It seems like every part of your average farm is generating data these days — but your average farmers still don’t know what to do with it all.

“The more data we have, the harder it is to figure out what to do with it,” said Simon Knutson, agriculture technology faculty instructor at Olds College. “The technology has advanced a lot more over the past few years, but we’re still leaving the majority of users behind.”

The tech in the hardware is continuously being improved — whether it’s in drones using near-infrared sensors to monitor crops, probes and sensors in fields, yield mapping or variable-rate functions on equipment.

Read Also

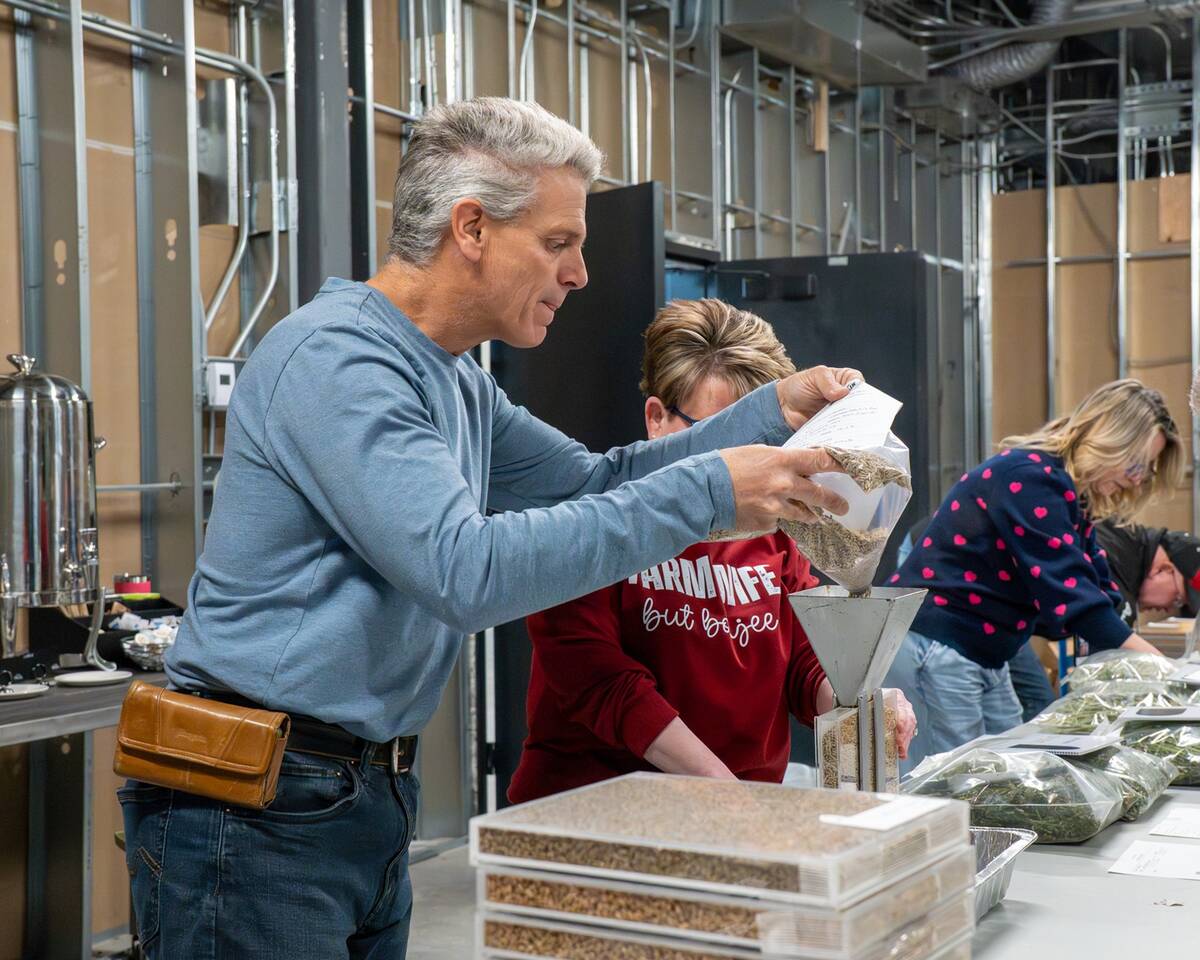

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

At the heart of all of this is data — all of these tools generate reams of it, but most farmers aren’t making the most of the information being collected on their operations, said Knutson.

