Cow whisperer’ Bud Williams used to have a saying when he was working cattle: “Slow is fast and less is more.”

Now, four years after his death, Bud’s daughter and son-in-law are carrying on that tradition by teaching proper stockmanship — the Bud Williams’ way.

“Cattlemen have been led to believe that the only way to work stock is with force and fear,” said Richard McConnell, co-owner of Hand ’n Hand Livestock Solutions in Missouri.

“And I think that gives you a negative outcome for both the handlers and the stock you handle using those types of techniques.

“There’s an easy way to work stock if you make them work for you.”

Twenty years ago, McConnell never thought he could handle cattle the way he does now, sorting stock in the field without any panels.

“I would have said, ‘You can’t do that.’ But I know now that you can do that because we do it all the time,” said McConnell, who is married to Williams’ daughter Tina — an experienced stockperson in her own right.

“It’s something that comes with practice, patience, and experience — nothing else.”

Proper stockmanship is livestock centred, behaviourally correct, psychologically oriented, ethical, and humane, said McConnell, who spoke at a stockmanship clinic near Red Deer in mid-June. But that doesn’t mean you have to lose money on it.

“My No. 1 priority as a producer is to make a profit. If you’re gaining more weight — a quarter- to a half-pound of gain a day — on these calves that are handled better, that’s going to be profitable,” he said. “Happy animals produce better and if we want a good result, then one of our main objectives should be to keep the animals happy.”

In most cases, that starts with communication, said McConnell. And if you don’t think your cows can talk to you, you’re not listening hard enough.

Read Also

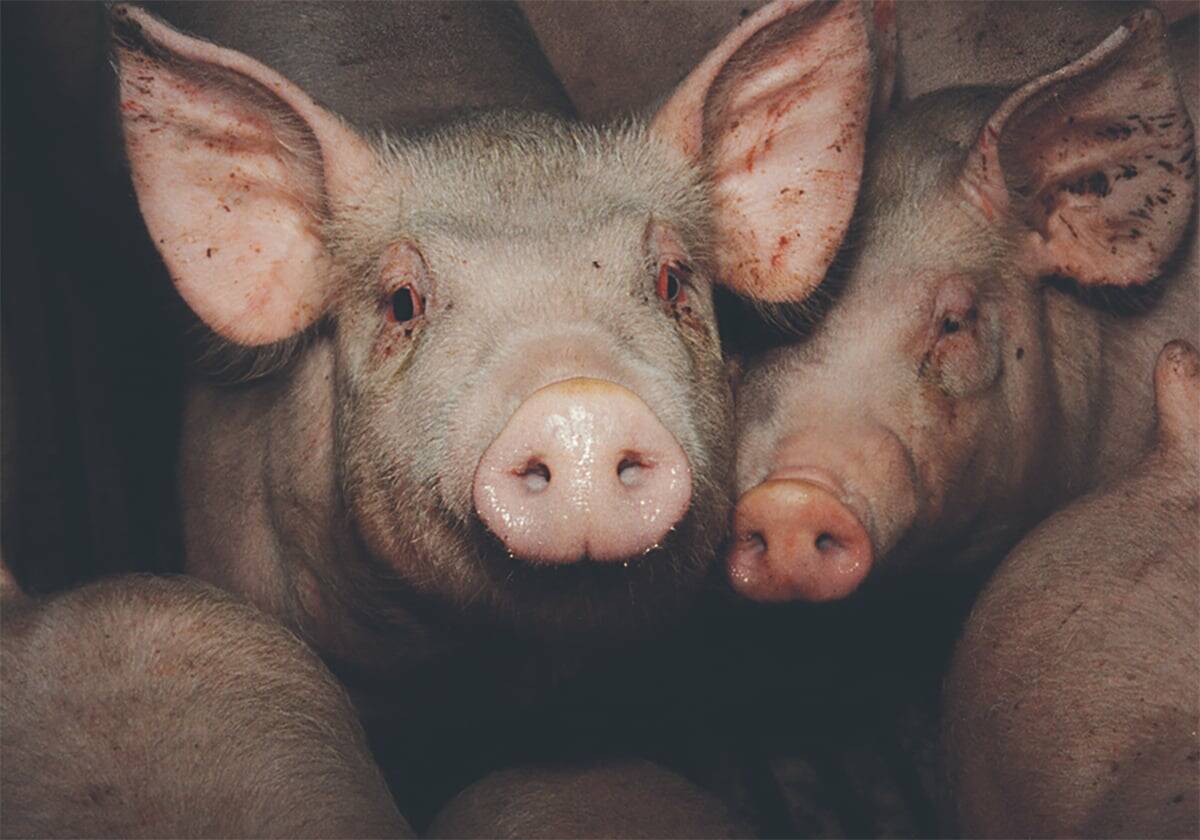

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

“The stock are trying to tell you that they either like what you’re doing or they don’t like what you’re doing,” he said. “It becomes a communication and an understanding between you and the stock.”

Cattle “immediately begin trying to communicate” once you step into the pen with them.

“Animals have a twitch of the ear or a twitch of the tail, and they’re telling you something with that. If you’re not looking for these things, I guarantee you won’t see them. And if you can’t see it, you’re not going to change.”

Pressure and release

The first step is learning how to apply proper pressure to the cattle — and when to release them from it, said McConnell.

“I try to set it up so that it’s the animal’s idea to do what I want them to do,” he said.

“I ask them to do something, and when they do it, I reward them with the release. The animals must learn to trust us. If they know what we’re asking and they do it, we reward them by releasing that pressure.

“You have no idea how quickly this trains cattle and how quickly they pick it up.”

Sometimes, though, that means you have to “swallow your pride” and learn to take two steps back.

“Backing up is so easy to do, but your body doesn’t want to do it,” said McConnell. “Our body is trained to keep pressuring and then pressure some more if they don’t go. But we’ve all seen the result of that.”

Backing up accomplishes three things — it draws the animals toward the handler; it slows the animals down; and it relieves the pressure, allowing time for the handler to make adjustments.

“It’s a wonderful tool to learn to take two steps back,” he said. “It’s the building blocks for how we’re going to approach animals to get a positive response from them.”

Cattle have several instincts that producers can learn to use to their benefit.

“If we apply those at the right time and the right place, in the right order, we get a good result,” said McConnell.

“I want it to be easy. The less I have to do, the better I feel about it.”

And in most cases, he added, that means abandoning the ‘cowboy way’ of using ‘force and fear’ in favour of a less-is-more approach.

“I know the cowboy way. We’ve all got hats and buckles and a Ford pickup. All those things are great. But if there’s an easier, better way to get the job done than doing it the cowboy way, I’m all for it.”