Being a pioneer isn’t easy, but sometimes it can pay off. Or at least that’s what John Kolk hopes.

Over the past few years the southern Alberta farmer has been using strip tillage on row crops such as dry beans, corn and soybeans. Although the system hasn’t been a big earner in terms of dollars and cents, Kolk is sticking with it for the long-term health of his soil.

“The less disturbance, the less loss of soil biodiversity under the ground,” said the Enchant-area producer.

Read Also

Canada’s $5B forage crop needs a closer look

Forage production is a valuable contributor to the ag economy, ranking as Canada’s third most important crop behind wheat and canola.

“(Strip-till) allows you to leave green roots until your new seedlings are started on at least 60 per cent of your land. You’re giving space for the underground moving creatures like soil mites to have an area that’s not disturbed. I think it’ll help soil health over time because tillage is pretty harsh on soil health.”

A downside is that the practice, though becoming more popular in regions of the U.S., is practically unheard of in Alberta. That means little equipment support, and a lot of trial and error.

“You don’t have the service people so it’s a little bit of a stretch to try it here,” said Kolk. “We checked around and there were only two people we found in southern Alberta that were doing any strip tillage or some iteration of it.

“As in most changes in management, it takes a while to make it work. You’ve got to grit your teeth and work your way through it.”

Strip-till could be considered the middle ground between the soil-warming and drying effects of conventional tillage and the soil-protecting advantages of zero-till. Using special equipment, it disturbs only the portion of the soil that contains the seed row.

Kolk was looking for something that could help protect his crops from wind erosion while disturbing his soil as little as possible. He wondered if strip tillage might help prepare the soil for seed canola as well as row crops such as dry beans and corn.

“We’re in the Palliser Triangle so we tend to have fairly dry soil and high winds,” he said.

“We’re on white soil, which is kind of a sandy loam. With small-seeded crops like canola or dry beans, if you get a bad wind and the plant’s just out of the ground, the soil starts moving and cuts the little plants off. I was looking for a solution that would reduce the wind right at the surface.

“With wheat and barley, you can leave stubble because you can seed direct, but with the row crops we don’t have that option.”

Kolk uses a special strip-till unit to work only the six inches where the seed goes in.

“It warms it up in the spring and then you leave 14 inches in between the rows that hasn’t been disturbed. That way you either keep something growing there or keep stubble there through most of the growing season.”

One of the biggest challenges is weed control.

“The one thing about tillage is there are no weeds that are resistant to tillage,” said Kolk. “So if you’re not tilling, of course you have to figure out what kind of chemistry to use and that’s not always easy with multiple crops.”

The equipment can also present a challenge, he said.

