Nutrient management is a challenge even in average years — but a million unharvested acres mean this year will be far from average.

Step one is determining available nutrients.

In a cereal crop, the vast majority of the nitrogen, phosphorus and sulphur and about one-fifth of the potassium taken in by the plant are contained in the grain rather than the straw. Wheat requires 2.2 pounds of nitrogen per bushel, which means a 50-bushel crop contains a total of 110 pounds of nitrogen.

In a normal year, approximately 75 of these pounds would be removed in the grain, leaving about 35 pounds to be recycled back into the field through residue. If the crop is not removed from the field, however, expect all of its nitrogen, less about 10 per cent for winter loss, to be available for future production.

Read Also

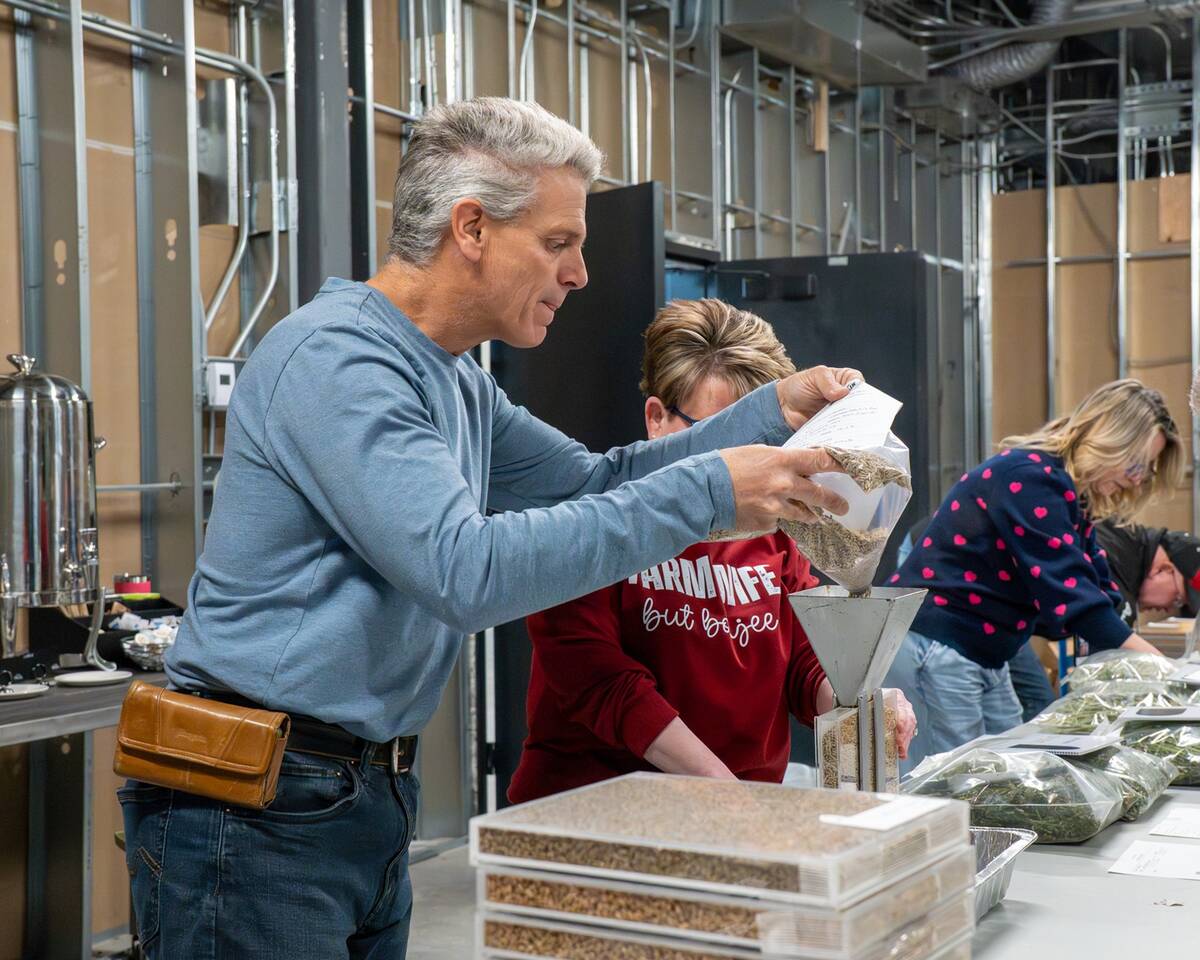

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“If they don’t harvest anything, the previous year’s crop will effectively act like a slow-release fertilizer,” said Tom Jensen, director for North America with the International Plant Nutrition Institute.

Adjusting fertilizer rates to account for increased nutrient recycling is challenging though.

“If a farmer is used to putting on 100 pounds of nitrogen to grow a wheat crop, a lot of them will just use normal rates even though they don’t need to,” said Jensen. “In reality, I think it’s fair to say that farmers in this situation could cut back nitrogen application rates by at least 20 per cent and probably as much as 50 per cent in some cases and still have adequate nitrogen available for the next crop.”

Farmers should also analyze what nutrient application will optimize their crop for the coming year, adjusting application rates according to this year’s unique requirements. Those seeding late may be wise to select shorter-season crops to ensure the plants have enough growing days to reach maturity. Careful nutrient management can also help crops successfully to achieve maturity.

“In a year like this, you really need to be paying attention to phosphorus and nitrogen,” said Mark Cutts, a crop specialist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. “Phosphorus is associated with enhancing maturity in crops. Some producers may be seeding on the late side, so a maturity benefit may be critical. I’d see what the phosphorus recommendation is on a soil test and then stick with it. Definitely don’t underapply.

“With nitrogen, I’d try not to overapply, because it could delay maturity across all crops.”

