After a winter of exceptionally low river flows, above-average mountain snowpacks are coming to the rescue of the Bow River and many of southern Alberta’s irrigation districts, says a leading water scientist.

The water supply is now “assured” for the irrigation districts that take water off the Bow and Red Deer rivers, said John Pomeroy, a USask professor and Canada Research Chair in water resources and climate change.

That’s a welcome change given that in November, the Bow’s pre-diversion flows were among the lowest in the river’s recorded history.

Read Also

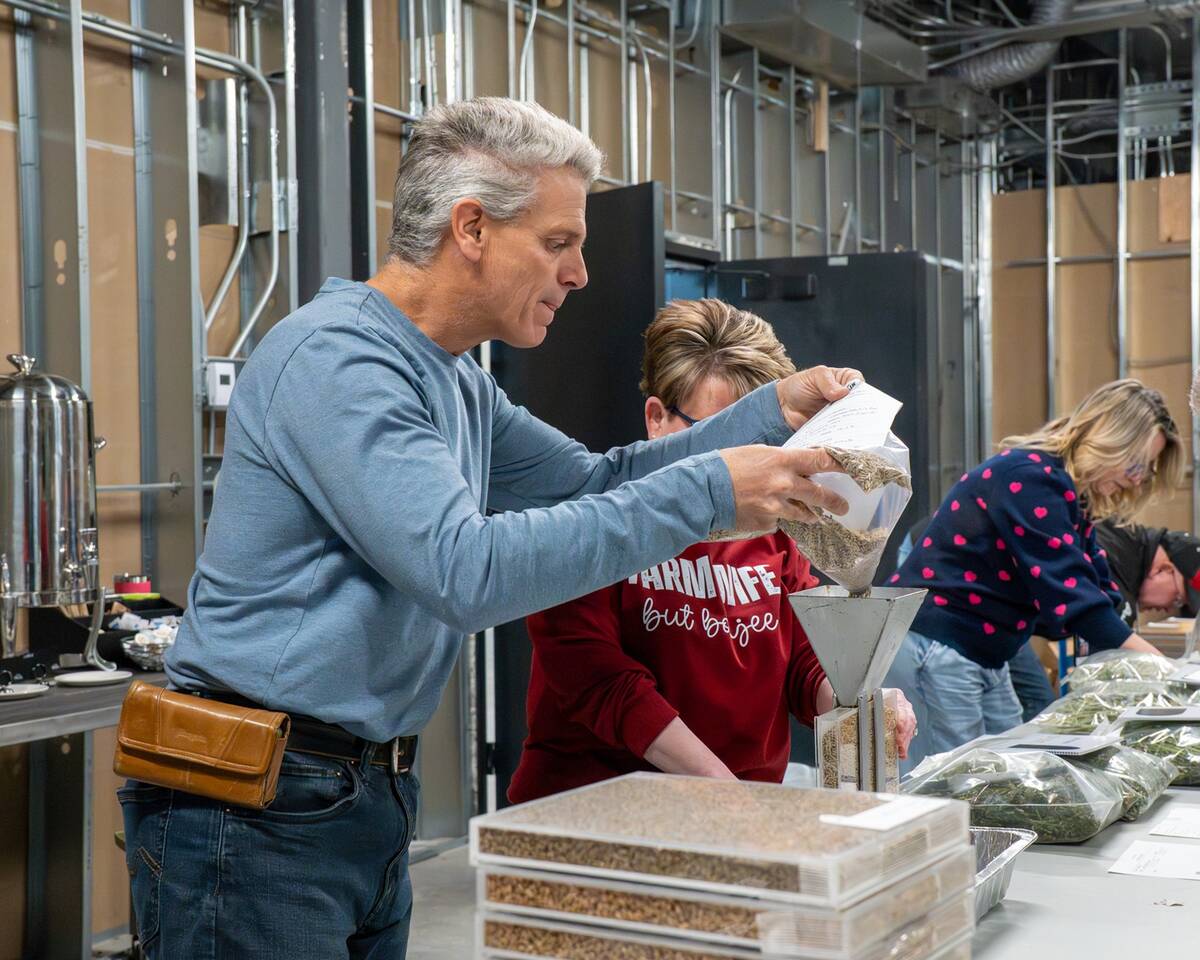

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Most irrigation districts stand to have average water supply coming into spring, although some southwestern regions are still looking questionable, said Pomeroy.

