Shaped by wildfire and grazing herds of bison, the fescue grasslands of Alberta dominated the Northern Great Plains until the soil attracted settlement that pushed out native prairie.

What’s left remains under threat, advocates say, but there are ways to protect it.

“I grew up with a father that was very entwined in the importance of rough fescue,” said Sarah Green. “That grass is really important for our operation.”

Read Also

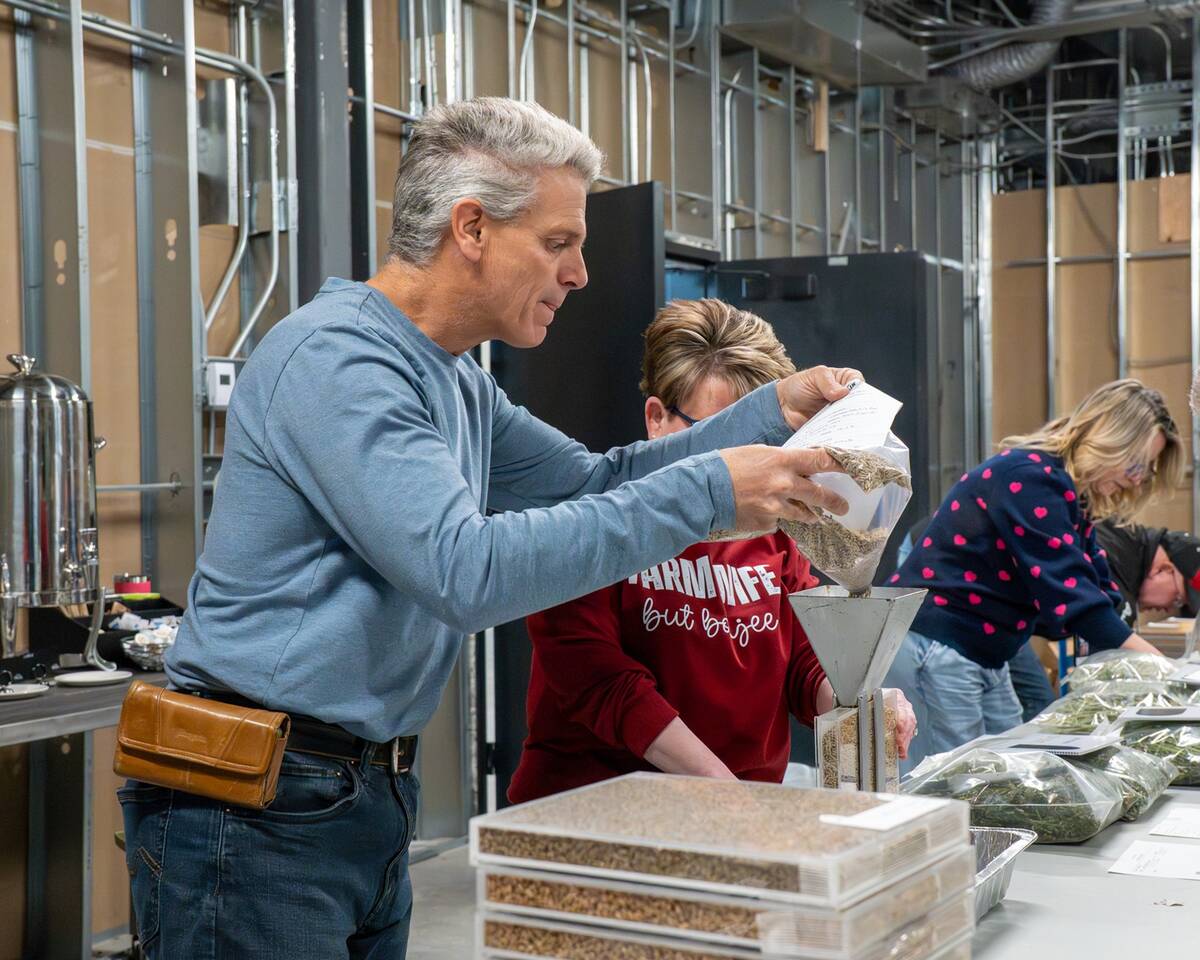

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Green, owner of Mount Sentinel Ranch near Nanton, comes from a long line of ranchers. Her family has grazed cattle on foothills fescue grasslands since 1898.

“It’s kind of our golden child for the ranch,” she said.

[PHOTOS] The rough fescue grasses of Alberta

Rough fescue is a densely tufted bunchgrass. Three varieties grow in Canada: Plains rough fescue, foothills rough fescue and northern rough fescue.

What makes these grasses unique, Green said, is that unlike other grasses, they cure on long stems above ground, keeping palatable high-quality nutrients available even in deep snow.

She has come to count on that.

“It’s by far our best winter feed. It holds protein really well. It allows us to graze cattle through the winter and not have to feed them as much. You’re not having to pour money into hay.”

Green’s relationship with rough fescue is reciprocal. While it’s hardy, it requires care to manage and maintain, and once it’s gone it’s often gone for good.

Human activities and invasive species are the greatest threats to fescue grasslands, and attempts to re-establish rough fescue after land development have been largely unsuccessful.

In the foothills fescue grasslands of southern Alberta, where Green grazes, rough fescue once covered approximately 3.8 million acres. It’s not clear how much is left, but a two-decades-old report by the Alberta government estimated more than 83 per cent had been lost by 2003.

“Once you damage that kind of rough fescue grassland, it is very, very difficult to get it back – if not impossible,” said Stephanie Jaffray, a rangeland agrologist with the Prairie Conservation Forum.

“If you’ve got a stand of it, it’s so important to maintain it and take care of it. It’ll pay off in the end because you don’t really have to think too much about it, except for letting it grow and being able to use it sparingly.”

The plant evolved under winter grazing by bison herds. Even light grazing in spring can damage the grass, so it shouldn’t be grazed until after its flowers disperse in July.

When it is grazed, Jaffray said, she recommends leaving 50 per cent untouched to protect the plant. Uneaten leaves make litter that protects the soil biome and conserves moisture, helping rough fescue resist drought and fire.

“It’s like insurance,” Jaffray said. “If you’ve got a good native grassland, you’re probably going to have some kind of production that’s useful.”

Green has learned to read fescue stands and uses adaptive grazing to manage pastures and keep them productive over winter.

“It’s a very complex system, but it’s an amazing system because it’s adapted so well to be grazed,” said Green. “It’s used to being grazed, as long as it’s done in a sustainable way.”

There are simple ways to protect rough fescue, Jaffray said.

Producers can distribute minerals and move salt to get livestock grazing more of a pasture. Portable electric fences can keep cattle away if moving pastures isn’t an option.

The Prairie Conservation Forum offers free range and wildlife assessments and funding for habitat improvements,

“We don’t want people going out of business trying to manage wildlife and range health,” said Jaffray. “We want people to be able to make a living while protecting ecosystems at the same time. That’s our goal.”

Healthy grasslands offer benefits to wider society. In addition to ameliorating downstream flooding and providing drought resistance, they capture nearly as much carbon as a forest. But they’re disappearing at a rapid rate.

“It’s dwindling every year,” Green said. “It’s becoming a smaller and smaller ecosystem where you see a really good rough fescue stand.”

Populations will never truly recover, she said, but mindful grazing and land management can help protect more of what’s left.

“We’re never gonna go back to a rough fescue stand like we did have 100 years ago. It’s just not plausible,” Green said. “(But) we can still make really healthy soil and still create really healthy grassland.”