If wet fields squeeze the seeding window, some farmers may opt for less-than-ideal seeding options to speed the process. Given the choice, most producers apply fertilizer in two bands at seeding: one right alongside the seed and the other a few inches from the seed. Farmers facing a time crunch may opt for the short-term time savings of getting seed into the ground with only partial or even no fertilizer.

“There are options to fertilize after seeding, but none are perfect,” said Cutts. “There is potential to broadcast fertilizer even after the crop has emerged. But if you don’t get precipitation to move it into the soil, a portion of the applied nutrients, especially in the case of nitrogen, could be lost.

“Foliar applications get some nitrogen into a plant but much, much less than the crop requires — typically only a few pounds. Banding at seeding is definitely the best: all other options are compromises.”

Some growers may choose to broadcast both seed and fertilizer.

In broadcasted fields, nitrogen should be incorporated into the soil with a harrow, disk, or other method of disturbance in order to limit nutrient losses to volatilization (gassing off). Because phosphate is not mobile in soil, it should be broadcast at twice the rate one might band.

Though broadcasting seed increases the risk of poor establishment, it does offer certain benefits in addition to speed. Most growers have a maximum amount of fertilizer product they can handle through their seeder. A floater doesn’t have that issue. It might need to pull up to the truck more often but it can apply as much nutrient as a farmer requires, points out Keith Gabert, an agronomy specialist with the Canola Council of Canada.

“If there’s a nutrient you’ve been a bit short of in the past, this might be an opportunity to broadcast it at a higher rate,” he said. “Farmers who are worried about crop left out in the field from last year might not think now is the time to talk about long-term nutrient investment. But if you can look at the big picture, broadcasting provides an opportunity to apply a higher rate of a nutrient like phosphate.”

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, soil test for optimized crop results.

“Producers really need to do them. It’s not the most popular practice but if you have information from a soil test, you can make good decisions,” said Cutts. “That’s return on investment regardless of the crop.”

This article was previously published on AGCanada.com.