Crop insurance premiums are not rising by more than half for Alberta farmers, but they’ll likely have to dig deeper in their pockets.

The year-over-year average increase is 22 per cent, not the 60 per cent suggested in a recent Global news report, says the Agriculture Financial Services Corporation. That figure exists in the province’s fiscal report but is based on outdated information, said Darryl Kay, the CEO of AFSC. “The fiscal report is a budget. That’s why it’s talking about budgeted numbers.”

Read Also

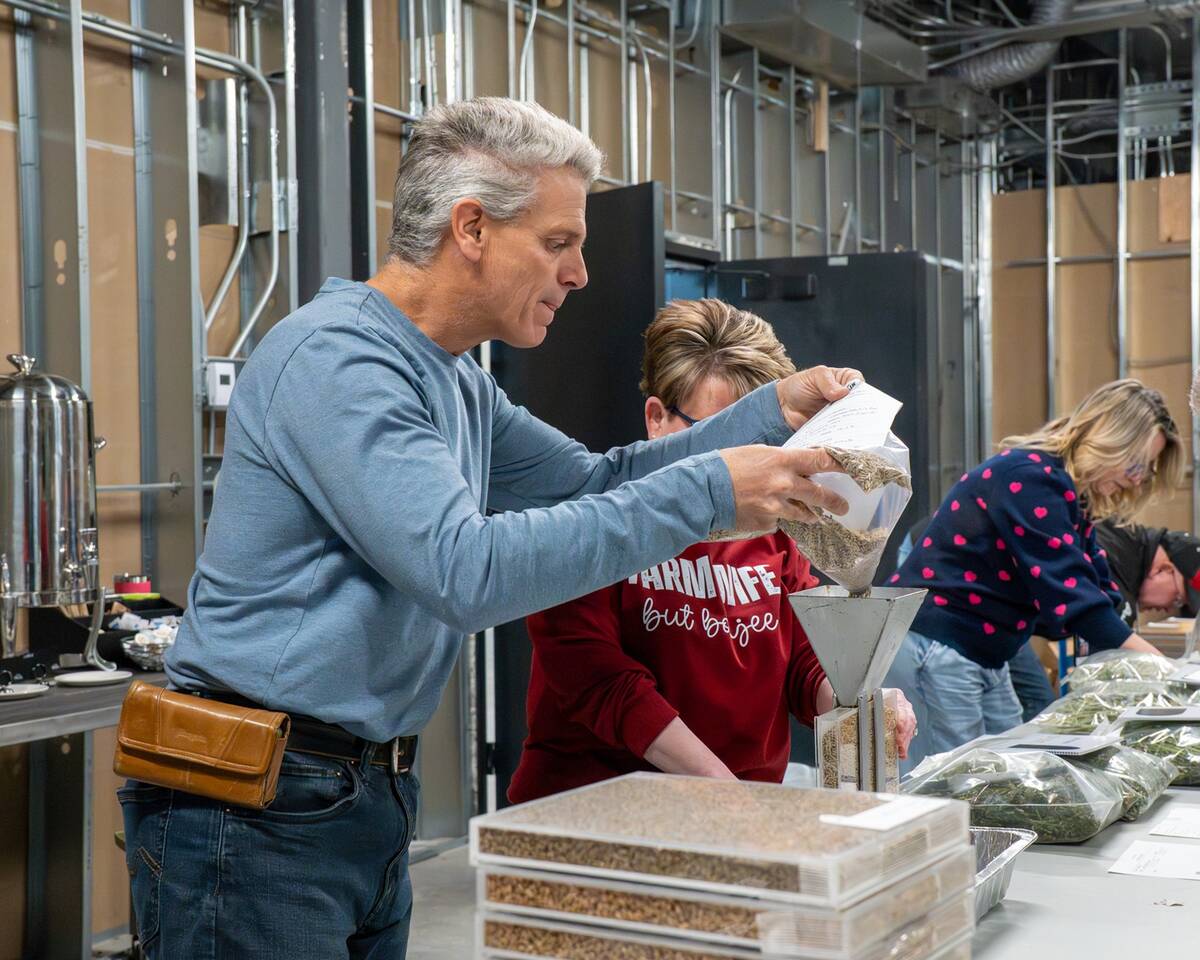

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

The fiscal report identifies a “…60 per cent increase in premium rates needed to replenish the crop insurance fund after the significant withdrawals in 2021-22 and forecast for 2022-23.”

“It’s not trying to reflect the actual premiums that producers will pay,” Kay said.

The budget number is based on estimates last fall. It points to the challenge involved in forecasting rates so far ahead of when farmers are offered their individual premiums, he said. “Eight months before the crop year is actually set, we’re trying to predict future commodity prices, we’re trying to predict participation, crop mix — all those things. So the budget is just an estimate.

