[UPDATED: Aug. 24, 2023] Farmers and other rural residents face disadvantages when it comes to emergency services. Distance and logistics are two big factors, but they don’t end there. Just ask Kim Ruether.

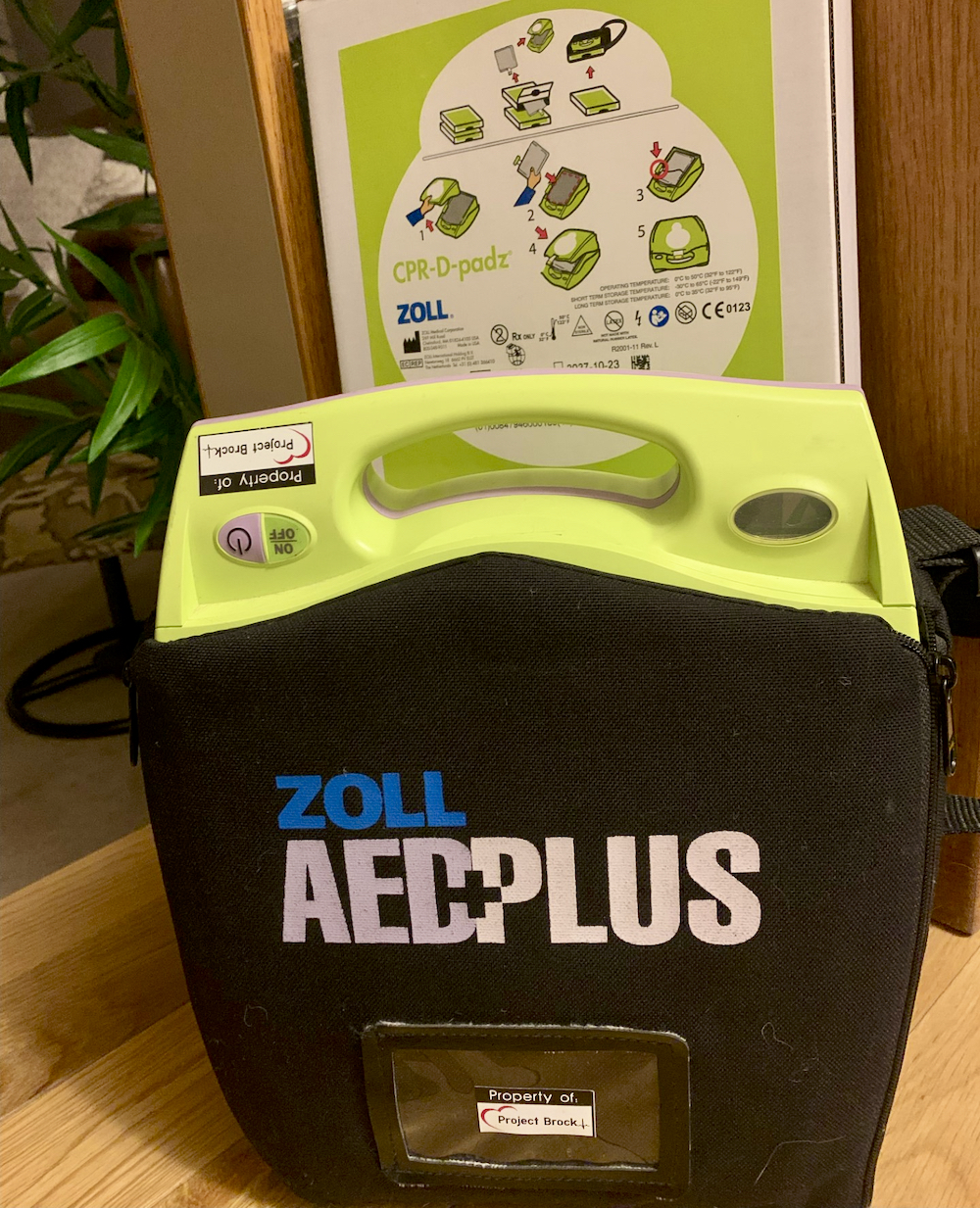

She lives on a farm near the Peace country town of Fairview and has made it a personal goal to get automated external defibrillators (AEDs) in every school in the province – particularly those in rural areas.

She wants to saturate Alberta and eventually the country with information on how to use them properly.

Read Also

Roots of Resilience: The 50-year evolution of Shipwheel Cattle Feeders

Alberta’s Shipwheel Cattle Feeders is one of Canada’s pioneers in holistic regenerative agricultural practices.

*“(Students) should be getting training and doing drills from the very earliest stages of elementary school all the way through school,” said Ruether, who runs the Project Brock Society, named in tribute to her 16-year-old son who, in 2012, died from heart disease in the middle of a school volleyball practice even though an AED was available but was not used.

She believes the odds of any kind of heart failure, including those among kids and teens, are too high to ignore the basic life support skills necessary to keep a victim alive until EMS arrives. The risks can be particularly high on farms and in rural communities.