“I think there are a lot of farms out there that are still not doing some of the basics,” he said. “As an example, every fairly modern combine that’s out there probably has a yield monitor, but the majority of farms still don’t really do anything with that data.”

And the gap between the basics of data management and analytics and what the technology can do keeps widening.

“A lot of the fancy new technology just skips right over the basics, and the majority of farms are not there yet,” said Knutson. “It’s very intimidating for somebody who hasn’t done a whole lot of this. Suddenly you’re seeing all of this advertising and going to trade shows where they have all the fancy tools, and that can be fairly intimidating.

“We need to take several steps down the ladder and get some of these farms onto the first rung.”

Part of the challenge with that, he said, is that these different platforms and technologies aren’t yet fully integrated — though that continues to improve as these tools become more mainstream.

“We have seen a lot of the new platforms and technologies that are coming out are integrating with other platforms,” said Knutson. “I still don’t think we’re there yet, but it has definitely improved over the past two or three years. We have seen advances there.”

But generally, the rapid advances in technology just makes it harder and harder to catch up.

“It seems like the wall is getting higher and higher because things are advancing so much,” he said. “Sometimes we’re still putting the cart in front of the horse. We are at risk right now of isolating or alienating anybody who didn’t get on board with this five or 10 years ago.

“Somebody just needs to help them get going and get value out of the data they probably already have.”

Making it useful

“The focus for us over the last few years has been on mapping different soil properties in the field,” said Knutson. “There are so many potential variables that could influence yields and that we could potentially manage, but that doesn’t mean that they actually relate to anything individually.

“The HyperLayer project is looking at how we can work with all these different data layers to make sense of them and see if we can try to identify how we can use all of this data to make decisions.”

That’s the trickiest part of data and analytics, he said, adding that machine learning and modelling can help with that.

“The more layers you have, the more difficult it is to interpret it,” he said. “I have so much data I could give to the students, but the majority of that data is extremely complex to try and make use out of it when we’ve got multiple layers.

“Just having the data is one thing. Actually understanding it and being able to use it to make decisions is another thing altogether. So the challenge will be for the students to actually turn the data into something useful.”

Once they’ve had some training, students are comfortable merging two or three different data layers to make use of the information they provide. But they soon get to a point where things get complicated fast, he said.

“When I asked the students before they started what they thought they’d be doing, they said, ‘We’ll be taking all these different layers and making maps out of them,’” said Knutson.

“I asked them afterward what they think of that now, and they said, ‘It’s too complicated. We can’t take 20 different layers and do really anything with them because the data is all telling us different things.’

“It’s really changed their mindsets on what they thought precision agriculture is versus what it actually is.”

That’s been a key challenge with some of these new technologies, he added — balancing the expectations about how they’ll perform with the reality of how they actually perform in practice.

“It’s kind of like when you watch “CSI” (Crime Scene Investigation, the popular TV franchise) — they click a couple of buttons and all of a sudden they’re looking at the answer,” he said. “That doesn’t happen in the real world, but I think a lot of farmers think that way as well.

“They think we have all this technology — they should just be able to click a few buttons and it’s done. But we’re still not there, and probably not going to be for most of our lifetimes.”

As such, it’s important for producers to have a “really clear picture” of what they hope to achieve from any new technology they bring onto the farm.

“There’s been a lot of instances where people just run out and buy something without really knowing what it is that they’re looking to get out of it,” said Knutson.

“You really need to have a plan with where you want to go. Just going out and buying a drone or signing up for one of these platforms is all great — as long as you have a justification for it. You need to know what you are actually looking to get out of it at the end of the day.

“I think sometimes people skip over that because they see something new and shiny and just want to get into it.”