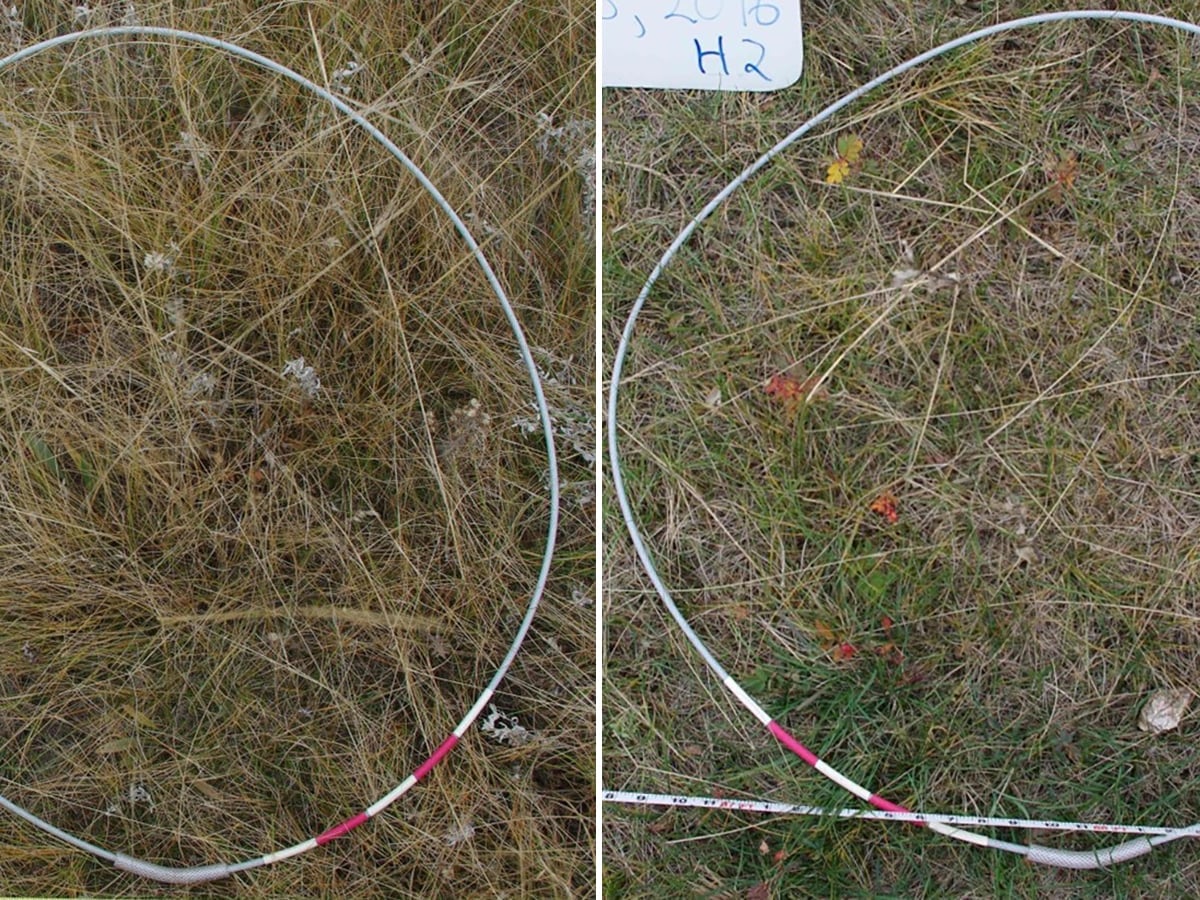

“We have a tillage bar that we put the strip-till units on. Strip-till units tend to look a little bit complicated; they basically have a front cutter wheel to cut the trash and then — in our case — we have a shank that goes down about six inches behind that and it’s got two protecting disks to keep the dirt from flying out too far on both sides of it.”

The practice got off to a bit of a rough start.

“In the first year we tried it on our corn. We started a bit late so we had to seed the corn quite quickly after it. The soil was too fluffy underneath so we lost some germination because of poor seed-to-soil contact.”

A few years of trial and error have increased his confidence, however.

“I thought we had it down last year and then we had a year where some of the chemistries weren’t controlling the weeds,” said Kolk. “So we’re going to make a few changes on that. Depending on the year, we might try a spring cover crop on some of the later-seeded beans and see if that works.

“I would say we’re 80 per cent there, but to make it really work well and with confidence, I think we need to learn a few more things and make a few more changes.”

Kolk is playing the long game when it comes to strip-till. Although he’s seen some efficiencies in diesel use, it hasn’t been a “big win” in terms of yield advantage.

“Two years ago we had a few crops that were probably ahead of the game. Last year we were probably a little behind or average,” he said.

“I can’t call it an absolute win yet. Right now it’s additional costs without necessarily any financial benefit. I’m hoping that a little bit of soil health benefit will certainly reduce wind erosion in a major way.”

Still, Kolk figures it’s only a matter of time — and effort — before strip-till becomes more common.

“I think over time if we can cure some of the issues around weed control and get some people who know how to service these units and set them and whatnot, I think you’ll see more of it in the special crops area.”