“There’s been so many tragic accidents on farms,” said Ruether. “What if Grandpa became unconscious while he was, say, unloading the back of the grain truck?”

Brock was felled by a sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), which is not the same as a heart attack, although the terms tend to be used interchangeably.

According to the American Heart Association, sudden cardiac arrest occurs when the heart malfunctions and suddenly stops beating. Because it’s essentially an electrical problem based in the heart, it can affect anyone — even healthy, athletic kids and teenagers like Brock.

Although Canadian data is limited, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia says SCA claims the lives of more than 2,000 children and adolescents in the U.S. annually and accounts for approximately three to five per cent of all deaths in children ages 5 to 19 years.

“(SCA death in children) happens sporadically across the country: a death here, a death there that nobody really hears about,” said Ruether. She serves as a patient/family advocate on the Alberta Health Services EMS Science and Research Team, which is collecting cardiac arrest data in the province.

There’s a story behind every case. In Ruether’s case, Brock’s death is tinged with bittersweet memories.

“It was the Tuesday after the May long weekend and all of the kids were home,” she said.

“My two boys were there and the girls were home from college. We had a fantastic weekend. We went biking, dirt biking, and planted the garden.”

Ruether treasures that particular Monday because the next day couldn’t have been more different.

After school that day Brock asked his mom — worn out from work and weekend activity — if he could play the World of Warcraft online game with his friends. She responded by pointing out his lack of dedication to his math grades and forbidding his gaming plans.

Then Brock offered another idea.

“He was upset because I was mad at him and he said ‘well mom, would you like to come along (to volleyball practice)?’ I said no and said ‘if you don’t get your math marks up this will be the last practice you go to.’”

Those were among the last words she ever spoke to him and she’s regretted it ever since.

“I don’t know why I was such a (expletive) that day. I was just so grumpy and tired and miserable.”

Brock left for volleyball at about 6:50 p.m. At 7:25, Ruether received a distressing phone call. Brock had collapsed face-down and appeared to be breathing abnormally.

“His friends just thought he was joking around. One of his friends turned him over and tickled him and was just kind of joking around when they noticed that he was turning blue. And so they called 911.”

Although the AED was brought out, it wasn’t used because trained individuals, including EMS when they arrived, administered CPR to Brock.

Ruether believes Brock’s death could have been prevented if someone had used the AED as soon as he collapsed.

Those present likely didn’t know that Brock’s apparent abnormal breaths were actually agonal respirations. According to Web MD, agonal respirations happen when the brain is not getting the oxygen it needs to survive. It’s usually associated with cardiac arrest or stroke and demands the immediate use of a defibrillator.

“There’s an extremely high chance of survival if you’re shocked right away,” said Ruether.

“None of them were really informed about how critically important it is to apply an AED. And so it just sat there on the floor beside him while he died.”

Ruether holds no ill will toward those who did their best to prevent Brock’s death — especially since discovering the rarity of comprehensive AED training even among those with basic life support experience.

She admitted she probably wouldn’t have recognized Brock’s symptoms as agonal respirations herself, despite being highly trained in CPR and employed in a medical career, in her case diagnostic medical imaging.

“I didn’t know about agonal respirations. The 911 dispatcher didn’t know, so there were a lot of people who were just not informed about what they were supposed to do.”

Ruether didn’t know it at the time, but there was earlier evidence that Brock had heart problems that may have been ignored due to his age.

Brock had attended a drug and alcohol awareness program where he was twice hooked up to an ECG. Both instances resulted in an abnormal reading.

“They said there’s something wrong with the machine, ripped off the tracing and gave it to him. But I didn’t know that until a year after he was dead. Brock just went home and put that abnormal ECG in his little box of treasures and never said anything about it. So he had an arrhythmia that we knew nothing about.”

The experience taught Ruether that defibrillators and knowledge of how to use them were not as common as she thought. Using donations and a small group of volunteers, she set out to remedy that situation in Alberta’s six school areas.

“We put AEDs in all schools in the north area as well as at least one in every other area across the province,” she said.

“We have an Excel spreadsheet that we are working on to find all the schools in the province that have or do not have AEDs so that we can target AED placement in the remaining schools that don’t have any.”

As successful as Project Brock has been, Ruether said she needs help from the provincial government to ensure that AEDs are put in every school in Alberta. And she doesn’t intend to stop there.

“We need to have a commitment from the legislators that AEDs are mandatory in every school,” she said.

“Throughout the years we’ve trained thousands of students and teachers and citizens and health care providers, but it’s got to the point now where this is bigger than just a little project.

“I’m trying to find an administrator right now to take over the reins of the administrative duties and then help build it into a provincial and then national organization so that we can get this training throughout Canada.”

In the meantime, anyone interested in volunteering or donating to the Project Brock Society or learning what Ruether and company can do for a local school, school district, community centre or other facility, is encouraged to contact her at [email protected] or 780-835-1751.

*Update: the year of Brock’s death was updated. The Alberta Farmer apologizes for the error.