Western Canada is on an “inevitable” march towards hot, dry summers and mild winters that will make southern Alberta feel like northern Texas, according to a new climate change mapping program.

“One of the big, striking conclusions of the atlas is that, even if we reduce emissions, we still see substantial changes to our climate,” said Ryan Smith, lead researcher on the Prairie Climate Atlas project.

The online atlas is “the first big product” from the Prairie Climate Centre, a collaboration of the University of Winnipeg and the International Institute for Sustainable Development that regionalizes climate change information for Western Canada.

“People don’t think that climate change affects them unless they see it happening to their community,” said Smith. “Up until now, most of the climate change information that people have received is very, very general. This is the first time we’ve really drilled into the details to get not just region specific but rural municipalities. We’re getting really specific information out of the climate models.”

Read Also

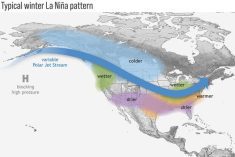

Winterkill threat minimal for Northern Hemisphere crops

The recent cold snap in North America has raised the possibility of winterkill damage in the U.S. Hard Red Winter and Soft Red Winter growing regions.

Using a series of interactive maps and graphs, the atlas shows how Western Canada’s climate could change over the next six decades in a ‘high-carbon future,’ where it’s basically “business as usual,” and in a ‘low-carbon future,’ where “immediate and drastic steps” have been taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- Read more: How to use the Prairie Climate Atlas

Users can look at where their communities, rural municipalities, and eco-zones sit today in terms of the number of days above and below 30 C, seasonal precipitation, and frost-free periods. Users can then see how those numbers will change in the near future (2021 to 2050) and in the far future (2051 to 2080.)

Drought implications

And the numbers are pretty startling.

“For Lethbridge right now, in an average year you’d get between 16 and 17 days that hit 30 C or warmer. That’s just over two weeks of +30 C days per year,” said Smith.

“When you step forward into that high-carbon far-future scenario — basically, where we keep doing what we’re doing — that number goes to about 54 days. That’s just shy of two months of +30 C weather.

“Fifty-four days is similar to what they get in northern Texas.”

In the low-carbon scenario, Lethbridge will go from 16 days above +30 C to about 38 days, he added. And Albertans can expect to see those increases even as they move north.

“Edmonton gets three days of +30 C weather, but if you were to go to that far-future high-carbon scenario, you’re up to 22 days, or three weeks. In the low-carbon scenario, you’re up to 12 days,” said Smith.

“You’re still quadrupling, even under the low-carbon scenario. It’s a huge increase, and it’s a huge concern.”

While the models project wetter winters and springs — which could result in more flash floods like the ones seen in Calgary and High River in 2013 — “the big concern is what the climate models say about summer precipitation,” said Smith.

“In Lethbridge County, they get about 140 millimetres in an average summer in terms of rainfall. That’s going to go down to 130 millimetres in the far future,” he said.

“That’s only 10 millimetres — it’s not a huge decrease — but any decrease when the temperatures are going up and up and up rapidly is very concerning. Evapotranspiration is directly related to the temperature.

“If you have a doubling in the temperature, evapotranspiration might double along with it, and if precipitation doesn’t keep pace, that could lead to huge drought implications.”

Adaptation

But there are a few things that can be done to reduce some of the effects of climate change, no matter how “inevitable” it may seem, said Smith.

“The agricultural sector puts out a lot of nitrous oxide emissions, which come from the application of fertilizer. That is a greenhouse gas that is 298 times more potent than carbon dioxide,” said Smith.

“There are huge opportunities if you can reduce fertilizer load and reduce carbon emissions. That will help mitigate the problem.”

But adaptation is really “the bigger picture,” he said.

“We really have to adapt to these changes, not just wait for that miracle technology,” said Smith. “Even if that technology comes around, changes are still going to happen.”

For instance, producers will need to adjust their crop rotations as the shifts in temperature become more drastic, he said.

“Canola is a staple crop, and when the temperature hits 30 C, canola suffers. It can barely withstand those kinds of temperatures. So basically, say goodbye to canola,” said Smith.

“It’s a similar sort of thing with wheat. Yields can fall off very, very quickly once the temperature climbs much above 30 C.

“So does this mean more corn and more soybean — basically those crops that are grown farther south that love the heat?”

Water storage systems will also become more important as the climate changes, he said.

“We need to find ways to store water when we have an excess of it so we can use it when we have not enough.”

Healthy soils

But one of the best ways to prepare for these future changes is to build healthy soils now, said Smith.

“Building up soil organic carbon is one of the best ways to hold on to moisture,” he said.

“Different tillage strategies and planting strategies that prevent erosion are all things that contribute to keeping the soil healthy.”

Nora Paulovich, manager of the North Peace Applied Research Association, agrees.

“I believe healthier soils will result in more resiliency,” said Paulovich. “There’s so many benefits from having healthier soils that they’ll definitely become more resilient.”

And if temperatures continue to increase, producers could be in “dire straits” if their soils aren’t healthy, she said.

“Moisture is always our limiting factor,” said Paulovich. “So if there’s any way that we can improve the health of our soils, that will improve the ability of our soils to retain water and improve infiltration so that the water we do have is there for the plants to use when a drought does hit.

“If we can increase our soil organic matter from even one per cent to three per cent, that will double the water-holding capacity of our soils.”

But it will take some changes to current production practices, she said.

The first change is moving to zero or low tillage if you haven’t already.

“The less tillage the better,” said Paulovich. “We have come very far in that in the last 15 years. Many producers have adopted zero to minimum till, and that really has helped minimize water and wind erosion.”

Plant diversity is also “a must.”

“Even though many producers have adopted minimum till, they’re still sowing monocultures,” she said.

“We’ve been growing monocultures way too long, and we absolutely have to be introducing diversity.

And producers should be keeping the soils covered for as long into the growing season as possible.

“We do need armour on the soil,” she said. “By having the soil covered, that minimizes the effect of the hot sun. If you take a soil temperature where there’s good soil armour, it’s definitely lower than where there’s bare soil.”

“All those soil conservation strategies work, but we probably need to be a little more diligent about using those strategies in the future,” added Smith.

By making some of these small changes, producers will be better able to “adapt and plan for climate change,” he said.

“It’s not all doom and gloom. Let’s not give up. Let’s reduce emissions, but let’s also plan for it. If we do it smartly, we should be OK.”