Glacier FarmMedia – Increased demand driven by the biofuels market will put upward pressure on canola prices.

The biofuels industry could drive canola demand into uncharted territory in the coming decade, says one industry expert.

“The capacity of crush could grow from 11.3 million metric tonnes today to 18 million metric tonnes in three or four years,” said Chris Vervaet, executive director of the Canadian Oilseed Processors Association.

Read Also

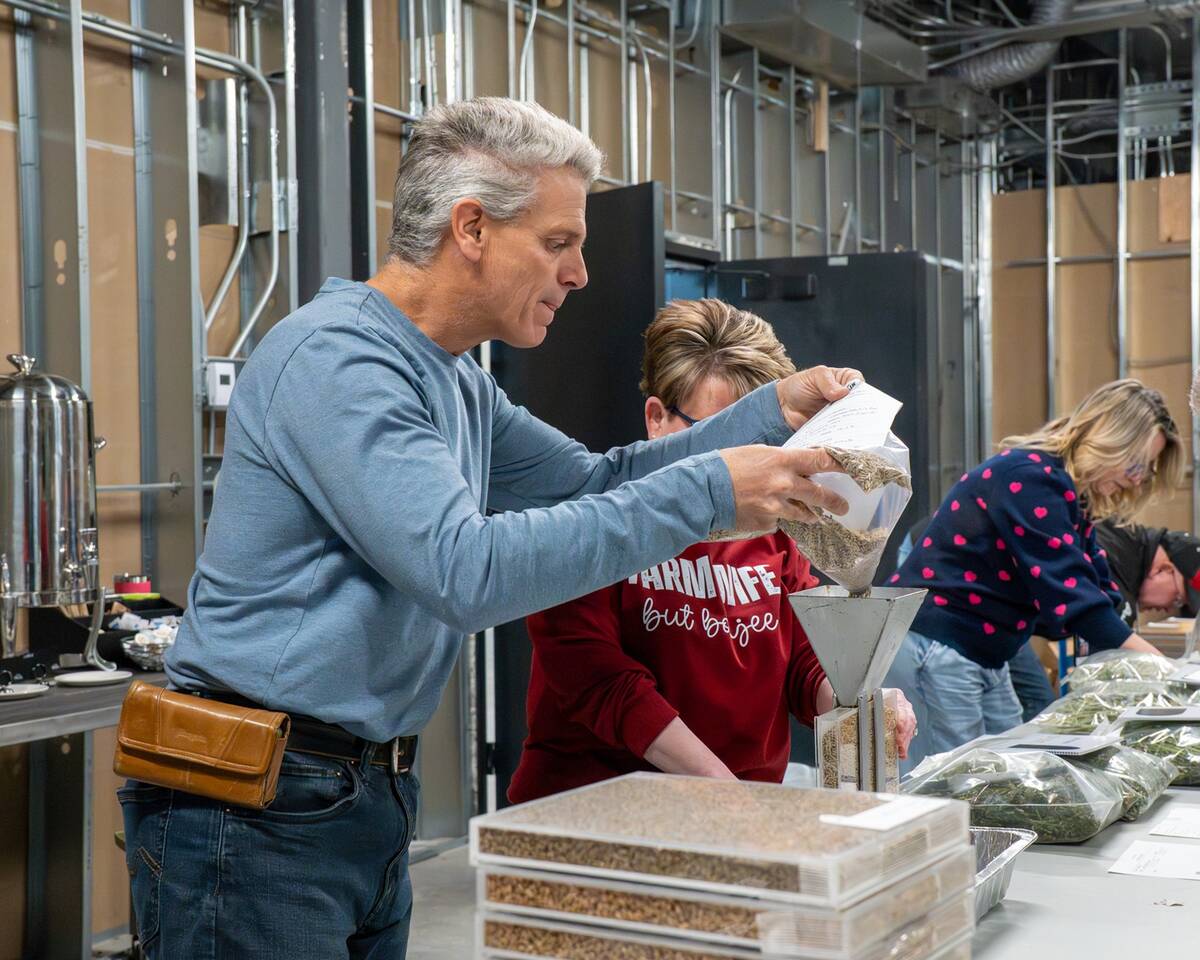

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Vervaet was among the speakers at this year’s CropConnect conference in Winnipeg Feb. 14. His talk focused on the impact of renewable fuels on the canola value chain.

“This is unprecedented. I’ve talked to folks who have been around oilseed processing for the better part of 30 or 40 years. They’ve never seen this kind of growth.”

Roughly 2.5 million tonnes of canola seed equivalent stocks are now used for biofuel markets in Canada, the U.S. and the European Union. Vervaet said it could grow to five million tonnes by 2026 and as high as eight million tonnes by 2030.

