Nearly three years after the province tried, and failed, to open the Eastern Slopes to coal mining, this iconic piece of Alberta is still under threat, say those who live and work there.

“We have to make sure that this land is going to continue for generations,” said Laura Laing, a Nanton-area rancher and part of a grassroots group battling to protect the area. “We can’t continually stack resource development on these sensitive areas, you know? We’re at a maximum right now.”

Laing and husband John Smith have been fighting to ban coal mining in the southern Alberta Eastern Slopes since the provincial government abruptly rescinded a decades-old coal policy in May 2020.

Read Also

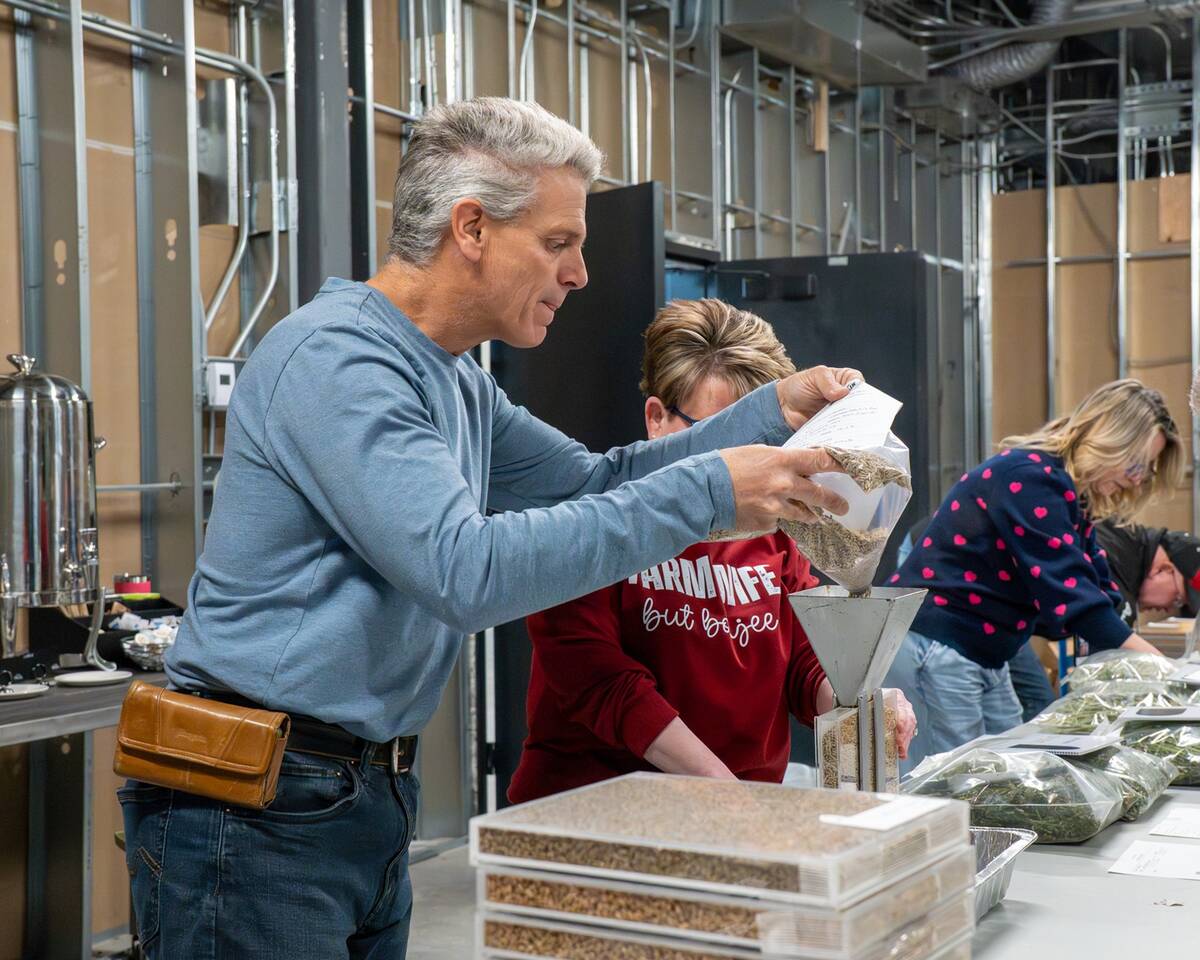

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

The resulting furore, first from local residents and then organizations, celebrities, civic leaders and the general public, eventually forced the government to back down. But while they were fighting, coal companies moved in, applied for leases and did exploratory work on previously protected sites.

