity back for all the people in our community and the surrounding area.”

Earlier this month, the province, the Canadian Infrastructure Bank, and local governments made a low-key announcement saying they would spend $7 million “to continue the planning of a large-scale irrigation project.”

In fact, if the preliminary price tag proves to be accurate, it would be the most costly irrigation expansion in the province’s history, topping the $933-million project now underway in southern Alberta that will put an additional 230,000 acres under irrigation.

[RELATED] Alberta eyes another blockbuster irrigation project

The per-acre price tag for the new project, which would tap the Red Deer River for water, is higher, with an initial consultants’ report pegging the cost at $12,300 per acre. It proposed that in addition to provincial grants, a loan from the Canadian Infrastructure Bank (a special federal lending agency), and unspecified “equity from the private sector” would be part of the funding. Farmers would pay some of the costs via an upfront “capital asset charge” of $2,500 to $5,000 per acre.

Although they would prefer to keep that on the lower end of the scale, Rafa said producer response has leaned strongly in favour of getting it done.

“I think it’s unfair to call it a capital asset charge,” said Scott Heeg, who farms in the MD of Acadia. “They refer to capital asset charges in irrigation districts as the buy-in for farmers buying more irrigable land, while this is the cost the farmer is going to agree to in order to get this project off the ground.”

On top of the capital asset charge, the report recommended an annual irrigation charge of $100 to $140 per acre, a sum considered significantly higher than in other irrigation projects.

The project will be expensive but necessary if the region is to have farming and other industries in the future, said Peers, who farms land in both the MD of Acadia and the Special Areas.

“It’s going to be way more money than I want to spend, but it’s good for our kids because they’ll get it back,” he said.

Long road ahead

The report prepared by Calgary consultants WaterSmart declared the 108,000-acre project feasible, but said there is much work to be done before it can get a green light.

The $7 million for the feasibility study will cover some preliminary engineering design, and also look at environmental and regulatory considerations and potential financing options. That is expected to take up to two years, with regulatory reviews and construction taking nearly a decade more.

[RELATED] Irrigation districts laud provincial support of sector

There are also no guarantees on the scope of the project.

The 108,000-acre scenario represents its maximum size – 49,200 acres in the MD of Acadia and 58,900 acres in Special Area No. 2. A more frugal option involves 81,000 acres, which would remove the highest-cost land to irrigate. That would bring the estimated cost to just over $1 billion. Cutting it further to 49,200 acres, by developing in the MD of Acadia only, would reduce the cost to $387 million.

“That’s what this next phase is about, taking the concept that was initially developed around this 108,000 acres and providing more details behind it and more analysis on some of the engineering considerations and design considerations of the project,” said Jordon Christianson, chair of the Special Areas Board.

WaterSmart estimated the increased crop production and spinoffs, such as new food processing facilities, could add $3.9 billion to the provincial economy over 30 years and generate nearly $1 billion in federal and provincial tax revenues.

But the project must be affordable for farmers if it is to move ahead, said Heeg, who serves on the MD of Acadia council.

“I’m really optimistic that we can fine-tune that number and get that initial start-up cost down a little bit. That’ll boil down to negotiations with the government of Alberta and the Canadian Infrastructure Bank … so it is something the farmer is able to handle and we can move forward with the project.”

‘It will be huge’

While agriculture is a mainstay in the arid region, the past five years are among the driest in recent memory.

Heeg said he’s been able to make it through the drought years with crop insurance, but his situation is becoming more precarious.

“Once you have three or four drought years on your record, your crop insurance coverage starts dropping off and you hope premiums stay similar to what they were,” he said.

“But the way (the cost of) inputs are right now, if your crop insurance margins shrink down and you’re still not growing the crop, things get pretty tight and that’s when tough decisions have to get made.”

More people are making that tough decision to leave the area, which until recently was a hub of natural gas production. The WaterSmart report projects that natural gas production in southeastern Alberta will decrease by 57 per cent by 2030. It warns that “the population in these communities is forecasted to decrease more than anywhere else in Alberta over the next 25 years.”

For those and other reasons, this project is a necessity, said Peers.

“Going forward it will be huge for the businesses in the Special Areas or the town of Oyen and (the hamlet of) Acadia Valley,” he said. “It’ll bring more people to keep our schools full. It’s huge. It should have been done 30, 40 years ago.

“There’s going to be some growing pains but the way I look at it is, if it doesn’t happen, there’s no reason anyone should want to stay out here.”

This project could reverse those fortunes and potentially attract value-added processing and people to fill those jobs, added Heeg.

“It would bring a ton of population to the area, (people doing) everything from operating on-farm to looking after the headworks system and servicing maintenance on pivots to value-added businesses.”

Water security is key

Irrigation may also allow farmers to expand into the kind of high-value crops (potatoes and sugar beets) grown in irrigation country near Lethbridge and Taber.

Farmers are excited about this possibility, said Rafa, but they may be even more relieved that this project would bring a stable source of water.

“I honestly think the farmers in this area are looking for security of the water; dependable water making it to the farm,” he said. “It’s not a far drive down that No. 3 highway to Lethbridge where you see all those high-value crops. Farmers in this area want the opportunity to grow those high-value crops because that helps pay for all the irrigation costs that we’d be doing.”

Peers is among those looking forward to the possibilities.

“We might be able to grow potatoes, sugar beets, silage corn – anything like that. It opens up a world from just lentils, peas and durum.”

Heeg takes a more cautious approach to the idea of specialty crops, although data shows some could be grown under irrigation in the area.

“Our heat units are very similar to that Lethbridge-Taber country,” he said. “The issue with some of those specialty crops like potatoes is you would have to completely retool your farm. The farm is taking on a huge amount of cost to start up (irrigating) so can you really afford to retool half your farm for potatoes and stuff like that?

“That’s a question that will have to be answered later on.”

Soil may also be a limiting factor, said Heeg.

“It’s a different kind of ground out here. It’s a heavier clay ground so some of it wouldn’t even be suited for vegetables like potatoes or beets. They like lighter soils. Guys will probably just have to experiment off the start, see what’s attainable and go from there.”