Glacier FarmMedia — It’s hard to know where to begin when telling the story of beavers.

One starting point is purely ecological, looking at their singular adaptations and resulting impact on their local environment. Another has more to do with humans and the evolution of Canada itself, which is appropriate for an animal that has become our national symbol.

Why it matters: Beavers aren’t the most popular mammal among farmers or municipalities thanks to their impact to infrastructure, but their ecological and behavioural quirks make them undeniably unique.

Read Also

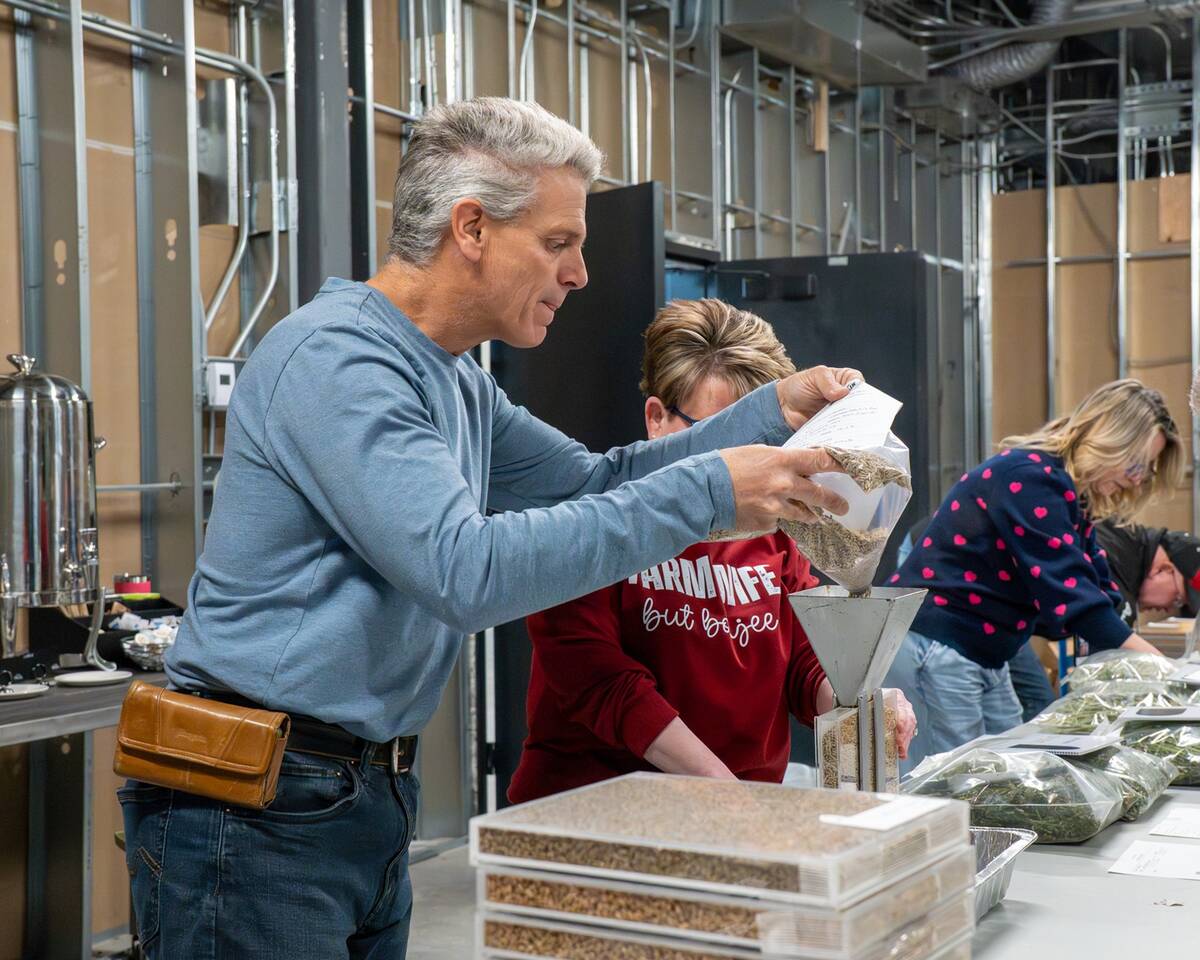

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Reaching weights of up to 25 kilograms, the beaver is the second-largest rodent in existence. Mammalogists believe that beavers share common ancestors with modern-day rats and gophers.

