How expensive is Alberta farmland? Try double what it was just five years ago.

“Over the last five years, we’ve seen cash farm receipts going up across the country and especially in Alberta,” said Joel Bokenfohr, manager of business structures and financial policy with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

“We have a strong farm economy where a farm’s investment decisions are now going into purchasing assets — land being the obvious choice.

“That’s really driven up farm values.”

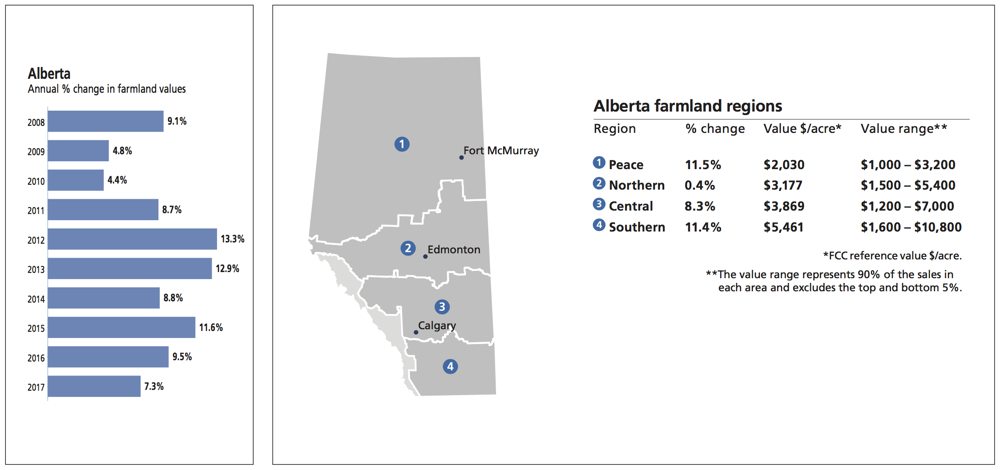

Farm Credit Canada’s latest report on farmland prices pegs the average increase in Alberta at 7.3 per cent. While less than in 2016 (9.5 per cent) or 2015 (11.6 per cent), the power of compounding amplifies the price increases.

Read Also

‘Millions will die’: Foodgrains Bank faces $2.7B federal funding threat

Foodgrains Bank warns $2.7B aid cut triggers a humanitarian crisis, risking global hunger relief and 40 per cent of its funding.

But it all comes back to increased profitability, said Bokenfohr.

“The vast majority of our farms are in good financial shape,” he said. “We’ve seen farm cash receipts continue to increase year after year.”

Some buyers may also have been motivated by the belief that the era of extremely low interest rates is ending and the past year was a good time to lock in. But their crystal balls are also predicting the investment will pay off.

“Each farm is making investment decisions based on the signals they get from the market,” said Bokenfohr. “And right now, farmers are seeing signals that we have relatively good international markets to service, and they’re investing in land purchases based on that.”

The biggest farmland value increases were in the Peace Country (11.5 per cent) and in southern Alberta (11.4 per cent). Central Alberta also saw a significant jump, at 8.3 per cent, while the north-central area — a broad cross-province band including Edmonton — saw the lowest rise, at 0.4 per cent.

Those regional differences are a reflection of supply and demand in the different parts of the province, said Dave Weber, a valuations and agrology specialist at Edmonton-based consulting company Serecon.

“A lot of people are looking to buy more land and expand their operations, but it’s becoming harder for farmers to buy land because of the price,” said Weber.

“Some markets can be very localized, so if you get a lot of active buyers in a certain area, the price can be a lot different than other areas.”

Raising eyebrows

That disparity in prices can be seen across the country.

Alberta saw the fifth-highest increase among all the provinces, with Saskatchewan topping out at 10.2 per cent, Nova Scotia in a close second at 9.5 per cent, Ontario just behind at 9.4 per cent, and Quebec trailing at 8.2 per cent.

