Volcanoes usually have a cooling effect on our planet. The ash and SO2 (sulfur dioxide) propelled into the atmosphere from an eruption tend to block incoming solar radiation, resulting in an overall cooling effect.

Location is also important. High latitude eruptions tend to have less impact as the ash of SO2 cannot reach as high into the atmosphere because colder temperatures thin the active weather layer atmosphere.

Volcanic eruptions near the equator have a high active layer and the upper atmospheric winds tend to disperse the ash over a much wider part of the planet.

Read Also

How Earth evens out the energy input

Earth has surpluses of radiation in its equatorial regions, and deficits toward its poles. Our weather is a matter of Earth trying to even out the imbalance, Daniel Bezte writes.

Not all volcanic eruptions result in atmospheric cooling. If it contains more water vapour and CO2 than ash and SO2, then the overall results can be atmospheric warming because these gases are good at trapping outgoing longwave radiation and have little impact on incoming shortwave radiation.

- READ MORE: Volcanic eruptions and climate

The Tonga volcanic eruption that occurred on Jan. 15, 2022, could be partly responsible for the record-breaking global temperatures in 2023. Some people who have written to me about this wish I would say it is wholly responsible for the record-breaking temperatures, but that is just not true.

The planet was into a full year of El Nino conditions across the Pacific Ocean, which leads to warmer global temperatures. Put that on top of already rising global temperatures due to human-induced warming, and it was already predicted to be a near or record-breaking year. What caught people off guard was the extreme to which the record was broken.

The Tonga eruption was one of the biggest to occur on Earth in the last 1,500 years. It was different from most other large eruptions because, on top of the large amounts of particulate matter sent into the atmosphere, it also ejected a huge amount of water vapour due to its undersea location.

It is estimated that the amount of water vapour ejected was enough to fill 58,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

On top of this, the eruption was powerful enough to push water vapour through the active layer, or troposphere, and into the stratosphere. Researchers estimate there was a 10 per cent increase in the total water vapour in the stratosphere. It is also estimated that this water vapour will remain there for several years.

This eruption was so efficient at pushing water vapour into the atmosphere because of its depth. At about 150 metres, a large amount of water was above the volcano, but not deep enough that the pressure of the water would mute the power of the explosion.

Water vapour is a very good greenhouse gas, much better than CO2. Water vapour accounts for about 60 to 70 per cent of the greenhouse effect, while CO2 accounts for about 25 per cent. Methane, on the other hand, is more potent than either of these, but that is for another article.

The real question is how much impact did the Tonga eruption and release of water vapour have on global temperatures. Research published in January in Nature Climate Change indicated the eruption likely resulted in a 0.035 C increase in global temperatures.

That’s far short of the 0.17 C difference between the old global temperature record and what was achieved in 2023.

What is the long-term impact of the stratospheric water vapour? We are not sure. The latest research suggests stratospheric warming only makes up about five per cent of the total amount of surface warming. Any significant increase in the amount of stratospheric water vapour would only account for a small increase.

Research predicted that global temperatures would likely surpass 1.5 C sometime in the next few years, but the increase in global stratospheric water vapour has increased this probability.

In case you are wondering, 1.5 C is not a magical number. It was the number set by the Paris Climate Accord in 2015. It was optimistic that we could avoid a 2 C increase in global temperatures before 2100 by avoiding this 1.5 C target.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report found that at this temperature (1.5 C warmer), extreme heat is significantly less common and intense in many parts of the world than at 2 C.

At night, the coldest nights at high latitudes warm by around 4.5 C when the world is at an average of 1.5 C warming. That figure is especially important for the future of sea ice in the polar regions. At 2 C warming, the coldest nights warm by around 6 C.

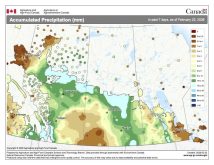

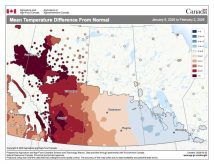

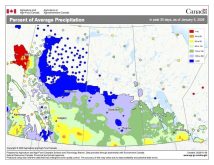

While this winter has been anomalous across the Prairies due to El Nino, this warming of the coldest night by around 6 C really resonates.

Overall, the Tonga eruption did contribute to last year’s record-breaking heat across the planet, but it doesn’t appear to be the main cause. Rather, it was one of several things that resulted in record heat.

If you have any questions, fire away. You can reach me at: [email protected].