Treating pink eye in cattle on pasture can be frustrating, time consuming and only minimally effective.

That’s why researchers with the University of Saskatchewan have completed a trial project that may set the stage for more effective treatment.

Results from the recent study, started by now-retired researcher Philip Griebel, suggest that dropping an experimental vaccine vector right into the eyes of two-month-old calves can be safe, effective and create an immune response.

Read Also

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

“The commercial vaccines that are on the market are parenteral, which means you have to inject the animals subcutaneously or intramuscularly,” said Paola Elizalde Ruiz, one of the researchers committed to the project.

Canadian pink eye statistics are difficult to find, but in the U.S., it affects an estimated 10 million cows per year, with a total annual cost of US$150 million. Properly named infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK), pink eye can hit hard at calf gains and greatly increase labour costs.

“Most calves are out in pasture,” said Elizalde. “And then, if you have an IBK outbreak, you have to bring those calves in and treat them with antibiotics.”

The average pre-weaned calf infected with IBK loses around 17 pounds and usually more if both eyes are infected.

“Some animals end up with scars, and that’s also a problem because when you want to sell the animal, you’ll get less,” the researcher noted.

Then there is the cost and limited scope of treatment. Cattle producers have few options to combat pink eye when cows start to show symptoms like lacrimation (heavy tearing) or continual blinking.

“I’ve seen some people use parenteral antibiotics or, in other cases, they put on eye patches containing local antibiotics,” said Elizalde. She put the investment cost for a round of IBK treatment at $100 per head.

Limited toolbox

Management is even trickier when it comes to prevention. First, producers face the almost impossible task of avoiding co-factors such as flies and UV light.

When it comes to vaccination, the standard control in Canada protects against Moraxella bovis (M. bovis) bacteria. American producers are also able to use vaccines containing Moraxella bovoculi antigens. M. bovoculi was linked to IBK in 2002.

M. bovis is commensal, which is defined by sciencedirect.com as an organism that eats food supplied by a host without causing harm to it. With co-factors such as UV light and flies, IBK can result.

Research conducted over the past six years does not bode well for the effectiveness of either M. bovis or M. bovoculi vaccine when administered by parenteral injection. Field trials in the U.S. and Australia have reported no difference in the incidence of pink eye between vaccinated and non-vaccinated animals.

Experimentation with intranasal vaccination has also failed to impress, said Elizalde.

“They decrease the severity of the disease, but really do not decrease the incidence. So, we wanted to go one step more and that’s why we decided to make an experimental ocular vaccine capable of inducing a protective immune response in young animals.”

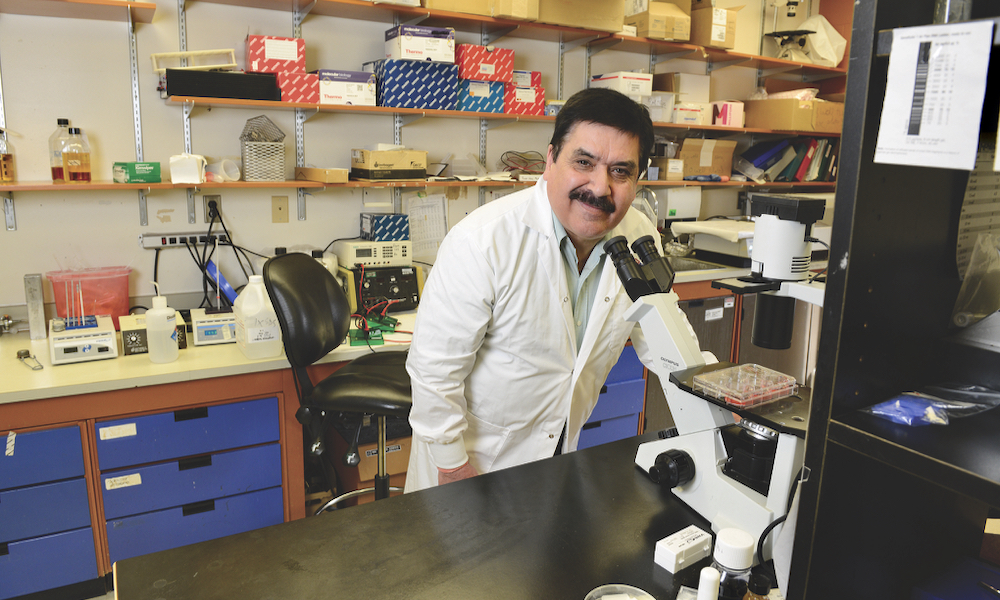

The problem with parenteral immunization is that the vaccine doesn’t reach the mucosal surfaces where there could be an immune response, said another university researcher, Suresh Tikoo.

“The antibodies produced when you are doing parenteral immunization are what we usually call IgG type. They do not cross and reach to the mucosal surfaces like the eyes or the face,” he said.

“We need a vaccine that targets the production of IgA, which is the most abundant antibody in the mucosal surface.”

To ensure the safety of vaccine in calves’ eyes, the researchers used it with a viral vector (bovine adenovirus type three, or BAdV-3) that they knew wouldn’t cause harm. Ultimately, the team confirmed that the method created an immune response in the eyes of test calves.

“When we put a drop of BAdV-3 expressing that test antigen, it produces a significant amount of mucosal immune response,” Tikoo said.

Further steps

The next stage of the project will involve testing the method with a commercially available pink eye vaccine.

“We’ll be using an actual vaccine against Moraxella using BAdV-3 as a delivery system directly to the eye,” said Tikoo.

It will likely be several years before a vaccine designed for the method becomes available to producers. That eventual commercial release will also require a mental shift for the farmer, Elizalde noted.

“Delivering a drop on the eye of cattle could sound difficult,” she said, especially when producers are already comfortable with delivering injectable vaccines. In this case, however, those comfortable methods are not working.

“This is an expensive disease and it’s very painful for animals. What we have now are measures of control like fly controls or vaccinations, but [pink eye] hasn’t been eradicated,” she said.

The project was made possible with support from the University of Saskatchewan, the Beef Cattle Research Council, the Province of Saskatchewan through its Agriculture Development Fund and the federal government through the NSERC Sustainable agriculture research initiative.