It’s the stuff of stars, lightning bolts, and the aurora borealis — and now, Alberta researchers are finding uses for plasma a little closer to home.

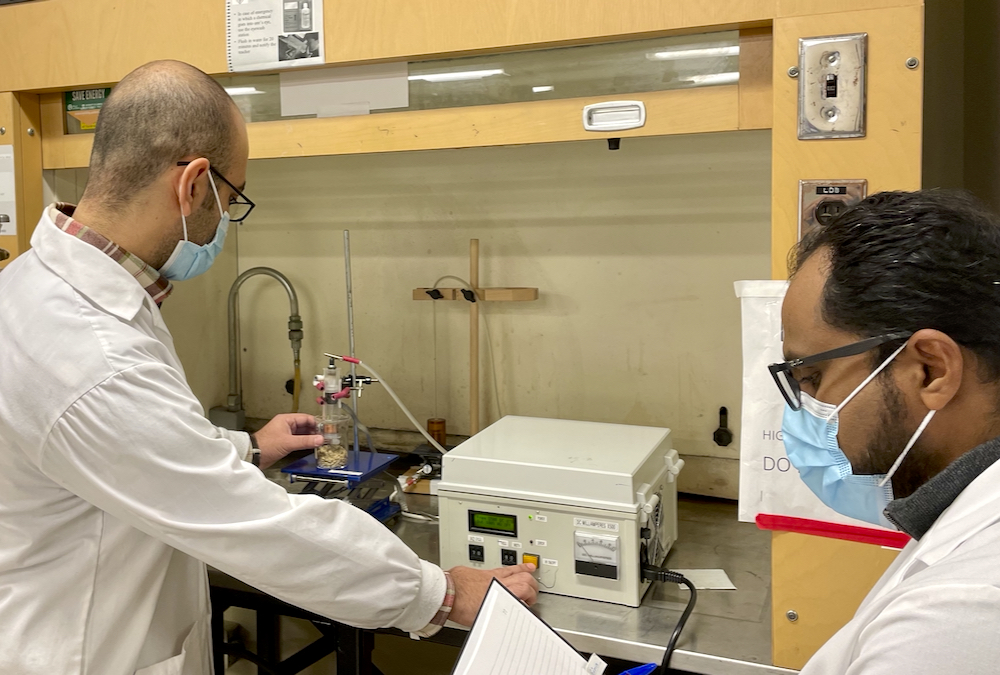

“There are so many applications for plasma in agriculture,” said M.S. Roopesh, assistant professor of food safety and sustainability engineering at the University of Alberta.

“We have been doing a lot of research on the various applications, like improving food safety by reducing the micro-organisms and pathogens in different types of products.

“These products can be contaminated with bacteria, fungal pathogens, or mycotoxins. But if we can commercialize this technology, farmers in Canada can make use of it for decontaminating their products.”

Read Also

Lethbridge research farm lease renewed for 20 years

Lethbridge Polytechnic and the Government of Alberta have signed a 20-year renewal of a land lease agreement for the institiution’s research farm.

While we usually think in terms of something being a solid, liquid or gas, plasma is the fourth state of matter. Researchers at the university started looking at uses for cold plasma for food and ag applications more than five years ago. And what they’ve found so far is that plasma contains highly reactive components that can deactivate or reduce micro-organisms on the surface of grains, meats, produce, and other food products.

“Several of these products are associated with a lot of food safety issues due to the presence of pathogens like salmonella, E. coli, and listeria,” said Roopesh. “It’s not just in Alberta — it’s all over the world.”

The cold plasma, which is created at low temperatures, can decontaminate these food products in a safe, environmentally friendly way.

“It doesn’t use any chemical sanitizers that are commonly used in the food industry,” he said.

“When you create plasma, you have all these reactive species, but once they’re done their process, they go back to their original state. They don’t leave any residues.

“(So) when using plasma, we can possibly reduce the use of these chemical sanitizers.”

The process itself is also more sustainable.

“What you need is basically a gas medium and an energy source to convert the gas into plasma. We use electricity to convert gas into plasma, so it’s more of a clean process.”

As part of this research, Roopesh and his team have been looking at the effects of plasma on different mycotoxins that cause problems in Canadian agriculture, including deoxynivalenol (or DON).

“We did some work on barley and wheat, and we found that when we used pure mycotoxins, we got very significant reductions in mycotoxins in a short period of time by the plasma treatment.”

When inoculating these mycotoxins on barley and wheat grains, the plasma treatment reduced levels by 54 per cent.

“Because some of these mycotoxins are really resistant to other types of treatments — for example, heat treatments — we found more reduction in the mycotoxins by plasma treatment than those other treatments.”

The treatments worked even better on bacteria.

“There we found more than 99 per cent reduction in several pathogens — like listeria and salmonella — in poultry meat and fresh fruits.”

Improved germination

A side-effect of these plasma treatments is a change to the physiology of grains and seeds, and that’s led to another application for cold plasma — improving germination.

“When you treat a seed with plasma, you can change its surface properties, and that can lead to improved water absorption, which can improve germination,” said Roopesh.

“When we looked at the germination of wheat and barley seeds, we found a 10 to 13 per cent improvement in the germination of these seeds. That’s very significant.

“This is a current research area, so we’ll know more about that in the future.”

But as with any new technology, “nothing is perfect.”

One of the potential difficulties is that using cold plasma (either to sanitize or improve germination) could affect food quality.

“Plasma contains these reactive species, and they can interact with the product,” said Roopesh.

“We haven’t seen a lot of quality changes, but there can be quality changes in the product depending on the type of product you’re using and the type of plasma you’re using. That’s a challenge we’re going to need to think about in the future.”

The next challenge is optimizing the process to make it more effective and more efficient.

“You need to create plasma in an environment where it is more or less uniform to ensure you have uniform exposure of plasma to the product. That’s an engineering challenge.”

And finally, there’s the scaling up of this technology.

“How do we treat a large volume of grains or other food products? If we wanted to treat tonnes of grains by using plasma, how can we actually scale this process up?” he said. “We’re looking at commercializing this plasma technology for food safety applications. We believe that can happen in Canada, so we will be looking for opportunities to translate this knowledge to the industry and farms.”

That’s ultimately the goal of this research, Roopesh added.

“We want to take this technology to the farms and fields and other industries,” he said. “We believe that this technology has great potential, and we’re currently looking for collaboration with farmers and industry associations to explore the opportunities for this technology in food and agriculture.

“This is a new emerging technology, but we have a lot of belief in it.”