Having evolved to a semi-aquatic mode of living, they’re poetry in motion while in the water, but relatively slow and clumsy on land, making them vulnerable to predators like bears, wolves, coyotes and cougars.

They have also earned their reputation as relentless construction engineers.

Ecologists have a few terms for species that have especially large impacts on their habitats. Bison, for example, are called a keystone species for grasslands because of the way vast herds that once roamed the region disrupted vegetation. Over time, that activity caused ecological communities to evolve in response.

Animals that directly cause a significant physical change to their environment are called ecosystem engineers, and beavers are perhaps the best example of an ecosystem engineer on the planet.

Beavers are the only animals that can both cut down trees and build dams. These efforts lead to more diverse plant and wildlife communities in the new habitat they help create. When local watersheds that boast beaver ponds are compared to similar catchments without beavers, we usually find more fish species and larger riparian areas that attract more amphibians, reptiles, birds and grazing animals.

Over time, creek valleys themselves can flatten out from a buildup of sediments. Areas of grass and low shrubs develop, often called “beaver meadows,” and become an important forage source for grazers like moose and elk.

All this engineering improves beavers’ access to food, keeps ponds from freezing to the bottom and creates security from predators.

Urge to build

The sound of running water is a major cue for beavers to build dams. In both captivity and the wild, it’s been found that placing a speaker playing that noise in the vicinity of beavers can induced them to start building against the speaker.

Dam building starts at a constriction in the creek or waterway. Lengths of sticks are laid down, with the bigger ends pointing upstream. As the growing pile starts to slow the flow, more sticks, logs, mud and rocks are added.

As the water level rises, so does the height, mass and length of the dam. Eventually, the effort to go bigger is simply too great, and the beavers switch to repairing any leaks that could threaten the structure.

The biggest recorded dam, found a few years ago in Wood Buffalo National Park, measured 850 metres – twice as long as the Hoover Dam — and had an estimated 70,000-cubic-metre water storage capacity.

Water retention

Having many beaver ponds in a catchment brings a similar result as what humans seek through modern watershed management. They are slow-the-flow features in watersheds. They reduce peak flows during high water, while holding water back and maintaining volume when water levels drop.

Leaks from the dam supply water downstream during low water periods. Beaver ponds can also raise local groundwater levels. Some of that volume then slowly seeps back into the stream. Slower flows also reduce the amount of sediment carried downstream.

Keeping house

Beaver houses are either built into a riverbank or isolated in open water. Riverbank houses start with a burrow running up from below the water line. The structure then grows with the addition of sticks and mud. Open water houses have a base sitting on the bottom of the water body, building up until the pile reaches up to two metres above the water line.

Living quarters are hollowed out above the water line and are large enough for a family group (usually five to seven animals) to rest, rear young and feed. Come fall, houses are covered with a thick layer of mud to seal them from the elements and reduce predator intrusions. Additional bank holes are excavated around the pond and serve as back-up hiding spots and feeding sites in winter.

Beavers may also dig canals to connect otherwise isolated, low-lying areas. I’ve seen these reach up to a metre wide and a half-metre deep, large enough to float sticks and evade predators.

The most unusual such excavation in my experience was spotted during a drought year in a western Manitoba wetland. The colony had built a house into a dugout on one shore but were cut off from their feed source (an aspen fluff across the way) by the exposed marsh bottom.

There was no water access to be found. In response, this bunch excavated a 100-metre canal through the muck. This filled with water, making an efficient route to their lumbering area.

Full-season menu

Like ruminants, beavers have gut microbes that break down at least some of the cellulose they take in. Beaver excrement in the water is said to look like a line of fine sawdust.

