Acidic soil can plague crop producers with nutrient deficiencies and poor root growth, leading to reduced yields.

Soil acidity below a pH of 5.5 will reduce yield for common crops on the Prairies. Yield loss can be significant in soils below pH 5.0. Lime can be expensive, but may pencil out as the most important fertilizer treatment for soils with strong acidity.

Taylor Wallace has acidic soils – including one field with pH below 5.0. That has to affect yield, he thought. So in the spring of 2023, the farmer from Unity, Sask. gave that field 500 pounds per acre of lime.

Read Also

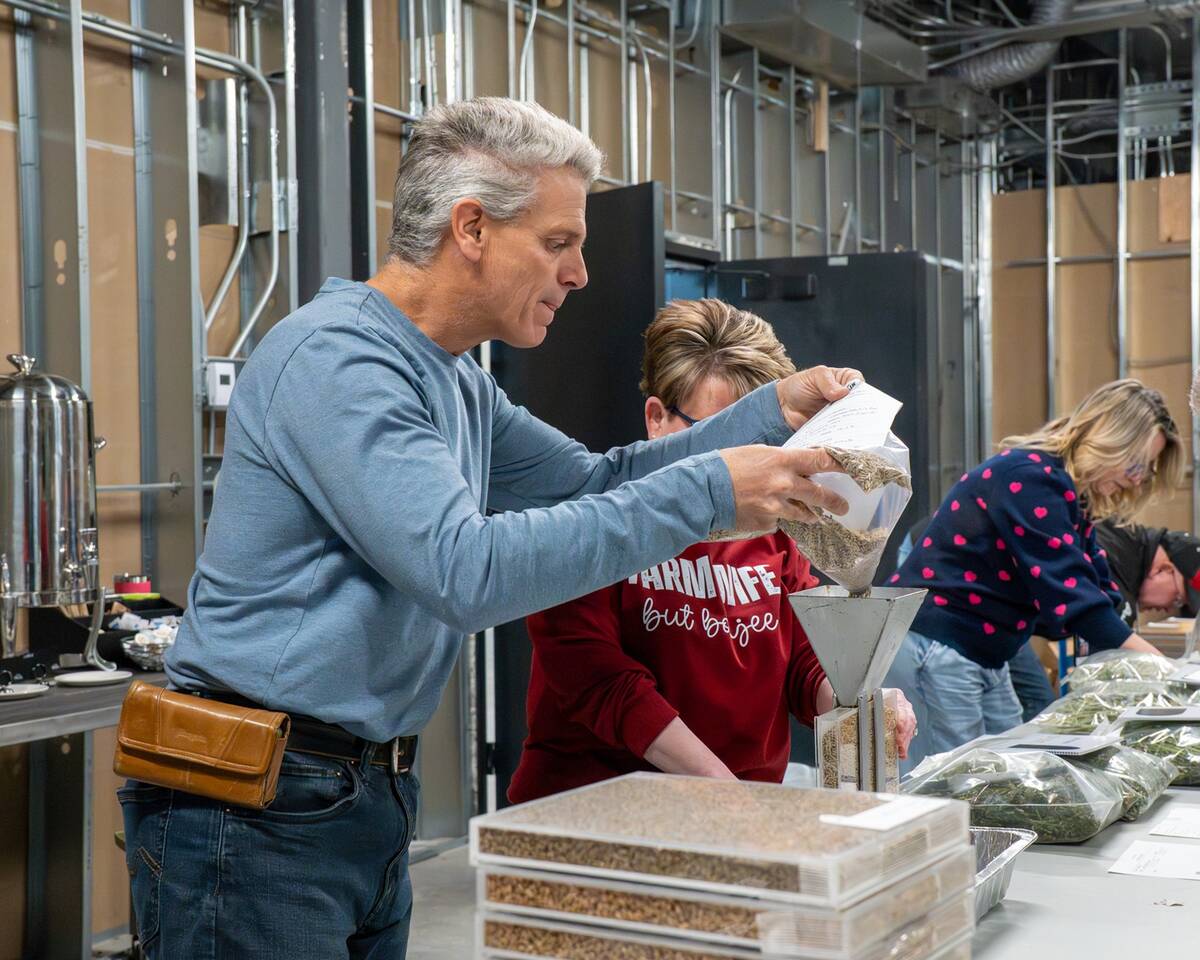

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

A shot of lime reduces acidity. Soil pH below 6.0 to 6.5 starts to hamper phosphorus availability, and this problem gets steadily worse as pH drops. By around pH 5.0, acidity has also released enough aluminum and manganese ions to poison root growth and function.

Wallace paid $530 per tonne for pelletized lime. His 500-pound (227 kg) rate cost him around $120/acre. He based the rate on the experience of a neighbouring farmer, who ran a trial comparing 300, 400 and 500 lbs./ac. The higher rate provided the best results.

