It could take months for grain movement to fully recover from the catastrophic flooding in B.C. that buried rail lines in mud and debris or washed away the ground under the tracks.

And the unprecedented damage has highlighted the risk that Prairie farmers face in getting their grain to port.

“The rail system there has always been vulnerable,” said Mark Hemmes, president of Quorum Corporation, which monitors the grain transportation system. “Probably some of the toughest railroading in North America is through that throat between Kamloops and Vancouver.

“You’re going through the Fraser Canyon where there’s a big river at the bottom of it and mountains all around it. They’ve always had to contend with slides and washouts.”

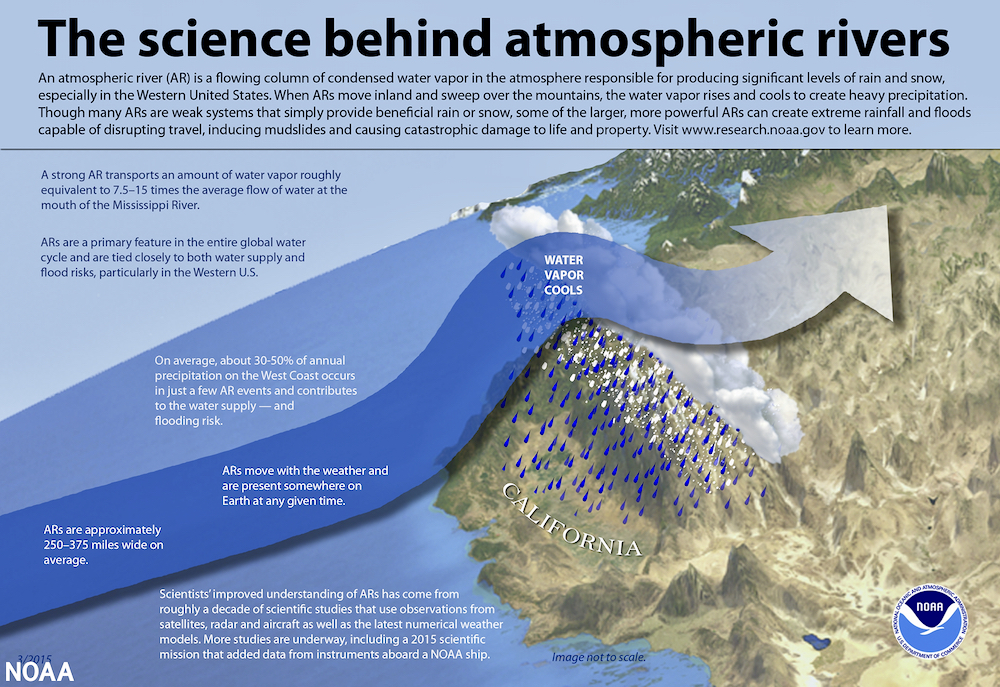

But the devastation caused by what meteorologists call an ‘atmospheric river’ was unlike anything he’s experienced, said Hemmes.

- Read more: The threat from ‘rivers in the sky’

“We see it every year — we just never see it at this level of magnitude. In my 40-some-odd years (working in the rail transport sector), I’ve never seen so many washouts and so many slides occur at one time.”

As the Nov. 29 issue of the Alberta Farmer was going to press on Nov. 23, CP Rail was reopening its line from Kamloops to Vancouver after a marathon repair effort. It said crews had used 150,000 cubic yards (30,000 one-ton dump truckloads) of earth and riprap to shore up or rebuild 30 damaged sections. And it warned “there remains a difficult road ahead.”

CN Rail said it was planning a limited reopening on Nov. 24 “barring any unforeseen issues.”

Read Also

Aster leafhoppers: An unwanted guest migrating from U.S. for canola

Research scientist talks about the prevalence of aster yellows in canola in Alberta, with testing on its pest carriers and conditions in which it affects yields.

But neither had released assessments on the extent of the damage or estimates of when normal traffic running at normal speeds might occur.

The Fraser Canyon was hit particularly hard, with numerous washouts including a rail bridge and train derailment near Boston Bar. CN Rail and CP Rail operate that stretch of tracks as a double track, with trains moving down to Vancouver on one side of the canyon and back up on the other.

Normally when there’s a rail disruption in the mountains, only one of the lines will be impacted, so it’s possible for trains to be rerouted and some traffic to move.

But in this case, both lines were knocked out, and “it’s going to take quite some time for the supply chain to normalize,” CN Rail’s assistant vice-president of grain David Przednowek said on Nov. 19.

“There’s a lot of traffic staged on both sides of the outage beyond the grain that wants to move, and it will take time to work through that accumulation of traffic,” he said, adding the area is still unstable and vulnerable to slides.

