Thanks to high cattle prices, many producers may be thinking of investing in a handling system.

The goals may be simple — such as improving efficiency, reducing animal stress or allowing one person to safely process cattle. But what that system looks like is left to the individual producer.

“There is no magical facility that will make cows quiet, make sure they come into the facility calm and quiet,” says Dylan Biggs, who has been giving livestock-handling equipment talks for more than 20 years.

Few operations “start with a clean slate,” he notes, and in many cases the layout of the yard may date back a half-century or more.

Read Also

UCalgary breakthrough may stop canola shatter and boost yields

Research from the University of Calgary on shatter-tolerant canola could save Canadian farmers time and money.

“These systems are far from ideal, but it doesn’t mean they don’t work,” says Biggs, who operates TK Ranch south of Coronation.

“For me, coming from a livestock-handling background, you can get by with a less-than-ideal handling facility if you do a good job handling cows in pastures. The majority of the problems can be addressed in the pasture.”

Whether upgrading or building a new handling system, the biggest factor to keep in mind is flow of the animals, he says.

- More on the Alberta Farmer: Give up the chase – things you need to know about livestock handling

“(The cattle) need to see there is somewhere to go. The worst situations are when the cattle have a little ways to go and they are forced to turn right away when they get into the handling facility. I like straight lines and room to go through or into a facility without change of direction and plenty of space. In addition, try not to have gates too narrow going into facilities.”

The goal should be to have cattle move steadily through the system with as little intervention from the handler as possible.

“From a livestock standpoint it’s easier on cattle if there is good flow and then you aren’t fighting them,” says Biggs. “The setup needs to be logical for cattle to perceive where and why to go.”

And cow logic is different than the human variety, he notes.

“We are linear in thinking, (but) when cattle flow in a system they get to a point where their natural desire is to exit where they came in,” he says. “Capitalize on that natural want.”

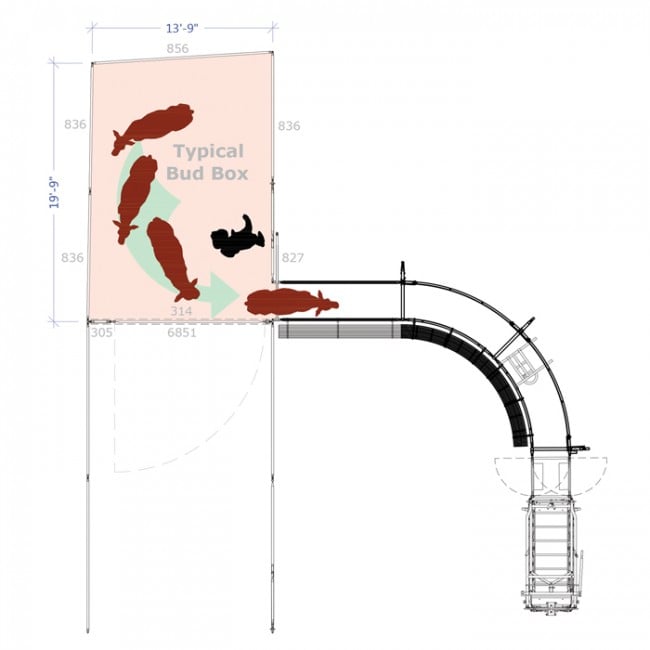

This is the principle behind the Bud Box, created by low-stress livestock-handling expert Bud Williams. The box is a small rectangular enclosure where the exit (just wide enough for one animal) is right beside and perpendicular to the wide entry gate. After closing the gate, the handler moves just past the exit. While she’s doing this, cattle reach the end of the box, naturally turn back towards the entrance, and then readily move through the exit.

“By setting up sorting and facilitate flow into scales and crowd tubs, have them go by and go back in that same direction,” says Biggs.

The dynamic is quite different when cattle are forced towards dead ends and through narrow alleyways, he says.

“So when the cattle decide to come by (you) and come down the alley they are running. If one runs they all run. We force ourselves into their flight zone and think we are doing good.”

Some producers don’t like to use a chute when treating animals, arguing it quickly makes them “chute sour.”

But it’s not the facilities that are to blame.

“Gates, corrals, chutes, scales, crossing highways or bridges, trailers — they can sour on anything,” says Biggs.

The real problem is how they’re being handled. The most common mistake is pushing harder just as the animal is entering a chute, trailer, or gate.

“Typically, without thinking, the closer we get to where we want the cows to go, the harder we push,” says Biggs. “We end up pressuring the cattle more where we want them to be and sour them.

“We want the cattle to come into the chute calm and quiet. Then you can let them out and bring them back, no problem. It’s not what happens in the chute, it’s all the commotion leading up to the chute.”

He likes to “train” cattle by allowing them to move through a new or modified system without working them. Many producers say they don’t have time to do that, but Biggs considers it an investment that pays major dividends.

“The more the cattle are handled, the easier they are to handle,” he says. “Don’t traumatize them, (and) they will come in over and over again. Sour cattle come from improper handling — if your cattle trust you, they will go in.”

There are many options when upgrading a handling system or building a new one, but the system is just a small piece of the equation.

“I had the opportunity to work in new engineered facilities, but that doesn’t make it any easier,” says Biggs. “People don’t intentionally make their cows wild, but they need to make sure they come into the facility calm and quiet.”