They come at a time when some question Canada’s emphasis on wheat quality assurance and the registration system

If there is good news in a recent wire service story that told the world some customers are complaining about Canadian wheat that wimped out in the bakery, it’s that complaints over quality are so rare they become news.

Chinese officials complained this past winter, suggesting that a lack of processing consistency in the CWRS class might prompt them to switch to buying Dark Northern Spring (DNS) wheats from the United States, Canadian International Grains Institute (Cigi) executive director Earl Geddes told the Canada Grain Council’s annual meeting April 2 in Winnipeg.

Read Also

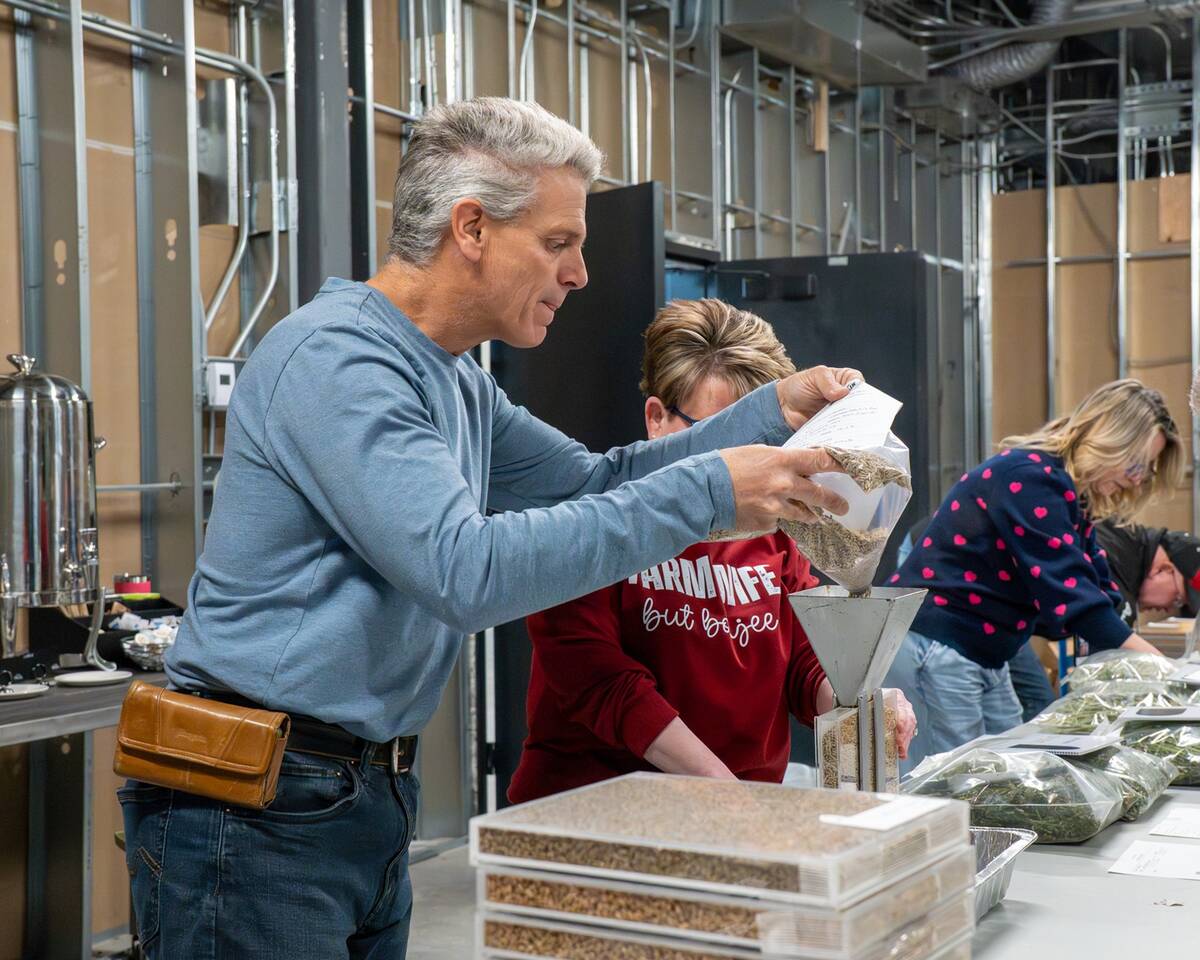

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Geddes said the complaint itself is manageable. The bigger question is how well prepared the industry is to collectively fill the customer service and brand maintenance role once played by the Canadian Wheat Board.

The concerns over Canada Western Red Spring wheat lacking dough strength have come to the forefront just as pressure is increasing from some quarters of the industry to further deregulate the quality control system.

“If we address it properly… I don’t think that this is insurmountable in any way to the point that the Canadian wheat brand will lose its position,” Geddes said, noting that when customers report an issue, it’s often a matter of assisting them with adjustments in the baking processes to get the performance they need.

At the same time, he noted Canadian exporters aren’t accustomed to addressing this side of the wheat-selling business.

Some industry officials say CWRS dough strength has weakened in recent years because some of the most widely grown varieties such as Unity, Lillian and Harvest, have weaker gluten strength. All three have strong agronomic benefits such as midge resistance or higher yields making them popular with farmers and now dominate the CWRS class.

One hypothesis is wetter-than-normal growing conditions the past two growing seasons reduced gluten strength even more. Another is that larger volumes of wheat from specific locations are loaded directly on ships rather than blended at export terminals. As well, protein strength wheat typically becomes stronger in storage and the wheat in question hadn’t been stored for as long as is typical.

“It could be a variety problem, it could be a collection issue — that we’re not collecting the way we used to,” said Elwin Hermanson, chief commissioner of the Canadian Grain Commission. “There are all kinds of things it could be but we need together as an industry to find the right solution — if there is a problem.

“I don’t think there’s an irreparable problem, but I think we’re hearing some concerns expressed that we should take seriously,” Hermanson told reporters at the same meeting.

Bakers want flour that bakes the same every batch. Inconsistency increases cost. Part of the Canadian wheat brand has been consistency.

Some unexplained variability is showing up in this crop year’s CWRS wheat, Canadian National Millers Association president Gordon Harrison said in an interview on the meeting’s sidelines. He said the inconsistency is showing up in water absorption, which affects dough strength.

There are ways to adjust the milling and baking processes to compensate when problems arise, but it’s better if wheat meets the customer’s needs in the first place, Geddes said.

Canada’s reputation for having the best wheat in the world is the result of its variety development and registration system, overseen by the CGC, he said. Farmers and grain companies contribute by delivering varieties to the right class.

“If you want to have that brand image that wheat has… as the best in the world, then you have to work at it and you have to commit to it,” Geddes said.

“The industry needs to decide which markets it wants to be in and which ones make the most sense.”

Some say Canada should focus on medium-quality wheat. Those markets are as far away as those who buy higher-quality milling wheat, Geddes said. When prices are comparable most customers will buy CWRS wheat over DNS.

Canada can capture other wheat markets because of its wheat classes. Each class has a specific end use, Hermanson said. In the new open market, other classes will now get more attention, he added.