Achieving a 30 per cent reduction in nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer shouldn’t be a tall order for a crop sector or even individual farms, says a leader in 4R nutrient management research.

“Research across the Prairies has shown that it is possible to reduce emissions quite significantly without the need to drop the rate of N fertilizer,” Mario Tenuta said of the federal government’s goal to cut nitrous oxide emissions from fertilizer by 30 per cent by 2030.

And for the most part, farmers can reduce their emissions using well-established, well-researched management practices that don’t break the bank, said the University of Manitoba professor of soil ecology and research chair in 4R nutrient management.

Read Also

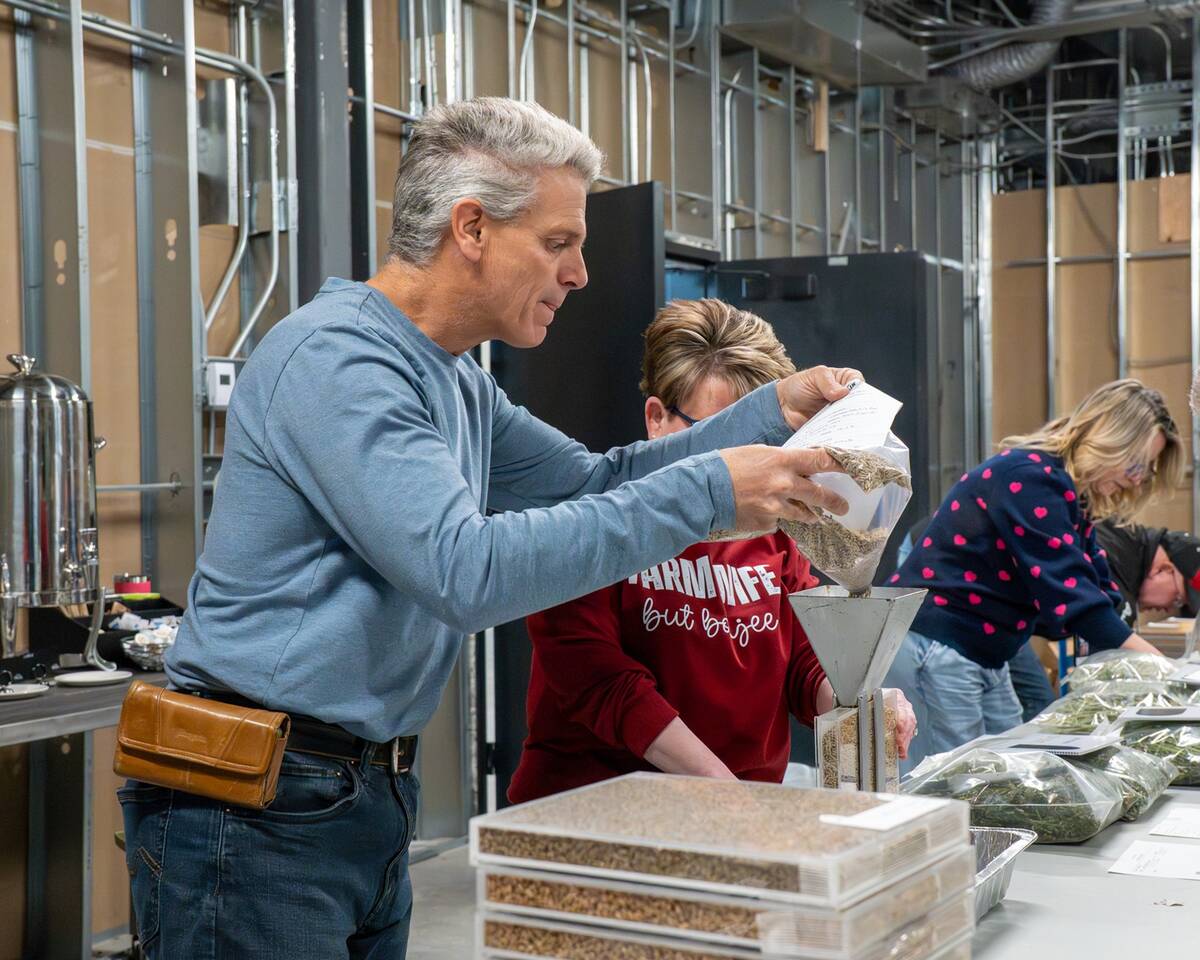

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“They’re practical actions that can be implemented by growers,” said Tenuta.

Nitrification inhibitors are one of the most effective — if not the most effective — tools producers have to reduce N2O emissions, he said. Although they can vary in effectiveness among individual products, they reduce emissions considerably.

“You can get anywhere between a 30 and 60 per cent reduction in N2O emissions with them.”

Growing nitrogen-fixing legumes is also a good bet for producers looking to reduce emissions.

“They will probably give you the most reduction, actually,” said Tenuta. “The emissions of nitrous oxide can be reduced by around 60 per cent under a pulse crop that fixes its own N. It’s pretty remarkable — they basically remove the N2O emissions associated with N fertilizer. Fertilizer emissions make up about 60 to 70 per cent of the emissions in a field.”

But it’s important to distinguish between nitrous oxide emissions from N fertilizer and the N2O emissions that are part of the natural growth process of the plant, said Tenuta.

“You don’t reduce those emissions because they’re in the background, they’re happening naturally.”

[PODCAST] Between the Rows: Emission deliberations

Another key practice is to limit fertilizer in unproductive areas or even leave them unseeded because less wasted N fertilizer equals fewer N2O emissions.

“Some areas of the field are more productive than others and your return on investment for nitrogen varies,” he said. “With depressions that are very frequently waterlogged, it may make more sense not to sow a crop in those areas.”

It sounds simple, and on an eyeball-to-action basis, it might be. However, farmers who want to make precision-based N management decisions will need a lot more data.

“You’ll need a combination of soil testing, yield maps and soil maps,” said Tenuta. “You can put these together and come up with a plan.

“Call it what you will, but a lot of people call it management zones where you partition the field into highly responsive zones where it pays to put on judicious amounts of fertilizer. And then there will be other areas where you put on less N because you’re just not going to get more yields.”

[RELATED] Grainews: Nitrogen fertilizer management to reduce nitrous oxide emissions

One reduction practice to approach with caution is split nitrogen fertilizer applications, where a portion of N is applied during the growing season.

This has become popular in some regions for its overall efficiency as well as its ability to minimize volatilization, denitrification and leaching. However, it doesn’t work everywhere and that includes a significant chunk of Alberta.

“That practice is not so practical in some regions, especially with short-season crops and areas that are semi-arid,” said Tenuta. “It’s quite risky to put fertilizer on mid-season if it never gets into the soil because you don’t get rains.

“In northeastern Manitoba it’s a really good strategy for reducing emissions, but in Alberta it’s probably only a good strategy under irrigation, not in semi-arid zones.”

Subsurface banding may become an important N2O-reducing practice, which is good news for many farmers because it’s one of the prevailing methods of fertilizer application on the Prairies.

Researchers have been comparing the practice to the broadcast-and-incorporate method. It’s been suggested that subsurface banding of three inches or more drives fewer N2O emissions.

“I still call that tentative,” said Tenuta. “I would like to see a few more field trials to get enough of a body of results that we can come to a confident statistical conclusion. It’s continuing.”