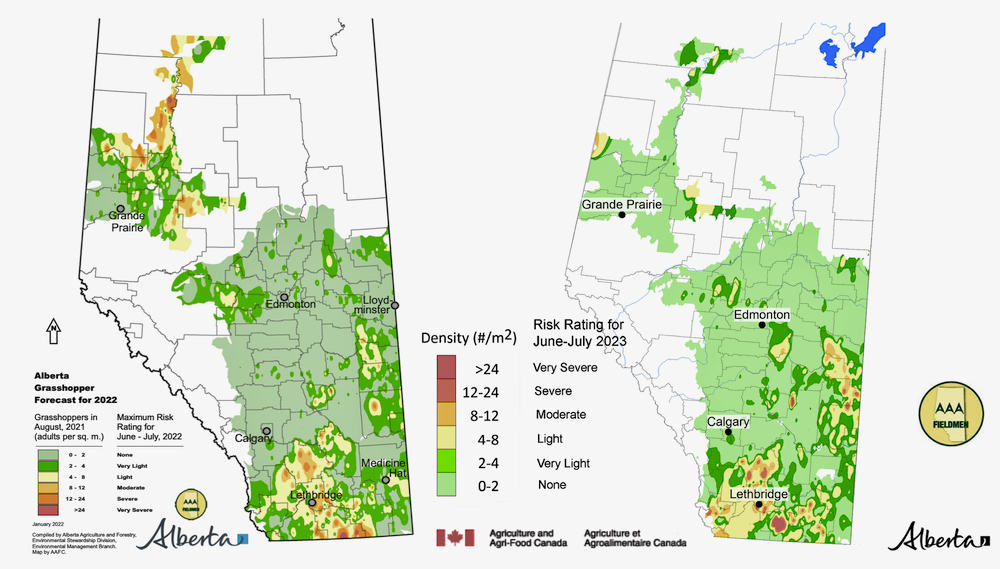

Compare Alberta grasshopper survey maps from the past two years and one thing becomes clear: If you had grasshoppers last year, there’s a good chance you will this year, too — and likely in higher numbers.

“When you look at the map from 2021 and compare it to the survey that was done last year, you’ll see there’s more orange and yellow,” said Shelley Barkley, insect survey technologist with Alberta Agriculture and Irrigation.

That means larger chunks of the province fall into the middle zones of the risk rating maps. (See further down: Yellow means four to eight hoppers per square metre were found during surveys last year while orange is for densities of eight to 12 per square metre.)

Read Also

‘Millions will die’: Foodgrains Bank faces $2.7B federal funding threat

Foodgrains Bank warns $2.7B aid cut triggers a humanitarian crisis, risking global hunger relief and 40 per cent of its funding.

“The population has just grown and spread out,” said Barkley.

Southeast of Lethbridge is a particular hotspot, now rated as very severe (24 or more adult grasshoppers per square metre) — a problem you can blame on the lovely autumn weather.

“We had a great fall in 2021 so there was a lot of capability in the ground,” she said. “We just keep compounding it every year that we have nice long falls — they’re able to lay just about every single egg in their bodies. And they can lay a lot of eggs.”

In southern Alberta, two-stripe, Packards and a variety of migratory species make up the majority of pest grasshoppers. The Peace country has a unique situation with Bruner’s spur-throated grasshoppers mysteriously appearing every odd-numbered year.

“It seems like it takes two years to complete its life cycle,” said Barkley. “So the survey doesn’t really forecast that for the Peace but anyone there knows that in even years you’re not going to have trouble but in odd years there’s a good chance you will.”

Managing outbreaks

So what are your options if you encounter a grasshopper outbreak? First, take a step back before applying insecticide, said John Gavloski, an entomologist with Manitoba Agriculture. Because of the multitude of beneficial insects, he recommends spraying only when the risk reaches the economic threshold.

“If you’re using a broad-spectrum insecticide, you’re taking out the good with the bad,” he said.

(Economic threshold information for Alberta can be found at alberta.ca — search for ‘crop insect resources’ and follow the links to get info on the grasshopper that’s giving you problems.)

There are also options that selectively kill grasshoppers and don’t affect beneficials, added Gavloski.

“We encourage growers to consider those if it’s practical and affordable, because that will help preserve that natural bio-control.”

The organic farming sector also has some insights for grasshopper control.

One is that more complex farm ecosystems — such as intercropping and cover cropping — can reduce insect problems, University of Manitoba plant science professor Martin Entz said in a recent presentation.

In one research project, Entz used pitfall traps to capture carabid beetles (who dine on grasshopper eggs), which were sorted and identified.

“We had three organic systems: A grain-only organic system, one that had green manures in the rotation, and one that had alfalfa mixed with grain crops,” he said.

“What was interesting is that the greatest diversity of plant populations resulted in the most diverse and the greatest number of beetles. So a diversity of plants means the diversity of these beneficial insects.”

More plant diversity also seemed to boost natural resistance.

“Plants actually talk to each other with their volatiles,” said Entz. “They release chemicals, and those chemicals float in the air, and other plants will respond to them.

“A neighbouring plant is going to sense those and turn on some of its self-defence mechanisms. It doesn’t absolutely make the plant immune to that insect, but it certainly increases its resistance.”

Studies have also found that lower densities of plant-eating insects in polyculture fields (like intercropping) is lower than in monoculture fields and there are more natural enemies, especially parasitoids.

“So the pest itself is higher in monoculture, while its enemies are lower.”

Other methods

A push-pull system pushes away pests and pulls them to another place.Grasshoppers, for instance, do not like certain pea varieties, so peas can be planted as guard strips around crops such as flax, which are more susceptible to grasshoppers.

That’s the push part of the equation while perennial strips illustrate the pull part.

“We put a perennial strip around the field because we know the grasshoppers like to lay their eggs in those perennial planting strips, and then we can till them to kill the eggs or kill the nymphs,” said Entz.

Twice-over grazing systems also result in fewer grasshopper outbreaks than season-long grazing. “The reason for that is that it reduced the quality of the habitat for the grasshopper,” he said. “Grasshoppers need to have their temperature regulated, and if you have areas in the field where you’ve got inconsistent temperature regulation, you can make the grasshopper less happy.”

They prefer undisturbed areas to lay their eggs, which is why they often lay them in ditches. As a result, tilling the soil in the fall to make it less desirable for egg laying is an age-old method of discouraging grasshoppers but “there is a trade-off there between soil health.”

“In the Conservation Reserve Program in Texas, they talked about shredding the perennials so you’re not having to till them,” said Entz, who suggests mowing ditches could achieve results. “The dead plant material is less attractive to grasshoppers, so anything that increases the disturbance of the soil will reduce the grasshopper.”

And while there are a huge number of grasshopper species that live on the Prairies, only a handful are harmful to crops.

“There are about 12 grasshopper species of economic pest importance at some times, and of these, only five are considered pest species,” Alberta Agriculture’s website states.

“Landscape diversity is very important,” said Entz. “Things like wetlands allow the other 180 species of grasshoppers to thrive, and when you have greater diversity, you’re going to have fewer of the pests.”

However, Entz admits that the effectiveness of some of these grasshopper control techniques is limited if an outbreak gets out of hand.

“The challenge with grasshoppers is that when they get into really high numbers, they move so quickly that some of these strategies may not make that much of a difference.”