A horse’s behaviour when being mounted is rich with information regarding how it physically, mentally and emotionally feels about the experience.

How is the horse coping, adapting to and/or counterbalancing the activity of the mounter? If it braces itself, hollows its neck or back, raises its head, pulls its ears back, swishes its tail or moves about and does not settle to be mounted (and even walks off), then something is amiss.

Although unsettled behaviour is often treated as a ‘training issue,’ the horse may simply be looking to alleviate discomfort. Mental anxiety is more common than simply being poorly mannered. Making the horse stand still and tolerate the discomfort does not address the root cause of the behaviour.

Read Also

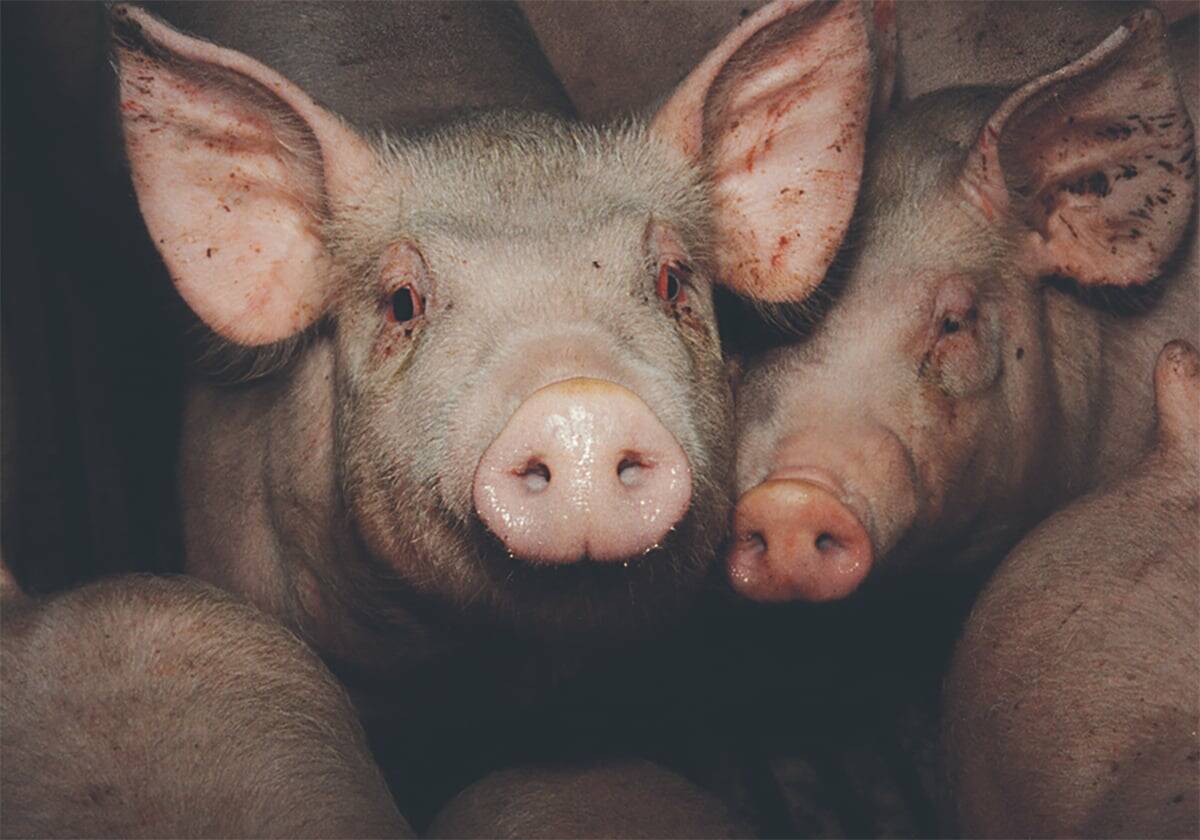

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

Mounting prowess requires a level of fitness by the rider. Think of the ability to do squats, many squats. Ideally the rider mounts gracefully and the horse calmly accepts the rider and shows no negative expressions. However, what more commonly happens is an awkward, less graceful mount whereby the mounter weights their foot fully in the left stirrup and this movement pulls the saddle off centre, twisting the horse’s spine with it. Both the horse’s withers and the saddle are torqued at varying degrees to the left.

Anatomically the horse’s wither is comprised of approximately eight vertebrae, each with a long projection of bone like to a sail coming out of the vertebrae. Some of these vertebral processes or ‘sails’ can be as long as eight inches and can act like a long lever arm, amplifying any leverage placed on the spine and impacting tissues both near and far.

Repeated torquing of the withers can cause damage to the horse’s spine including thoracic subluxations, scapular asymmetry, thoracic paraspinal pain, fascial tie down and formation of scar tissue over the withers. Some horses may even develop a telltale patch of white hairs on one side of the withers indicating the distress.

Over time a common sequel to the disordered withers is a sore back and a variety of compensation patterns in other regions.

The horse has a long and graceful spine that can carry up to 20 per cent of its weight but is unable to withstand the pull of a rider’s weight from the side without harm during an awkward mount. Many awkward mounts begin from the ground. A mount with a good, strong bounce from the ground and a healthy grip on the horse’s withers and saddle have a place and time. Unless the mount is well executed, the habit is not harmless and it may be beneficial to use a mounting block, even if only occasionally.

New research has given us insight into the value of a mounting block. Computer systems that measure pressure distribution under a saddle and across the horse’s spine while being mounted have shown that mounting from the ground caused the most pressure on the withers.

Comparatively, the use of a high mounting block (three steps) with no pressure on the stirrups produced the least amount of pressure. The saddle movement itself across the spine was also considerably reduced with the use of a mounting block.

Although there’s less scientific information regarding the dismount, the same principles apply. Drop both stirrups and hop off where possible, as opposed to a long-drawn-out cling and slide off the saddle.

A mounting block can also be better for a rider’s own back and extend the life of the saddle. Especially for the lesson horse, camp horse or rental trail horse, as well as for the less experienced or less agile equestrian, use of a mounting block brings numerous advantages.

It can be a valuable tool in properly educating and developing the horse to comfortably accept a rider. If it willingly approaches and lines up with the mounting block, and then stands comfortably and awaits mounting, then the horse is likely to be OK with being ridden.

If not, it is the responsibility of the mounter to question the source of the reluctance and address it before it escalates into unwanted behaviours.

As humbling as it may be, a person must accept that the horse may be using this opportunity to communicate a powerful concern.