Beavers eat soft vegetation like pond lilies, grasses, reeds and sedge roots and shoots during the growing season, but also turn to the bark and shoots of deciduous trees year-round. With trees and shrubs providing both food and construction material, beavers can spend countless hours cutting down and hauling branches and smaller tree sections to their pond.

Doing this work at night reduces their exposure to predators.

With large, self-sharpening and ever-growing incisors, beavers can chew through a tree with a 15-centemetre diameter in under an hour. They will also take on trees over 30 cm in diameter, which can take many hours. They may have little use for the thick trunk, other than to eat the bark, but larger branches end up in dams and houses. Smaller shoots are also eaten.

Securing a winter food supply is a key autumn chore. Feed piles of fine, green branches are built up beside a house, where they can be quickly accessed from under the ice.

The ice and snow of winter locks beavers into a watery world. During my trapping days, I learned that beavers gain body fat through the winter, suggesting that the animals have a largely sedate winter lifestyle as long as the food holds out, water levels don’t drop and no marauding otters make an appearance.

Winter studies have uncovered yet another beaver oddity with the lack of sunlight to govern their schedules. They may abandon a 24-hour activity cycle and end up with a “daily” cycle that’s up to 29 hours long.

A family affair

Beavers mate in winter and up to four kits are born by late spring. The kits are fully furred and eyes are ready to open at birth. The new kits then join a group that often includes siblings born the previous year or even older. Those first-year kits have the year off, while older family members take on tree-felling and construction tasks.

By two years of age, most beavers will strike out in the spring to seek mates and establish new colonies. These vagabonds are vulnerable to predators, as well as getting chased away from established colonies.

As watersheds get filled with beavers, they may settle into marginal sites like ditches and artificial ponds. Such locations don’t work that well for beavers, and their presence there isn’t great for us either.

Beavers and people

There is one species of beaver in North America and a similar one in Eurasia, and beavers show up in stories, legends and myths on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

In North America, beavers are prominent in the stories of Indigenous people, highlighting their importance as a source of food, clothing and inspiration.

With the arrival of Europeans came the flurry of the fur trade. As most of us learn in school today, demand for beaver pelts was one of the driving factors for the expansion of European settlers and underpinned the events, economic changes and tragic upheavals to Indigenous ways of life that characterized centuries of our country’s history.

As a new fur-trade economy developed, Canada’s first homegrown currency of sorts, the Made Beaver, was developed. The Hudson’s Bay Company found it necessary to devise a unit of value (one prime beaver pelt in good condition) to facilitate the bartering process and keep the accountants happy. Prices offered for all species of fur and the value of all goods traded were set in Made Beaver. In time, HBC issued brass tokens in various denominations of one Made Beaver.

The first Canadian stamp, issued by Canada’s fledgling postal system in 1851, was the “Three-Penny-Beaver,” an early recognition of the esteem with which beavers were held in the hearts and minds of citizens.

But recognition on a stamp did not make up for the relentless pursuit that, by 1900, had eliminated or significantly reduced beavers across the continent.

That assault was not as complete as it was for passenger pigeons or bison. Decades of strict conservation and restocking programs led to an epic population comeback across the continent in the time since.

Living with beaver

Continental beaver numbers may exceed 20 million today, an amazing number considering they were barely hanging on a century ago, but are still well below pre-European populations. Large areas of the continent are now too developed to support beaver. Where we do have beaver habitat, local populations are often approaching carrying capacity.

The same behaviours that make them so interesting from an ecological lens have also fostered conflict with human neighbours.

In 2011, Canada’s national animal got slagged during a Senate speech. It was described as a “toothy tyrant” and a “dentally defective rat” that wreaks widespread havoc.

Rural landowners and municipalities, facing beaver-caused flooded roads, washouts, plugged culverts, tracts of downed trees and ruined fences, can’t be blamed if they agree with the sentiment. The cash costs and transportation headaches from beaver busywork is not small.

While we can roughly estimate the impacts of beavers from environmental and economic perspectives, their importance to Canada’s history, development and sense of identity is a much harder calculation.

Regardless of that computation, and any irritation that landowners might feel when a family of beavers move in, those impacts are more than sufficient to justify the beaver’s recognition as Canada’s national animal.