“It’s not something where the line opens up and everything is back to the way it was.”

And even when rail service is fully restored, the railways will face a backlog of shipments of all sorts that arrive or leave from Canada’s busiest port.

“The vast majority of Canadian trade on the export side goes through the Port of Vancouver,” said Hemmes. “You can pretty much count on half the grain supply going through the Port of Vancouver, and with that loss, it’s all going to be delayed.”

Downstream effects

It helps that grain volumes are down this year because of drought, he added.

“If you’re a glass-half-full kind of person, you might say it was a good thing that it was a low-production year,” said Hemmes. “It’s not like we’re going to come out of the crop year with a big carry-forward stock. This stuff will move.”

Until the washouts and slides, grain movement had been going “pretty good” since harvest, with between 800,000 and one million tonnes moving every week for the 10 weeks leading up to the rail closures. But that started to slow down even prior to the flooding, and at that point, the slowdown was expected to become “pretty massive” into January and February. Now it could carry on into spring.

“There are going to be issues for the next couple of months,” said Hemmes. “I think we need to get our heads around that.”

As of mid-November, there were roughly 20 vessels off Vancouver waiting to load grain.

“There’s more ships arriving all the time because this is the peak season for transporting grain,” said Barry Prentice, professor of supply chain management at the University of Manitoba. “Nothing is moving off the terminal, and that just adds to the existing congestion.”

The impact is even greater on shipping containers, Hemmes added.

“The biggest way that they get containers off of the dock is by rail, and if they don’t have rail service, pretty soon those docks will be chockablock and they won’t be able to unload vessels,” he said.

“When you start to think about it, the ramifications of this are exponential.”

But again, the lower volumes produced this year shortens the time it will take to catch up.

“When the rail lines open again, the demand for Canadian grain will still be there, and we’ll have the rest of the year to clear off this mess,” said Hemmes. “If this would have happened this time last year, it would have been a huge calamity.”

Grain will also continue to move through the Port of Prince Rupert, and there may be an opportunity to shift some trains north, depending on how long the outage lasts.

“There’s always really heavy emphasis on West Coast shipments given that the Pacific is where most of the demand growth has been over time, but there are a lot of routes the grain can take,” said Przednowek, pointing to supply chains into Eastern Canada and the U.S.

Even so, grain isn’t as interchangeable as it appears given the different markets and quality specifications, so “some commodities can be moved around, while others can’t as readily.”

“The supply chain can’t immediately just shift and do a bunch of volume to Prince Rupert,” said Przednowek.

“That being said, given that grain volumes are significantly down year over year, there is terminal handling capacity to move grain through the Port of Prince Rupert, both for containerized grain movement, as well as bulk.”

Future risks

In the short term, though, getting grain moving to — and through — Vancouver is “top of mind” for the railways.

“All of the stakeholders in the supply chain, including CN, are always focused on ensuring that traffic can move,” said Przednowek. “It’s the movement of the economy.”

Both railways have invested in the ports and the track system through the mountains in recent years to improve the resiliency of the network, he said.

“When events like this occur, it makes people think a lot more about prevention in the future and the ability to recover. This is an exceptional and unprecedented event, but it does demonstrate that resiliency in the supply chain is very important.”

For Hemmes, this year was “almost a perfect storm.”

“We went through the whole summer where everything was heated and dried out, leading to forest fires, so all the vegetation that would have held everything in place was dried up and burnt,” he said.

“And when you put 200 millimetres of water on top of it in one day, this is what’s going to happen. In the short term, there are some pretty big challenges to get ourselves back on our feet.”

But as the effects of climate change become more severe, these types of catastrophic rain events could become more frequent.

“We need to come to grips with that,” said Prentice. “Climate change’s fingerprints are all over this, just like they are with the fires and the drought we saw this summer.

“There’s not a single city in Canada that’s protected against the kinds of storm cells that can emerge. Everything has been built for historic numbers, and those historic numbers are no longer valid.”

But Hemmes said he doesn’t see this as “a calamity that’s going to keep happening over and over.”

“I think we have to put more faith in the people who are managing it,” he said. “If you look at it in a global sense, Canada is just as good as — if not better than — anybody else in the world at moving products, grain in particular. To many, we are the envy.

“We’ve built a pretty strong industry on what we’ve got today. So I think we have to fix what we’ve got and learn our lessons from it.”

On that score, Prentice agrees.

“These things can catch you by surprise the first or second time, and everybody can be given a pass for that, but if it happens a third time, we may have to question things,” he said.

“In some ways, this is a shot across the bow of what climate change could portend. Support for changes to deal with that is within all our interests.”

– With staff files