Alberta’s canola crush plants may be running at a record-high pace this year — but that only really benefits farmers who are close to those facilities, says a farmer northeast of Edmonton.

“We’ve got it in the bins, but we’ve got no place to haul it,” said Doug Scott, whose closest crush plant is in Lloydminster. “We have limited places to take any kinds of damaged canola. There are better prices offered close to the crushers but we’re not (close), so hauling for us is really out of the question.

Read Also

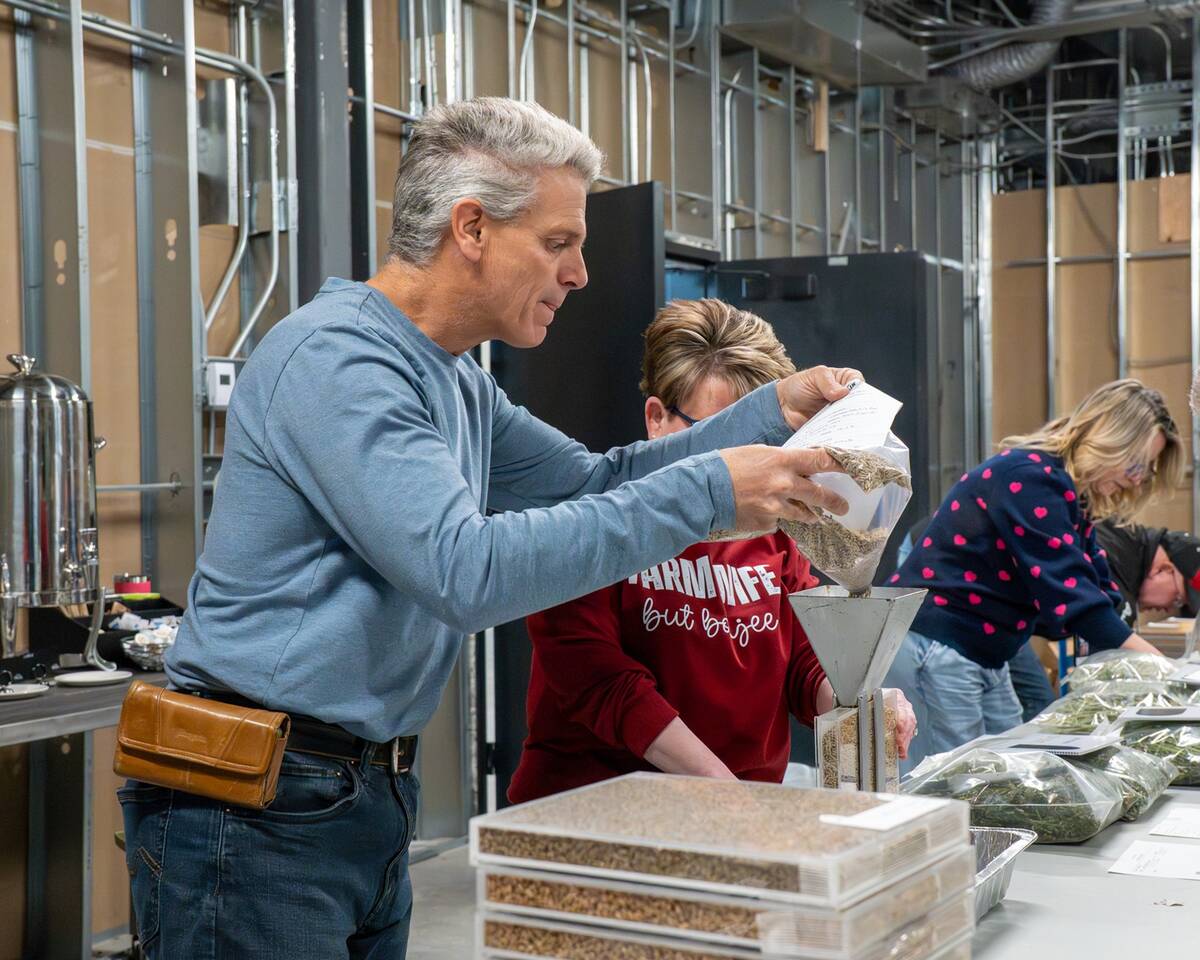

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“By the time we get the discounts, there isn’t a lot left.”