British Columbia saw the lowest increase, at 2.7 per cent, while Manitoba (5.0 per cent), Prince Edward Island (5.6 per cent), and New Brunswick (5.8 per cent) remained at the middle of the pack. (Newfoundland didn’t have enough purchase information to report a value.)

Still, the national increase of 8.4 per cent is double what J.P. Gervais, FCC’s chief agricultural economist, predicted a year ago.

“The fact that we recorded an average in 2017 (in Canada) that was greater than the year before may raise a few eyebrows,” Gervais said. “Some could even ask if this is the beginning of a new trend. I would say no to that.

“I think it’s rather a sign of a stable and strong farm economy. That means that Canadian farms are generally in a strong financial position when it comes to net cash income and balance sheets.”

The story is much different in the United States, where land prices aren’t even keeping up with inflation. While Canadian values have shot up 26.4 per cent over the past three years, land values in the U.S. have gone up only 4.4 per cent during that same period.

“Although Canada is often expected to follow trends in the U.S., we haven’t experienced the impact on land values that has happened in the U.S.,” said Weber.

That’s because U.S. farmers are working in a different economic environment than their Canadian counterparts, Bokenfohr added.

“We’ve seen higher farm returns, particularly on products like canola, so we’ve been able to achieve farm returns that they haven’t seen in the States. They’ve been on a bit of a decline,” he said.

That’s an understatement — net farm incomes in the U.S. have plunged by 50 per cent since 2013 due to lower crops prices. In comparison, Canadian farm cash receipts were up eight per cent in 2017 versus the previous five-year average, Gervais said. Crop receipts rose 1.5 per cent to hit a record high last year, he said.

Canada’s weaker dollar was the biggest difference, he added.

Risk to expansion

Even so, don’t get carried away, Gervais warned.

“No matter what type of operation, or where you happen to be, it’s always a good idea to have a risk management plan,” he said. “You have to review it on a regular basis and then protect yourself or your operation against unforeseen circumstances or events.”

Gervais is (once again) expecting farmland prices to cool off in 2018, but still increase despite a small rise in interest rates and trade uncertainty (both from NAFTA negotiations and a possible trade war between the U.S. and China).

His forecast also assumes the Canadian dollar will stay below 80 cents U.S.

“Despite all the uncertainty and volatility I want to emphasize that (Canadian) farm income is still projected to grow (in 2018) and I think it’s critical to be able to sustain land values into the future,” he said.

Over time land prices should increase by the rate of inflation and increased productivity, which these days is about two per cent a year for each, Gervais said.

That’s good for farmers who already own land, they’re less positive for newcomers or those hoping to expand.

“There’s a risk that farming could become out of reach, especially for the smaller farmers and the younger farmers who haven’t necessarily got themselves established in the market,” said Weber.

“It makes it more difficult for them to get their foot in the door.”

Even established farmers with plenty of equity are challenged, he added.

“As your margins get narrower, you need to farm more acres to put the same money in your pocket at the end of the year in order to make a living,” said Weber.

“It’s becoming more difficult to buy the land and make a living off of farming it.”

For most farmers, that’s the catch-22 — they need to invest in more land to increase revenues, but they also need the increased revenue to service the added debt.

“As land prices increase, their ability to generate revenue is also going to have to increase,” said Bokenfohr.

“There is a risk of putting yourself in a dangerous position by buying too much.”

Producers who have short-term debt on equipment purchases or other loans will need to be a little bit more cautious when looking to purchase more land, he added. That should include some scenario planning: What will happen if interest rates continue to rise? What if the Canadian dollar rises? Or if there’s a decline in crop prices?

“You need to make sure you’re using good business management tools to ensure it’s the right decision for you,” said Bokenfohr.

“There’s no crystal ball for any farm that’s buying land, so I would encourage them to do some scenario planning.

“As long as you can service the debt and do good scenario planning, things look relatively positive.” — With files from Allan Dawson