The lime works by neutralizing the highly acidic soil preferred by clubroot, reducing the likelihood of spore germination and plant infection

Treating soil with lime could help farmers curtail clubroot infections in canola, new University of Alberta research suggests.

Spot-treating soil with the mineral reduced the overall occurrence and severity of the disease by 35 to 91 per cent, growth experiments showed.

The finding, published in the Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, could give farmers an option for managing clubroot, alongside current use of resistant varieties.

Lime has traditionally been used to manage clubroot in related plants, such as cabbages for market gardens, but not on a large scale in canola crops.

Read Also

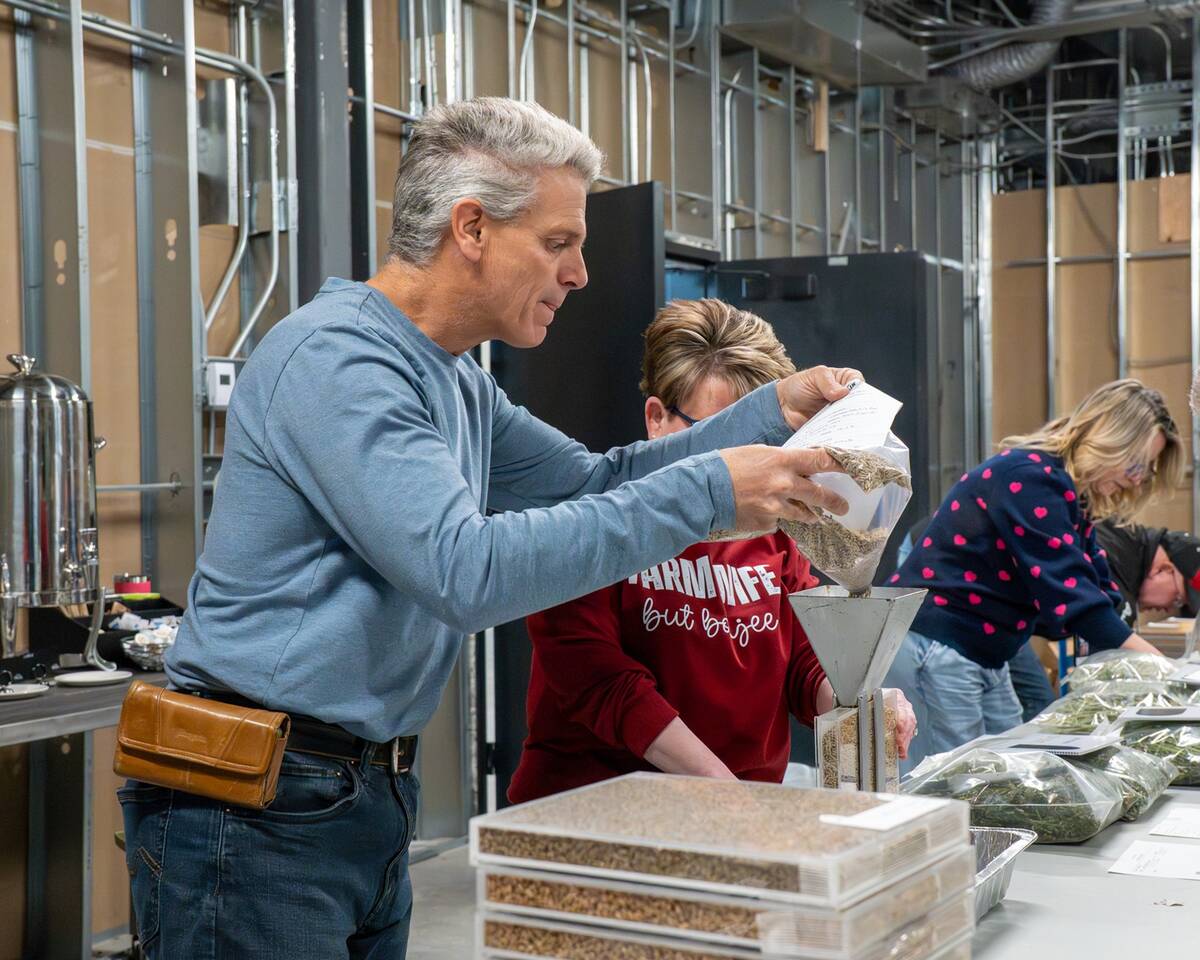

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“Genetics are our first line of defence, but plant resistance can erode or break down, so we need to find every possible option to help control the clubroot pathogen in what is an important cash crop for Canada,” says researcher Nicole Fox.

As a non-genetic management practice, liming treatments could help combat all strains of clubroot in canola, adds Fox, who conducted the study to earn a Master of Science in plant biosystems from the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences.

Spot treatments could help control contaminated areas of a field or stem the spread of clubroot into a new field.

The lime works by neutralizing the highly acidic soil preferred by clubroot, reducing the likelihood of spore germination and plant infection.

One of the first studies to test hydrated lime in the field in Canada, the research also showed the product was more effective at managing clubroot in canola than granulated limestone, another form of lime more commonly used to treat agricultural soil.

Applying moderate to high amounts of the powdered lime resulted in canola plants that were still productive even if infected by clubroot. The plants also released fewer spores of the clubroot pathogen.

Lowering acidity levels also increases the soil’s general health, an important benefit to liming, considering Alberta has about one million acres of strongly acidic and 4.5 million acres of moderately acidic cropland soils, Fox notes.

But hydrated lime’s effectiveness does hinge on certain factors, like the interval between application and seeding, so it needs fine-tuning before it can become a practical tool, says U of A plant pathologist and study co-author Stephen Strelkov, who supervised the research.

“While lime showed good potential for clubroot management, the results varied. Sometimes the treatments provided very good control; other times they didn’t. So, we need further research to work out some details.”

Canola bred to be genetically resistant is still the most effective tool against clubroot, Strelkov adds, but options like hydrated lime could help improve the “durability of resistance and overall sustainability” of disease management.

“There may be situations, if the efficacy of lime is consistent and the costs of application reasonable, that it could be used on a larger scale.”

The research was funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canola Council of Canada, Alberta Canola, SaskCanola and the Manitoba Canola Growers via the Canadian Agricultural Partnership program. In-kind support was also received from the U of A and Alberta Agriculture, Forestry and Rural Economic Development.

Bev Betkowski is a communications associate for the University of Alberta.