For cattle, there is no escaping ticks and biting insects like flies. The herd spends all day and night in the pasture and are constantly exposed. It’s not just an irritation though. Bloodsuckers like ticks can carry and transmit anaplasmosis.

This is why researchers at the University of Manitoba and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada are examining the role arthropods play in anaplasmosis, as well as designing better tests.

“There’s a potential that it exists in cattle herds in certain parts of the country. So we want to get an idea of that, because until we have an understanding of some of those baseline risks, we don’t know maybe where to go, or if it’s really important to spend much time looking at this disease,” says Shaun Dergousoff, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Read Also

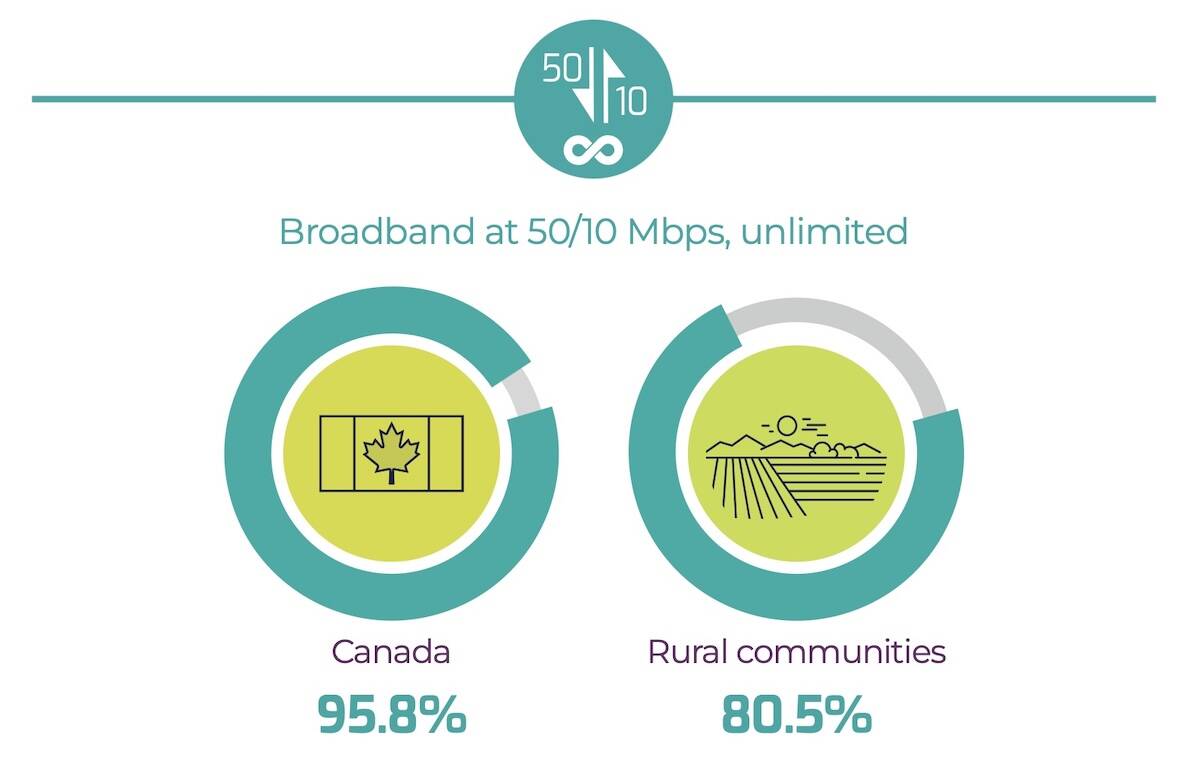

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

Anaplasmosis is caused by a bacterial parasite called Anaplasma marginale, which attacks the red blood cells. It affects cattle, sheep, goats and deer, but in Canada, it is more commonly seen in cattle.

Clinical signs of anaplasmosis include fever, anemia, weakness, weight loss and issues with breathing. It is rare for it to affect calves under six months of age and symptoms will be mild in calves younger than a year. It is rarely fatal for animals under two years old. In animals older than two years that have shown signs of illness, mortalities can range from 29 to 49 per cent.

Anaplasmosis is usually treated with an antibiotic, which helps with the symptoms but won’t get rid of the disease.

“Once an animal’s infected, it pretty much always stays infected, even if they’re not sick. But then the problem is they could become a source now of transmitting and moving that bacteria to other animals,” Dergousoff says.

Anaplasmosis is transmitted by anything that can spread infected blood, such as needles, dehorning tools, castration tools, etc. Biting pests also spread anaplasmosis. Arthropods well known for spreading anaplasmosis include the Rocky Mountain wood tick and the American dog tick.

Ticks and flies

Kateryn Rochon is an entomologist at the University of Manitoba and is working alongside Dergousoff on this project. She is focused on the insect side of the research, looking specifically at ticks and flies.

When it comes to ticks and flies spreading anaplasmosis, it is not really known how often it is transmitted from those sources, and how often from livestock management practices. That is part of Rochon’s work.

While ticks are known biological vectors, biting flies are not. However, they could still transmit the disease as a mechanical vector, which means the bacteria does not multiply inside them, but might be passed on from the blood around the fly’s mouth parts after feeding on an animal.

The question is whether they are transmitting the disease this way.

