Peas, lentils and beans got a big boost in their public profile thanks to the UN’s International Year of Pulses in 2016 and soon rangelands will get their turn in the spotlight.

While “it’s tough to get people excited” about an event that’s still three years away, the UN International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists in 2026 is important because of the ongoing threat to this critical habitat, said the co-chair of the North American support group for the event.

“We’re losing native grasslands,” said Barry Irving, who was a long-time manager of the University of Alberta’s research stations. “We have all these wonderful programs and information but there’s still a ton of native grassland that is converted (to cropland) every year.”

Read Also

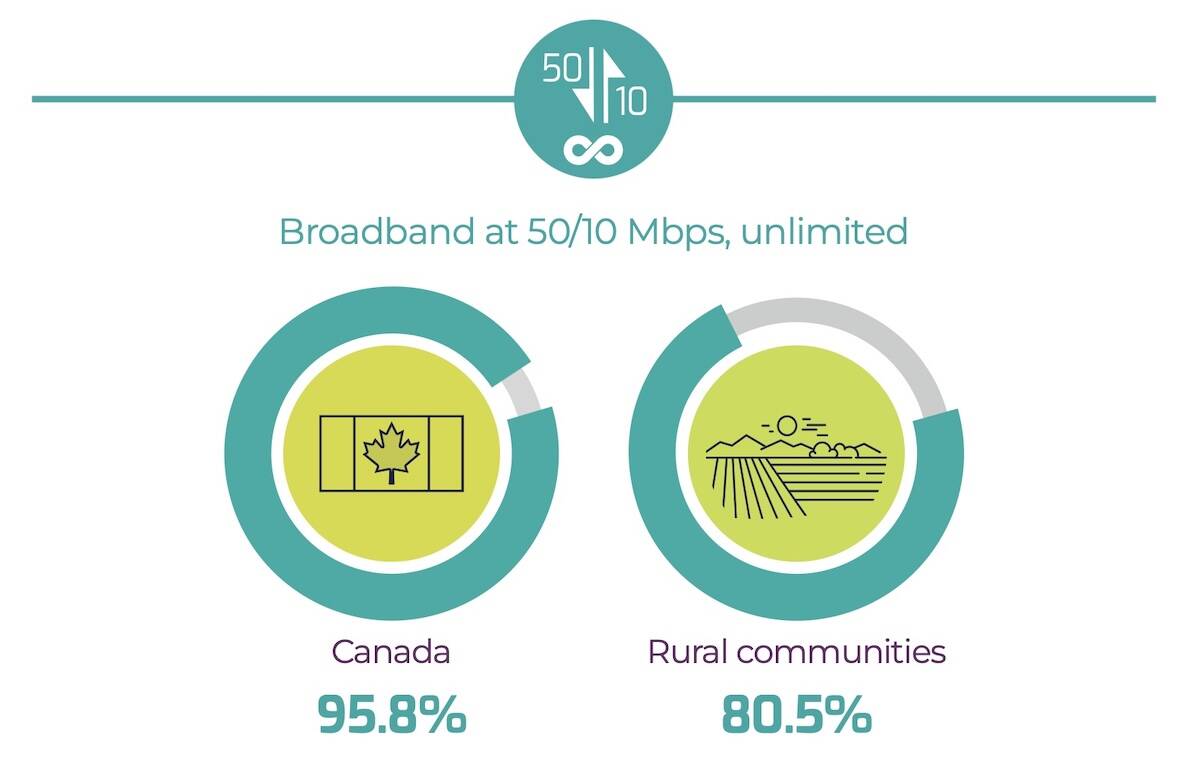

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

According to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, more than 70 per cent of the country’s prairie grasslands have been lost, and another 148,000 acres of native grasslands are plowed or developed every year.

More than 300 groups worldwide backed the idea of dedicating a year to rangelands and pastoralists (nomadic people who raise livestock in grassland environments).

“The International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists aims to raise awareness and advocate for the value of healthy rangelands and sustainable pastoralism, as well as advocating for the need to further build the capacity of and increase responsible investment in the pastoral livestock sector,” the United Nations said when it announced the event last year.

A lot could be accomplished by raising awareness of rangelands with people who rarely step foot on them — the urban population, said Irving.

“That’s the group that could have some effect on future arrangements.”

His group is one of 11 worldwide that are working on preparations for the international year.

“North America will take more of a focus on rangelands, but other places in the globe will take more of a focus on pastoralists,” he said.

Originally the focus was going to be on rangeland alone. Then planners realized pastoralists, who collectively care for an estimated one billion animals worldwide (from sheep, goats and cattle to camels, yaks and reindeer) also required recognition of their role.

When it comes to protecting rangelands, there are short- and long-term forces at play, said Irving.

“A balance needs to be had. When resources become limited, they become more valuable.”

Eventually, the value of rangeland will become high enough — through conservation program payments or long-term leases — to keep it native. Until that happens across North America, the conversion to cropland will continue, said Irving.

Some gains are being made.

In addition to the efforts of conservation groups, Ottawa created the On-Farm Climate Action Fund, which could help keep ranchers on the land, Irving said. There is also more messaging on rangelands to raise awareness of their importance.

However, the losses continue.

“Private land has no protection in Alberta,” said Irving. “We’re down to about 20 per cent native rangeland left (in some areas).”

Public land isn’t safe either, through occasional land dispersal auctions by government entities.

Irving said it is vital to make more people aware of what’s happening and its impact, adding that it’s not just the land that’s under threat.

“That awareness goes beyond the sustainability of land, it’s sustainability of culture, lifestyle, communities.”

Many individuals and groups worked to get the United Nations to declare an international year for rangelands and his group was very active, said Irving. There were about 50 people on the committee, which was loosely affiliated with the Society for Range Management headquartered in Kansas.

“We accomplish the unknown, which was getting the U.S. and Canada to sign on formally as endorsing the International Year of Rangelands and Pastoralists,” he said. Reluctance was based on a fear they would be asked to help foot the bill.

“Typically Canada, United States, European Union and Australia do not sign on to formally support international years.”

Getting the declaration was not a simple process.

The proponents first needed approval from the UN’s Committee of Agriculture (and getting on its agenda takes considerable time and effort) and then the proposal had to work its way up to the General Assembly, the UN’s main policy-making body.

In Irving’s view, it’s not what happens in the higher echelons of government and the UN that is key. It’s the actions in ranching and farming communities.

“It’s a grassroots movement, I think. It moves from the ranch or farm individual on up. Voice your concerns about converting (rangelands) to cropland within your community.”