A visit to any local equine tack shop will showcase a striking array of tack and accessory tack available to place upon the head of a horse with the promise of improving horsemanship, fashion or a horse’s performance.

Many of these devices are potent tools that have the ability to leverage and compound tensile forces onto the sensitive parts of the horse’s head to effect head position and control the horse. This includes halters, bridles (both bitted and bitless), and the wide selection of rein setups such as draw reins, side reins, martingales, tie-downs, and chambones. This category also includes restrictive devices such as nosebands, crank nosebands, cavessons, and flashes.

Read Also

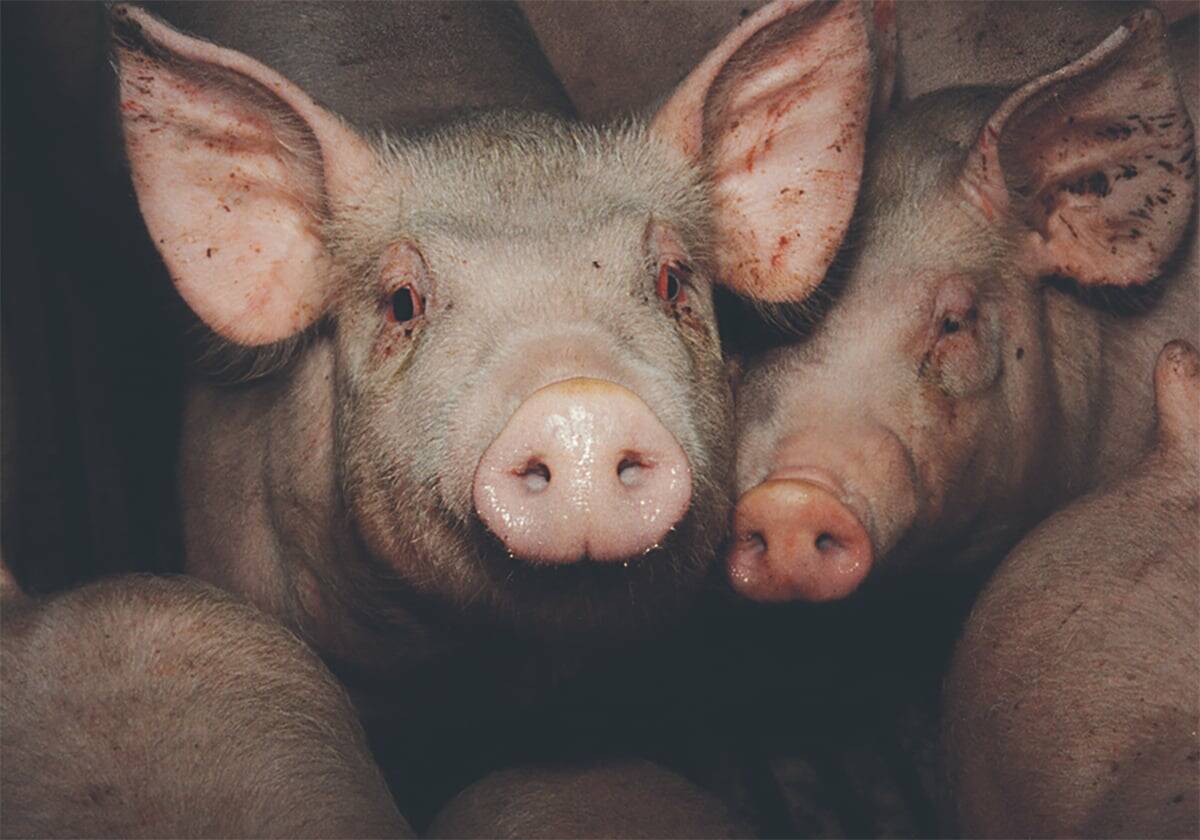

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

Unfortunately the human’s angst about and fixation upon achieving the ‘desirable arched’ headset or neck flexion in horses can come at the expense of forcing head and neck frames, unnatural headsets, unbalanced horses and ultimately leads to structural unsoundness, poor athletics and troubled horses.

The contrivance of the horse’s head and neck into a particular frame or ‘headset’ through the use of tack, pressure, and training is physiologically and psychologically problematic for the horse. It invites strains and tensions to the horse’s body and sets the stage for behavioural conflict, musculoskeletal injuries, compensation patterns, pain and physically interferes with the horse’s own abilities to carry itself properly in posture and carriage. This understanding is the same for every horse, regardless of breed or discipline.

Whenever rein work in the horse is ‘overmanaged’ and based on a weighted pull, holding, restraining or otherwise forcing the horse’s head into a set and fixed position, a confrontation of tensions occurs between the handler or rider and the horse.

This confrontation initiates a physiological reflex which causes the horse to brace its neck muscles and ‘break’ its upper neck in between the second and third cervical vertebrae rather than release at the poll.

This anatomical location in the horse’s neck is particularly vulnerable to the forces of leverage, pressure and restriction that can be applied through a number of rein step-ups and restrictive nosebands. These devices can override the horse’s own inclination to appropriately place its head and neck and maintain its own balance.

Yet the resulting ‘false’ flexion at the third neck joint creates a neuromuscular fault line in the proper functioning of the spinal column of the horse. Subsequently horses trained in this frame develop muscles along the top of their neck and over time the shape of the neck will appear ‘upside down’ or ‘elk-like.’

The ‘braciness’ and tension within the horse handled this way will improperly load and burden the forelimbs placing the horse at a greater risk for lameness and hoof imbalances.

The unnatural head- and neck-set triggers a sympathetic reflex in the muscles along the topline and causes the back to become more and more hollow over time.

Horses that carry tension along their topline will short stride with their hind limbs, and their hindquarters will appear to trail out behind them. The biomechanical faults created in the horse’s body when flexion of the neck is misappropriated denies the horse the elasticity and ‘springiness’ of a properly balanced musculoskeletal system and aligned joints.

Horses that are allowed the action of properly releasing at the poll joint (base of the skull and first vertebra) will reflexly turn off unnecessary bracing and contraction of the upper neck muscles.

This then allows the horse to activate the muscles that lift the root of the neck and thus develop the muscles at the base of the neck that can arch and telescope the neck. It also allows the horse to engage the hindquarters, coil the loins and round the back efficiently and comfortably creating lightness, elasticity and the ease of movement in the horse’s body necessary for sound athleticism.

Many horses struggle with what we are asking them to do with their head and neck because it defies the natural laws that their bodies and minds abide to. This creates an emotional angst that remains within the horse and manifests as behavioural problems, an unwilling attitude to work and ultimately results in physical unsoundness.

Horses worked into a forced head and neck position will typically demonstrate their discomfort and distress in their facial expression through ‘grimacing’… ears stiffly tilted backwards, tightening of the orbits (eyes become almond shaped), the jaw muscles and lower chin tighten and wrinkles develop around the eyes and nostrils.

These indications of tension in the face are also indications of tensions elsewhere in the horse’s body.

In the proper sequence of events for movement of the horse’s body the horse uses its head and neck as a cantilever to balance its body. It defies natural laws to impose a head and neck setup upon a horse expecting the horse’s body to follow in balanced athleticism or self-carriage.

The way a horse needs to carry its head and neck for optimum balance at any point in time depends upon and reflects the horse’s constitution and its level of understanding and conditioning.

When and if the horse is asked to carry a rider, the horse will also need to factor into the equation for its balance the specific issues created by that rider’s own balance, level of awareness and skill and the rider’s level of sensitivity, feel and intention.