Glacier FarmMedia – Regulations on gene editing of animals are fuelling negative public perceptions of the technology and stifling innovation in the livestock sector, according to an expert in animal genomics and biotechnology.

“I predict there’s going to be a targeted activist campaign against gene editing in food production for a number of reasons,” Alison Van Eenennaam of the University of California, Davis said during an online conference hosted by Farm & Food Care Saskatchewan earlier this winter.

The push-back against gene editing as a useful and viable science will continue to grow so long as it is considered synonymous with transgenic methods, said the veteran science communicator and extension specialist.

Read Also

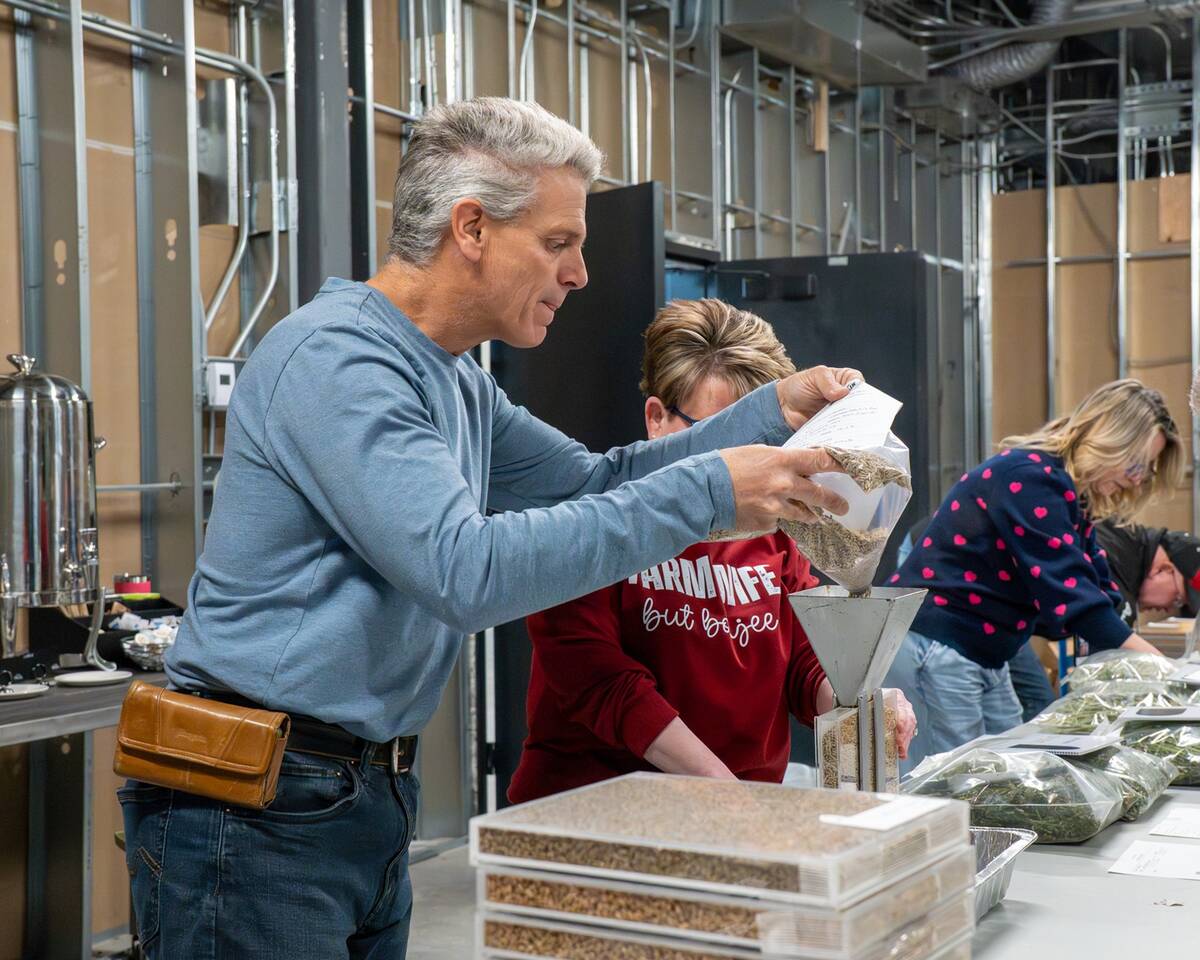

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

She cited the lengthy regulatory process in the U.S. and Europe that favours large companies that can afford to navigate the system — costs that can amount to tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. The AquaBounty salmon and GM corn varieties are examples.

The high cost eliminates smaller participants and having a sector dominated by large players stokes public skepticism, she said.

“I can’t spend more money burning cows than paying my students,” says Eenennaam, referring to the regulation-mandated practice of incinerating the carcasses of gene-edited animals (which are used in studies to how products from said animals are the same as non-gene-edited ones). The process of breeding, raising and testing milk and meat in her own research took six years, said Van Eenennaam.

Genetic technology development is also hindered by activist groups and special interest organizations, she said. The time involved in navigating government regulations gives activists more time to generate and spread misinformation about the technology and those who use it.

“I’ve heard the argument that regulation helps the consumer trust the product. I absolutely don’t buy that,” said Van Eenennaam.

“I think the regulation around genetic modification has made people more fearful than products which are not regulated. Like genomic selection for example, (which) dramatically changed the rate of genetic gain, does a lot of things genome editing does, but I haven’t heard boo around it.

“Genome editing being unique and requiring a higher bar, it’s going to make it a target.”

Given the pressure from activist groups, Van Eenennaam said she wonders whether enough people in the scientific community will stick their necks out for gene editing.

“Why would I do that for gene editing if I can’t afford to use it in my own lab?”

She argued gene editing supports a variety of other technologies already used in the livestock sector, such as artificial insemination, embryo transfer and genomic selection.

Though her professional focus is cattle, she highlights “glow fish” as an example of technology fully accepted by consumers.

The brightly coloured aquarium fish, genetically modified to be fluorescent, make up 15 per cent of the aquarium fish market, she said, adding they bypassed many regulatory steps because they were deemed to have no environmental or human health risk.

On the other hand, if allowed, gene editing could produce pigs resistant to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, tuberculosis-resistant cattle, lighter-coloured and more heat-resistant dairy cows, removal of allergenic milk proteins, and more breeds of polled cattle.

“To me genetic improvement which is permanent and passed on from generation to generation is a better solution… than actually having to treat animals that are sick,” said Van Eenennaam.

“We’ll be able to introduce useful alleles without linkage drag, and bring in novel genetic variations from other breeds, like polled into Holstein.”

But that will require having “a risk-based, product-centred regulatory approach,” she said.

“We need to discuss the opportunity lost of not using these technologies.”

Matt McIntosh is a contributor to Farmtario. His article appeared in the Dec. 13, 2021 issue.