Prime growing conditions in southern Alberta and better corn genetics have been a game changer for feed in the cattle industry as it looks to lower its dependence on the United States amid trade uncertainty.

TFS Expanse has been growing Syngenta’s Enogen corn for years and operates four feedlots in Alberta, averaging about 30,000 head of beef cattle a year for custom feeding.

WHY IT MATTERS: Increased corn acreage in southern Alberta aids feed industry and inputs for cattle for ranchers looking closer to home in Canada.

Read Also

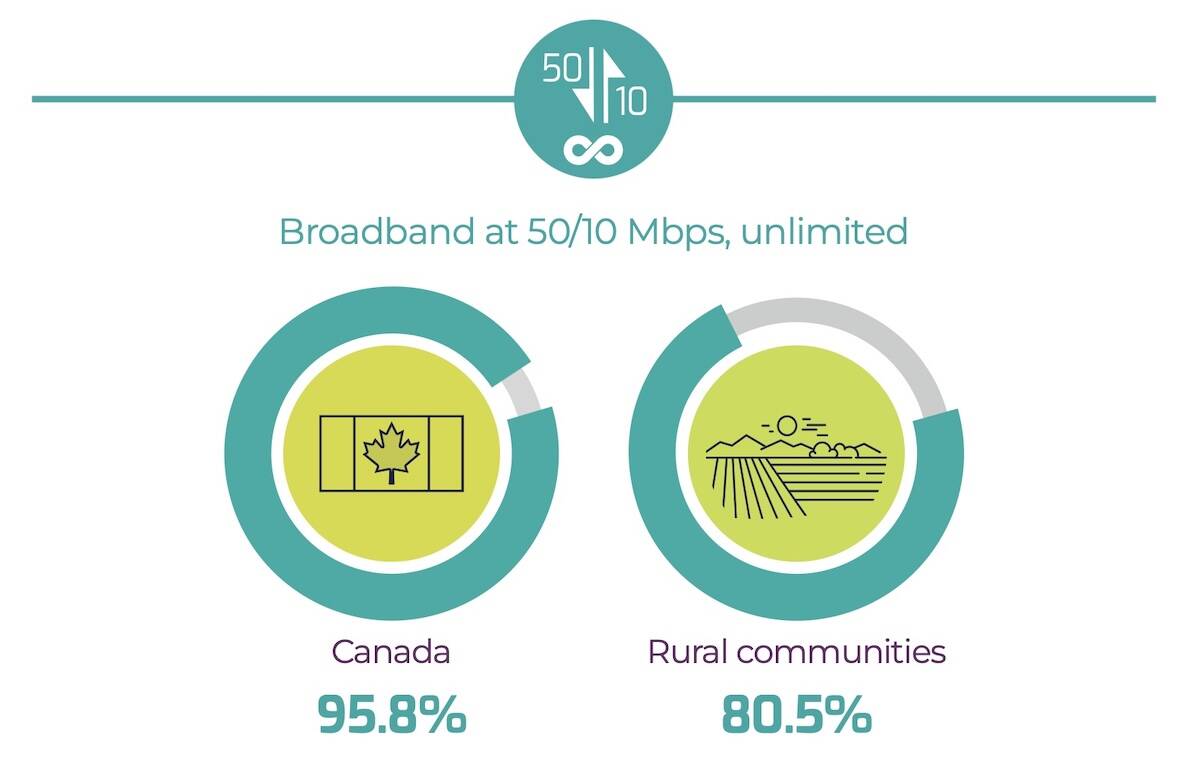

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

The variety was originally developed for the ethanol industry and contains an alpha amylase enzyme, which enhances the breakdown of starch in the cattle’s rumen, which provides for higher feed efficiency and better nutritional value.

TFS Expanse has been shifting to a wet-corn program for the past year and a half as part of an emerging trend in the region.

“It has great growth potential. If every feedlot did 10,000 tonnes of it, it would make a huge difference in the amount of corn that we have to import from the U.S.,” said David Bekkering, co-owner and farm manager of TFS Expanse/Feedlots.

He said shorter shipping distances have also had environmental benefits.

Alberta silage and grain corn acres have increased to 300,000 from 40,000 since 2014.

Corn yields are also increasing.

While they were averaging 150 bushels per acre 15 years ago, TFS has been seeing average yields of 250 bu. per acre in a very strong year, which dwarfs barley.

The company uses Enogen corn for two-thirds of its wet-corn program, which used more than 17,000 tonnes in 2025.

Bekkering said one acre of corn can feed approximately 2.5 animals.

“They had a pretty good year with barley around here with irrigation, about 100 to 120 bu. on average. Relatively speaking, they’re getting about two to 2.5 tonnes of barley per acre. So we’re basically doubling the number of animals we can feed (on corn) per acre of land use,” he said.

Financial benefits

Cows can also graze the stover after the corn has been harvested. With the crop off in November, that means five months worth of food supply going into March.

“It’s almost like a winter grazing. That reduces our costs greatly on the cow-calf side of things. You are able to feed those cows almost for free on the stover,” said Bekkering.

Steam flake corn is the gold standard for feed digestibility with livestock, which TFS Expanse has reached since the early 2000s, along with a handful of other producers in southern Alberta.

However, Enogen has been closing the gap in the nutritional differences. The wet-corn process saves money overall economically but does require specific storage management practices.

“With steam flake corn, you have to expend a lot of energy. You have to cook it, bake it and roll it. It’s about $10 a tonne,” said Bekkering.

With two turns of cattle going through the company’s feedyards totalling 60,000 head, that’s a lot of cost savings when moving from steam flake to wet corn.

Mitigating trade uncertainties

Feedgrain is protected by the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement, but there is still plenty of trade uncertainty.

“If all of a sudden China steps in and decides to purchase a lot of soybeans from the U.S., then all of a sudden that might draw more acres into soybeans for next year, which might influence the price of corn because there’s a shortage of corn acres,” he said.

“Because of the uncertainty in trade, it’s probably more of a problem right now than the tariffs themselves.”

The United States exported 651,000 tonnes of corn to Canada in 2022-23, according to the U.S. Grains and BioProducts Council.

Producing feed closer to home has become a greater priority for the industry, considering currency fluctuations, tariff/trade issues with the U.S. and the spectre of potential railway labour disputes.

“We’re hoping to produce more corn locally because we’ve got an abundance of irrigation land here, and corn pay is better than growing a cereal crop on a per acre basis,” said Bekkering.

“Getting better economics by growing corn, we avoid having to buy from the U.S. if needed, which gives us a buffer. We probably will never be able to produce enough corn here to feed everything, but with our combination of western barley and our own local corn, we can go less and less with U.S. corn.”