“The key to focus on is the actual premiums that we set for producers, and those are prepared in the spring when we move into a crop year. That’s when we’re dealing with the right information… and we have clarity in terms of the actual premiums producers will pay.”

Kay said the difference between budgeted premiums and what producers end up paying can also go in the opposite direction, and has done so in the recent past.

“When we prepared the 2021 budget it was low compared to where we actually ended up. So while our 2021 starting point was low from a budget perspective, we saw a pretty significant increase in commodity prices.”

He said high prices played a key role in the estimates and will continue to do so as farmers’ individual premiums are calculated.

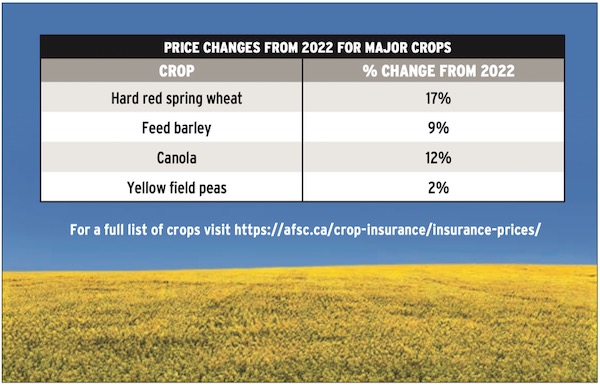

“Over a two-year period, commodity prices were up on average 57 per cent. Thinking about the major crops, canola was up about 12 per cent, spring wheat was up 17 per cent and barley was up nine per cent.

“So when we look at that 22 per cent (increase) a big portion of that is actually the commodity prices changing year over year.”

Rising participation

Rising participation in the program, driven significantly by the effects of the 2021 drought, will also play a role in premium hikes.

“From 2021 to 2022 our insurance participation actually went up over nine per cent. We had an additional million acres insured under crop insurance,” Kay said.

“The more participation we have, the more liability we take on as an insurer, which increases the amount of premium we collect.”

He said premiums are calculated based on three key components — commodity prices, long-term debt and discounts. Commodity prices greatly affect coverage.

“The higher the coverage, the higher the premium needed to secure that coverage. There is no cap on changes to coverage. This is important to make sure the program covers the appropriate risk for clients, and given the input costs and commodity prices, farmers want to be able to secure adequate coverage for their crops.”

Kay said AFSC participants are seeing their coverage double this year. Coverage went from about $4.8 billion to almost $10 billion in the two-year period. The high payouts from the drought of 2021 created significant losses for AFSC. Farmers will have to pay this back, but not all at once, he said.

“We can play the long game with that. AFSC is not striving to recover losses in a short period and uses a 25-year time period to try and ensure that rate increases are predictable and stable.”

There is a cap on this portion of the premium rate.

“This part of the premium cannot increase by more than 10 per cent year to year.”

Depending on individual farmers’ situations, discounts may be reduced. However, AFSC can only do this to a certain point.

“Any producer who had losses from 2021 will likely see their discount reduced in 2023. There is a 15 per cent cap on movement in a client’s discount or surcharge year to year.”

In addition to all that, price movement and consequently coverage change is different for every crop.

“Clients have options they can choose within the program to customize it to their needs, such as selecting hail endorsement or choosing different coverage levels,” Kay said.

These factors combined create an approximate premium increase.

“On average, if we look at actual premiums in 2022 and our forecasted premiums for 2023, the increase is approximately 22 per cent.”

Kay said it’s hard to pinpoint how all this translates into producers’ premiums because it depends so much on their individual situations. But there are some rough estimates.

“According to some of the numbers we’ve crunched, a typical canola producer will see their premiums increase from $13 or $14 to about $16 per acre,” he said.

Wayne Schneider, a Nisku-area farmer and region six director for Alberta Canola, said he was shocked when he heard the 60 per cent number reported.

“My first reaction when I heard that 60 per cent was like, ‘Oh my goodness, is that what it’s gonna be?’ I’m definitely a lot calmer than when I first read that. I think that’s where a lot of farmers got kind of concerned. Paying 60 per cent extra premiums just wouldn’t be possible.”

A big part of individual farmers’ premiums will depend on crop mix, which AFSC uses in its premium calculations, said Schneider.

“If someone is growing more canola or wheat than their neighbour, obviously theirs will be higher than if somebody’s growing some barley or yellow peas.”

Barley premiums rose nine per cent from last spring, while yellow peas rose two per cent.

“It all depends on what your crops are going to be this year. So that 22 per cent isn’t actually the correct number.”