- Read more: Canola ripples felt widely through the Alberta and Canadian economies

- Read more: Handy calculators for canola seeding

Scott is one of thousands of Alberta farmers who were left with damaged canola following a wet harvest. And while that canola sits in his bins, degrading even further, Scott continues to shop it around to find the best possible price.

“You just have to take whatever they’re willing to offer you,” said Scott, who estimates roughly five per cent of his crop was damaged this year.

“They try to tell you that there’s no value in it, even though it crushes just fine. They know they have us.”

After harvest, Scott marketed his damaged canola through a local terminal, where “discounts varied widely.” For canola that was six per cent damaged — “still 94 per cent good” — Scott got about $9.60 a bushel, while canola that was 11 per cent damaged fetched about $7 a bushel. But one load was 22 per cent damaged, and he only saw around $3.80 a bushel for that.

“There is no consistency in pricing, and there are no options,” he said. “If you had a very modest 40-bushel-per-acre yield (on your damaged crops) and canola is now trading for around $11 a bushel, that’s a lot of money if it’s discounted $5 a bushel.”

Getting the best price

But that’s not really very different from any other year, said Neil Townsend, senior market analyst with FarmLink Marketing Solutions.

“There’s always going to be a lot of variable prices for canola or for any other crop in Western Canada,” said Townsend. “There’s local supply and demand. There’s regional supply and demand. There’s national supply and demand. There’s international supply and demand. All of those have an impact on figuring out what the price is.”

Generally speaking, farmers who are closer to crush plants are seeing higher prices than those who aren’t, he said, but even so, “prices have been pretty good this year.”

“There’s been strong demand both offshore and for domestic crush, but the nature of canola is that sometimes one area needs it a little more than another area, so that alters the price,” he said.

“In an area where there’s not as many crush plants and where the main outlet is gathering canola for export, there’s not as much demand. There’s never going to be equality across all regions.”

But with crush plants running, on average, at around 90 per cent capacity so far this year, there will still be a market for poorer quality.

“The damaged canola is a little bit of an X factor,” said Townsend. “If it’s still able to be crushed and the oil content is relatively good, there’s going to be a market for it this year.

“If we can crush it, we can sell it.”

That’s why it’s so important to get “good and representative samples taken by a third party,” added FarmLink’s Jonathon Driedger.

“Buyers will want their own samples, but if there is an independent sample as well, then there’s a neutral frame of reference to work from,” said Driedger.

Producers should also know each buyer’s discount schedule for any grading factors, as “it may not be the same everywhere.” Crushers discount differently from exporters, and the end-use markets may also impact discounts.

“The combination of an accurate and representative sample and knowing what each buyer is willing to pay for that specific quality profile allows farmers to shop around for the right home for their specific grain, and also avoids surprises,” said Driedger.

“It’s a lot of leg work in a year like this — but it’s critical when trying to get the best price.”

Beyond that, it’s a matter of timing, said Townsend, who encourages producers to “consider the bigger market.”

“If I think the reason prices are going up in other areas is because of a general narrowing of supply and demand, my strategy is not to sell right away — I’ll just wait until the demand is willing to pay more for canola in further-afield places,” said Townsend.

“My own sense is that’s what’s happening in Canada right now. We’re basically exhausting all of the nearby supply, and now we need to start getting canola from other areas.

“So when you see higher prices that aren’t just one-offs — more of a broad-based rally — you may want to be a little more patient in your area for the higher prices.”

But for farmers like Scott who have at-risk grain sitting in their bins, waiting for prices to rise might not be an option.

“Canola is very volatile,” he noted. “It doesn’t take very much for it to heat, and canola won’t stay in a grain bin at 14 per cent moisture for very long.

“That’s why farmers like to move their canola really quickly. It’s not a commodity you want to keep in the bin for 12 months because you might just open the door and find a whole bunch of white ash.”