In the last issue we did our monthly weather review and then looked ahead to see what the different long-range forecasts were predicting for the upcoming months.

One weather model was not ready at that time, and that was the Canadian CanSIPS model. Its latest forecast is calling for near- to above-average temperatures in September and October, with western regions being the warmest compared to average and eastern regions being the coolest compared to average. November temperatures are predicted to be near-average.

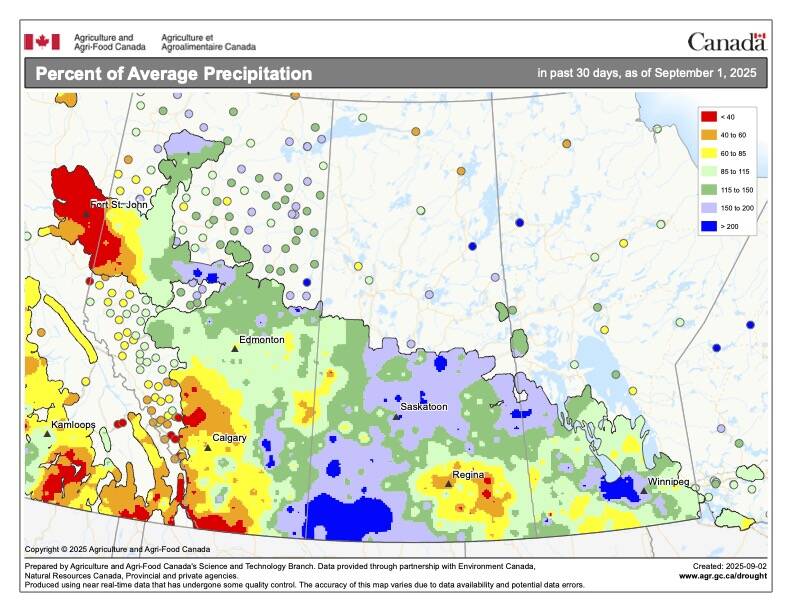

Their precipitation forecast calls for near-average amounts across all three months, with northern Alberta seeing below-average amounts in September.

Read Also

‘Devastating’: PMRA blocks Alberta’s joint emergency strychnine bid

Agency rules proposed mitigation measures insufficient to lower environmental risk, despite growing Richardson’s ground squirrel population.

In this issue, we are going to wrap up our look at extreme rainfall by looking at the different weather patterns that tend to be associated with these rainfall events. We’ll also examine how changing weather patterns may contribute to these events.

Extreme or heavy rainfall can happen from many conditions, but often it is a combination of specific conditions that leads to record breaking rainfalls. For example, you could have training thunderstorms, but if there is not much available moisture then you will not get extreme rainfall. You could have a strong area of low pressure, with lots of moisture and plenty of instability — but it if is moving fast then rainfall totals will not be that extreme.

Looking at all the one-day rainfall records, they all occur in either June, July or August, which just happens to be thunderstorm season. Thunderstorms that bring extreme rainfall usually have several conditions that come together to produce extreme rainfall. There will be plenty of moisture, atmospheric instability, some form of front providing lift, and then slow speeds or training of storms.

The two main conditions that are almost always needed to be present for extreme rainfall are plenty of moisture and slow movement of systems.

With changes that our atmosphere is currently undergoing due to a warming planet, these two conditions look to become more prevalent. A warmer atmosphere and ocean is leading to an increase in the available atmospheric moisture. Now this doesn’t mean we won’t have dry conditions. Sure, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, but if the atmosphere is dry that means the increased heat will be able to pull more moisture out of a region through evapotranspiration.

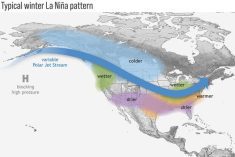

Overall, it looks like the atmosphere can and will hold more moisture and that moisture will be available to produce rainfall. There is also emerging evidence that a warming planet is leading to a slowing down of weather systems and the development of more blocking patterns. Blocking patterns are when certain configurations of highs and lows develop that tend to not move much, or they block the movement of weather systems — thus the term blocking pattern.

We often remember blocking patterns when they bring long periods of warm dry weather, but they can also bring long periods of cool wet weather. It all depends on where you are in relationship to the block.

Why the slow down? To put it into simple terms, as the planet warms, the poles warm significantly faster than the equatorial regions. This lessens or weakens the temperature gradient between these two regions. It is this temperature gradient that is the driving force behind most of the atmospheric circulations such as the jet stream. As they weaken systems will move slower and the pattern become more meandering.

Think of a river. If it is flowing down a steep hill it tends to stay relatively straight, when it is flowing slowly across a flat region, like the Prairies, it meanders. The same thing happens with the flow of the atmosphere and when it gets curvy it can get stuck in that curve until that curve breaks off — much like rivers and oxbow lakes.

Are we going to continue to see a continuation of the slowdown and more meandering and blocking patterns in the future? I think so. Chances are we will see more of the shifting between dry and wet patterns. Sometimes it will be within short time frames — dry one month and wet the next — and other times over longer periods where we will see a season or year or two that are dry, followed by just as long wet periods.

This is what is making long-range weather forecasts much more difficult. Weather models rely partially on past experience — what happened in the past when a certain weather pattern was present. The problem now is that the atmosphere is not behaving the same way as it did in the past, and in my opinion, things are going to get more uncertain over the next few decades.

In upcoming issues, I’d like to explore fall frosts, as a few regions have already experienced their first, and will revisit the topic of folklore and what it might tell us about the upcoming winter.

If you have questions about either topic, I’d be glad to hear from you. Feel free to email me: [email protected]. I’d love to hear from you about these or any other weather topics you’d like me to cover.