[RELATED] It’s a golden child, but rough fescue is disappearing

A trio of Australian companies pursued six mining projects, according to the Livingstone Landowners Group, which is named for the Livingstone-Porcupine region, an area of about 4,500 square kilometres that is part of the Eastern Slopes.

“They brought bulldozers into environmentally sensitive areas and just went at it,” said Norma Dougall, president of the group. “It just shows the sort of wild west of the coal industry. The assumption there is it’s going to be an open pit and it’s going to be gone anyway, so who cares?”

With mining development off the table for now, companies aren’t motivated to remediate that environmental damage, said Dougall.

In the 11-month window before the coal policy was reinstated, the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS) says significant damage was done by mining companies as they explored. The government approved more than 700 drill sites and 250 km of roads in the region.

In addition to economic activities such as tourism and logging, the region provides wildlife habitat and is a critical source of water for cities and towns downstream as well as the irrigation districts of southern Alberta.

“The big issue with the coal fight is that they were proposing putting large-scale industrial developments and open-pit mines in the headwaters of the water system, which would impact everybody downstream whether it’s agricultural users, whether it’s recreational users, whether it’s municipalities. It has a huge risk with it,” said Dougall.

The slopes of the Rocky Mountains are also home to some of the most productive grasslands and oldest ranching communities in the province. Area ranchers were among the first to learn that the policy had been silently lifted.

“As soon as they opened the doors and the welcome mat happened, we were getting contacted by various coal companies,” said Laing, who owns and operates Plateau Cattle Co. near Nanton, with her husband. “I think anybody with a very basic understanding knows that we can’t have coal mines and cattle in the same area.”

Laing said the couple depend on their grazing lease near Cabin Ridge in the Mount Livingstone area. Their cattle gain 10 per cent more weight when grazing there than in the valley. Those grasslands are also more resilient in years when the dugouts down below dry up, she added. (For more on foothills fescue grasslands, see accompanying story.)

“With the increase of extreme weather experiences, like the drought that we’ve been under for four years here in southwestern Alberta, if we didn’t have a resource to go to, we’re losing pastures,” Laing said. “Access to areas like the mountains is so vital to us because of the water and because of the grasslands.”

Even without open-pit coal mines, the region is under considerable stress, say conservationists.

Recreation and industrial activity have damaged the Livingstone-Porcupine region, and the density of roads and trails is four to five times greater than the limit for healthy waterways and habitats, according to CPAWS.

“We can’t continue to do everything everywhere, all the time,” said Katie Morrison, executive director of the society’s southern Alberta division.

“We really do need to look at the value of those places, the ecosystem services they provide, like water, that are irreplaceable.”

As in 2020, the threat could again be unleashed with no public consultation. Premier Danielle Smith has mused about reopening the debate on allowing coal mining in the region and when asked about that in November, her energy minister said that for now, he was keeping the ministerial order that restored protection in the area.

But Peter Guthrie wouldn’t say how long the order will stay in place.

“I don’t have an answer on that,” he said. “But for now, there are no changes planned.”

That nebulous stance has prompted mining opponents including Dougall, Laing and Morrison to continue a push for government to create a new coal policy backed by legislation.

A coalition that includes local ranches, conservation groups, hunters, anglers, businesses and municipalities collaborated to create a policy they want the province to adopt. It calls for no more coal mines, along with rules (backed by bonds and enforced by the Alberta Energy Regulator) that would provide “timely and effective remediation of lands disturbed by coal exploration and mining activities.”

“The Eastern Slopes is important to us as it is and it should be kept as it is, intact, not open to large-scale development that will have decades of contamination and mitigation required just to keep the water safe,” Dougall said.

“Not to mention, what do you do with the rest of the ecosystems there that have been destroyed? You can’t make an open pit mine back into pristine wilderness. You can seal it over with something but you will never make it back to what it was.”

Anything short of legislation isn’t a sufficient safeguard, added Laing.

“We want to see a guarantee of protections so that we don’t have to be the front line fighting to protect these areas, or with a simple government ministerial order have it overturned again. We fear that.”

With no indication that the provincial government will provide enduring protection, the advocates say they are ready to maintain pressure. In 2024, a provincial land-use framework for the South Saskatchewan Region (covering the 84,000 square km in the southernmost part of the province) is up for renewal and advocates want the next edition of the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan to include a ban on coal mining.

It will be another battle in what has already been a long series.

“Traditional ranching is hard enough without having to defend the landscapes for the right to be in the industry,” said Laing.