“We’re taking a stab in the dark here a bit, but we feel pretty optimistic about the role of biofuels in seed demand going forward,” he said.

To meet that demand, seven new Canadian facilities have been announced over the last three years to bolster renewable diesel production capacity.

“If it all gets built the way that it’s been described in their press releases, that could be four billion litres of capacity over the next four or five years,” said Vervaet.

South of the U.S.-Canada border, another 25 facilities are either operating, under construction or planned.

“If that all comes to fruition in a couple of years time, that’s close to 30 billion litres of production capacity,” said Vervaet. “This is a tremendous opportunity to see more value-added processing occur in Canada.”

Old biofuel, new biofuel

Renewable fuels are derived from biological, easily replaced sources like canola, corn, wheat or other forms of biomass, and have gained attention based on their promise for lower carbon intensity compared to fossil fuels.

Corn-derived ethanol is one example, and has been used as a fuel additive for decades. Biodiesel produced from canola, soy, tallow or used cooking oil is a more recent example. It’s been used for the past 15 or 20 years.

“They’re low-carbon essentially because of photosynthesis, the natural act of a plant taking carbon out of the air and converting it into energy,” said Vervaet. “Canola, for example, can actually have a carbon footprint that is 90 per cent lower compared to conventional diesel.”

Renewable fuel markets have gained attention in recent months through discussion about new fuel standards in the U.S. and hot debate over fossil fuel alternatives.

Biodiesel has been limited because it must be mixed at 20 per cent with fossil fuel. Sustainable aviation fuel, which has drawn particular attention from oilseed sectors, is also mixed, but at a one-to-one basis with fossil fuel.

Renewable diesel, with canola as a potential feedstock, is the new kid on the block.

“Renewable diesel is produced in a way that is very similar to how a traditional oil and gas refinery produces conventional fossil diesel,” Vervaet said, and the finished product is indistinguishable from fossil diesel.

“So, if you’ve got a tractor that’s running on conventional fossil diesel and you’re looking to replace it with a renewable source, you can run that tractor on 100 per cent renewable diesel. It is a proven and viable solution to decarbonize transportation fuels. And it’s really becoming an important piece of policy development in terms of biofuel programs in both Canada and the United States.”

By the book

The U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard is driving the growth of renewable fuels. For more than a decade, it has mandated the amount of renewable fuel that must be incorporated into traditional fossil fuels. A new program that finalized the mixing percentages for 2023-25 was announced in June of last year.

Canada took longer to introduce similar programming, but in July 2023 it introduced the Clean Fuel Regulation. It differs from the American standard, Vervaet said.

“It still uses a mandate, but it’s not a mandate where you have to blend ‘x’ per cent. It’s a mandate where you need to reduce the carbon intensity of the fuels.”

Carbon intensity is defined as the emissions given off by producing something, divided by the volumes resulting from that production. It is expressed in emissions per unit of output.

These policies led to creation of carbon credit markets in the U.S. and Canada to encourage development of renewable fuels, although prices have proven volatile.

“It’s all about debits and credits,” Vervaet said. “Lower-carbon fuels are the ones that are earning those credits. This is what everybody is chasing these days: getting those credits, because there’s money to be made.”

Oil and gas companies are also trying to pivot business models, hence the number of renewable fuel refineries in the works or recently opened.

“Previously, you would never see this type of investment from the oil and gas industry,” Vervaet said. “They just didn’t support biofuels. It wasn’t part of their business model. They saw it as competition.”

He used a hypothetical example based on California’s carbon credit market, in a scenario involving used cooking oil (UCO), the feedstock lowest in carbon intensity.

“A biofuel producer that is making a billion litres of renewable diesel a year can earn almost $250 million in credits,” he said. “If they can’t get their hands on UCO, well, then they’re going to try animal fat, and if they can’t get their hands on that, they’re going to be looking at canola, and so on.”

What does it mean for farmers?

“At a high level, more demand equals better prices, so that law of economics applies,” said Vervaet. “But as far as farmers getting premiums by participating in these types of programs, I can’t speak to anything specifically.”

That could change with rising demand, he noted. Buyers might introduce premiums as an incentive for producers.

Projections show that the demand for North American canola could rise to 29 million tonnes by 2030. That is up from current demand of 20 million tonnes, 90 per cent of which comes from Canada.

Canola acres are more or less tapped out, industry experts say, so extra production will have to come from increases in yield. In the U.S., however, there may be opportunity for canola acreage to expand.

“If we can continue to grow more canola and see more of our canola go into biofuels, it doesn’t mean that we’re turning our backs on our traditional markets,” said Vervaet. “We’ll still very much be centred on satisfying those demands.”

– Don Norman is a reporter with the Manitoba Co-operator.