“As you get down towards Waterton and Glacier Park, the snowpack there is normal to a little bit below normal. The very southern irrigation districts are still a little bit shy and could use more snow.”

That doesn’t mean irrigation farmers are completely out of the woods, however.

“They’ll probably be irrigating more than normal to overcome the dry conditions from the fall,” said Pomeroy. “The soil moisture levels for most of south-central and southern Alberta are still about half of where they should be at this time of year. The precipitation since Oct. 1 is only half of what it should be.

“There were people observing dust storms across the Trans-Canada just a few weeks ago back in February.”

On the other hand, some may be facing a spring with too much water as there are “exceptionally high snowpacks” from Edmonton northward.

“They’re very high in the Peace River district,” said Pomeroy. “They can’t completely discount flooding.”

Feeling confident

The three irrigation districts that take water off the Bow — the Eastern, Western and Bow River districts — are all in “great shape” based on reservoir levels alone, said Glenn Logan, a director with the latter.

“The mountain snowpack is above normal but even with a poor snowpack there would be plenty of water available next summer,” said Logan. “We would only be in potential trouble if we started the season with reservoirs well below normal levels and had poor river flow and had low rainfall in the district.”

So what would his irrigation district do if southern Alberta faces another year of drought?

At a certain point the need for rationing would take place, but Logan said a lot would have to happen — or not happen — first.

“If we can maintain our levels going into (next) winter and add to basically full reservoirs, we have nothing to worry about,” he said.

“Where we may run into trouble is if our reservoirs are low in the fall and we don’t get them full before the winter begins, which has never happened before.”

Even then, a normal winter would restore water supplies.

“We get most of our snow in the watershed areas in March and April,” said Logan. “We still have a long ways to go yet.”

In the past, the Bow River Irrigation District has intentionally kept reservoir levels low in order to accommodate infrastructure repairs in the off-season, Logan noted. In every case there was no harm done.

“In each instance, reservoir water levels were able to be replenished before the start of the irrigation season. But I guess when it comes to agriculture, one can never say never.”

Better forecasting needed

Pomeroy is not so confident due to the sheer unpredictability of weather today.

“Things are going on all the time,” he said. “We have to accept more extremes of floods and droughts.”

Last summer’s drought in Alberta was an extension of a “megadrought” that has been going on in the southwest United States at least since weekly drought monitoring began in 2000. (A megadrought is defined as a drought that exceeds 10 years.)

“It’s the worst drought in over 1,000 years in the U.S. southwest,” said Pomeroy.

The megadrought has been known to sneak into Alberta — particularly the southern regions — periodically. Last year, however, it went even further afield.

“We were connected to the megadrought last year as the total drought area stretched south to north from Mexico to Yukon and west to east from B.C. to the Maritimes.”

Canada needs more resources to help farmers take measures to secure their crops against drought, said Pomeroy.

His recommendation is to create an organization similar to the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration, which was created during the Dirty ’30s but was shut down a decade ago.

“It had that presence of agricultural engineers and scientists working with farmers to help them work out new ways to manage water, whether it’s dugouts or trapping snow or improving irrigation efficiency,” he said. “Those are all really useful things.”

A similar initiative is in its formative stages.

“There has been a Canada Water Agency proposed at the federal level that would be a co-operative agency working with provinces and communities to better manage water across the country,” said Pomeroy. “I’ve noticed that soil and water conservation have been listed as some of the things they’re looking at doing and I think that would be a tremendous help.”

Canada also needs better “water forecasting,” he said.

Although weather forecasting has improved dramatically over the past few decades, there needs to be an expanded focus on water beyond river flows.

“The forecasting that’s done by the provinces tends to be for river flow,” he said. “We need longer-term water forecasting which ties into longer-term weather and climate forecasting. The water forecasting itself would be for things like soil moisture, dugout, pond and small stream levels that aren’t currently forecast.

“We are the only G7 country without that kind of a system and I think we desperately need it. It’s putting our producers at a disadvantage to not have that.”