“We might not be able to find it in the ticks or the flies, but we’re looking because we’re trying to determine what role they play,” Rochon says. “For me, as an entomologist, there’s the interest of just what’s going on out there.”

To conduct this research, Rochon would collect ticks and flies in producers’ pastures. She’d collect ticks by dragging a white piece of flannel through the grass. This attracts the ticks because of something they do called questing, which is when they climb to the top of the grass and wave their claws in the air to latch on more easily. The light colour of the flannel attracts them.

Fly traps

They used two different types of fly traps for biting flies: horse fly traps and a Manitoba trap.

The Manitoba trap is an inverted canopy trap with a black yoga ball dangling below the canopy, and a container of some sort at the top. The ball attracts the flies into the trap because the colour and the gleam trick them into thinking it’s an animal. They then fly up, are caught within the canopy, crawl into the container and are trapped.

Rochon says this trap has been very successful, but sometimes, not even necessary.

“There’s some places where we go, there’s so many horseflies, we can just catch them with a net.”

During the summer of 2024, they caught over 1,300 flies at two different locations in Manitoba. After the insects were collected, they were taken back to the lab to be frozen and identified.

Then, after identification, each fly was dissected so their gut could be tested for the bacteria that causes bovine anaplasmosis. Since only females bite, they examine the flies’ ovaries to find out how many batches of eggs each female fly has laid. This is because each batch of eggs requires a blood meal. So, the researchers can see which species bite more, are more likely to spread diseases among cattle and at what point in the season.

This study will end in 2027.

A new anaplasmosis test

Alongside this research, another project is underway to create a reliable anaplasmosis test.

Currently, the diagnostic tests used for anaplasmosis are Giemsa-stained blood smears and serologic tests, according to Merck Animal Health. The bovine blood smear tests blood samples from the animal for the bacterial parasite that causes anaplasmosis.

Serologic tests are used to identify antibodies against Anaplasma marginale in cattle, which suggests past or present infection. These tests can help diagnose carrier animals who may be spreading the disease and not showing clinical symptoms, but it is not very accurate. The tests often misdiagnose anaplasmosis because the bacteria are similar to those from other diseases. This is why Dergousoff wants to make a more reliable, accurate test.

“A rapid test would be very beneficial, but also because some tests have had the problem where they’ve said that animals are infected with Anaplasma marginale, but it really was something else or not at all,” he says. “So they’re not perfect, and no test is, but we’re looking for an improvement.”

Dergousoff is working with beef producers and their veterinarians to take blood samples from their herd and test them for the presence of Anaplasma marginale. This will determine which animals are infected, even if they are not showing clinical signs of infection.

To create the new test, Dergousoff says they have to look closely at the molecules present and at the Anaplasma marginale bacteria.

Then, they will develop a method for testing and preparing the blood and start making a prototype for a device for blood testing. The goal is to create a device that can be used by producers so they can determine the health of their animals while doing other things, such as branding or vaccinating.

“It could potentially be simple enough for anybody to use and quick enough so that it can just be that chute-side rapid test,” he says.

They are working in areas of the country with the highest risk: Manitoba and south-central B.C. Manitoba was picked because of the historical context of the disease in the province. Southern B.C. was selected because they have seen misdiagnosed cases there.

“We don’t necessarily suspect that there will be Anaplasma marginale there,” Dergousoff says. “You can always be surprised, but they may be very useful samples to use in the development of our test if there’s a bacteria present there that’s very similar that we want to exclude from the test.”

The timeline for this project is less concrete — there are many things to accomplish before it can become commercially available. Dergousoff says he hopes to have a prototype in the next few years.

Anaplasmosis impact

Though anaplasmosis is a disease not many think about and was removed in 2014 from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s list of federally reportable diseases, it should still be on people’s radar.

“Sometimes the risk might be low, but also those things change over time. We’re seeing changes in the distribution of the ticks that can transmit this,” Dergousoff says.

Factors such as the number of ticks and flies are subject to change, which is why research like this is important.

Knowing about this issue is also important because that knowledge can help with prevention.

“Awareness is a big issue, because then we could take measures to maybe prevent these things before they become a big issue,” Dergousoff says. “So if we understand these things ahead of time, especially if we have a good, even better test … those kinds of things will help things from becoming a much larger issue over time.”

Rochon says while anaplasmosis isn’t currently an issue, that doesn’t mean producers shouldn’t be aware of what it is and what the effect might be.

“These little things can have an impact. And the little decisions sometimes can lead to problems that you don’t necessarily notice right away. And so I think being aware that this is something that is in Canada and might be becoming more prevalent, we don’t know.”

Dergousoff says they are currently looking for more producers in Manitoba and in southern B.C. to get involved in their research, to look at the risk and potential presence of anaplasmosis in the area. Data from B.C., specifically, would help them determine what other bacteria are confusing current diagnostic tests and eliminate them from their tests. There is financial compensation for involvement in the study.

If there is a positive test on an operation, researchers will notify the local vet and chief veterinary officer for the province. After a case of anaplasmosis is reported, the chief veterinary officer usually doesn’t require disease control measures. However, they may provide information and diagnostic support to help herd owners manage the infection and reduce the risk of spreading to other herds.

“It’s important to recognize these cases so we know what’s going on. But it’s also important to support the producers,” Dergousoff says.