“I haven’t seen any results yet,” Wallace says. “Although we did have two fairly dry years in 2023 and 2024.”

Products to increase soil pH include calcitic lime, which is calcium carbonate, dolomitic lime, which also has magnesium, spent lime from water treatment plants and sugar beet processors, and wood ash.

Lime needs moisture to become active, and uniform distribution is key. Lime also requires high rates. One tonne per acre would be considered a low rate to treat soil with pH below 5.0. Wallace applied one quarter of that rate.

Norm Dueck is a consultant for A&L Labs in the Peace River region of Alberta – a region with millions of acres of strong acid soils. He has a lot of conversations about lime. Liming is common practice in acidic soils around the world, and the research is sound, he says. “We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. We know lime will do what it is scientifically proven to do.”

An early 1990s study at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Beaverlodge research centre in northern Alberta looked at lime effects on canola yield and brown girdling root rot. The study site had a soil pH of 5.13 in the top four inches. Researchers applied 7.5 tonnes per hectare (three tonnes per acre) of agricultural grade calcitic lime – primarily calcium carbonate – in May 1991, and tilled it in to a depth of four inches. This increased pH to 6.6 in year one. Canola grain yield increased 37 per cent in tilled soil and 17 per cent in no-till soil. Brown girdling root rot severity went down.

A 1970s Peace Region study, led by Alberta researcher Doug Penney, compared lime benefits for canola, barley, alfalfa and red clover. Researchers limed to a target pH of 6.7. The study concluded that at pH below 5.0, all crops will likely have severe yield loss without liming. For soils with an original pH of 5.0 to 5.5, the lime application increased alfalfa yield 80 to 100 per cent, barley 10 to 15 per cent, and canola and red clover five to 10 per cent.

Despite these results, liming has not taken off in the region. “Sometimes I feel like I’m banging my head against the wall,” Dueck says.

Cost is a big hurdle. Lime cost can vary widely depending on product, location and rate. Transportation is a big component. Soil with pH below 5.0 will need a minimum of two to four tonnes per acre. On top of that, the benefit has a limited lifespan. Lime can be over $100/acre per year, when averaged over time.

However, if acidity affects yield, lime can be the field’s most essential fertilizer.

“In the end, there are no shortcuts or substitutes for raising soil pH,” says John Breker, soil scientist with Agvise Laboratories in North Dakota. “Elsewhere in the world, people have battled soil acidification for centuries, and the answer always comes back to liming.”

Breker has Idaho research showing how quickly yields fall once pH hits a certain threshold. In that study, wheat and barley yields in soil with pH 5.0 were only 60 to 80 per cent of yields in soils with pH of 5.3. The effect started sooner and cut deeper for pea and lentil – yield drop started at pH 5.8 and was down to 50 per cent at pH 5.0.

Where to start?

“The most overlooked factor is the variability of pH within fields,” Dueck says. He has seen many fields that range from below pH 5.0 to 6.5. “You might need two tonnes per acre, or more, on the low pH areas and nothing on the 6.5.”

For a test, farms could start with the most acidic part of their most acidic field. That is what Wallace did. Soil pH probes can quickly identify areas with the lowest pH. With the target area identified, send one composite soil sample to a lab to set the rate.

Lime rate depends on soil buffer pH, a factor of the soil’s cation exchange capacity. Soils with low pH and low buffer pH require a lot more lime. Labs will test soil for pH and buffer pH, and also test lime sources for “calcium carbonate equivalent”. With these tests, labs can provide lime rate guidelines based on lime quality and the farm’s target pH.

Penney, who conducted the lime study in the Peace Region in 1970, is a lime expert. He says lime has “no mobility” in the soil, so it needs uniform distribution. Best results come from powder form applied generally throughout the soil. Penney recommends surface application over dry soil, then heavy harrow to mix dry soil with dry lime, then cultivation to mix it into the top three or four inches.

PHOTO: WARREN WARD

Alternative treatments

Lime is the only real way to increase soil pH. One alternative is to simply live with lower productivity on strong acid soils.

Another alternative is higher rates of phosphorus. This will overcome some of the phosphorus no longer plant-available because of bonds with aluminum and iron.

Some wheat cultivars are more tolerant to low pH. Farmers could ask seed companies if they have data for Canada. Farmers could also look at entirely new crops. Blueberries tolerate strong acid soils. Nova Scotia has strong acidic soils and wild blueberry is the number one export crop in the province. Potatoes, wild rice and commercial grass sod also tolerate acid soils.

Wallace says crop and cultivar decisions may improve results in low-pH soil, and adjusted phosphorus rates may help. But he still sees the need for lime.

“As land becomes more expensive, it becomes more important to get the most out of the land you have,” Wallace says. “Proper soil testing and a variable rate application probably provide the best path to value from lime.”