A modern broiler chicken grows a whopping four times faster than one bred in the 1950s — and packs on those pounds with much less feed.

“They’re much more efficient,” said Martin Zuidhof, associate professor poultry systems at the University of Alberta. “It takes half the feed to grow a bird.”

Zuidhof has been getting lots of calls from reporters since he and fellow researchers from the University and Alberta agriculture published a study on chicken breeding in the journal Poultry Science. The researchers raised three types of commercial broilers — the first group was from a strain developed in 1957, another from 1978, and the third was a modern commercial variety developed in 2005.

Read Also

Canada needs presence to break into Asia-Pacific trade: speakers

Canada wants trade in southeast Asia, but experts say more focus, commitment and consistent presence in the ASEAN region is needed.

- More from the Alberta Farmer Express: Community comes together to save rare chickens

All three sets were given the same feed and raised under identical conditions — but the end result was dramatically different. After 56 days, the scrawny ’57 model weighed 905 grams and while the ’78 version was double the size, it still looks puny compared to the 4.2-kilogram modern bird.

All three sets were given the same feed and raised under identical conditions — but the end result was dramatically different. After 56 days, the scrawny ’57 model weighed 905 grams and while the ’78 version was double the size, it still looks puny compared to the 4.2-kilogram modern bird.

“We also took some pictures and that’s one of the reasons why this study has become fairly popular,” said Zuidhof.

Not surprisingly, some thought something untoward was behind the growth spurt.

“The subject of hormones has come up a couple of times, and we can honestly say that the only thing that was different in this study was genetics,” said Zuidhof. “We didn’t feed them hormones. This is decisive evidence that it’s not hormones — it’s genetics.”

The media inquiries have given the professor a chance to explain the basics of livestock breeding, and why chickens have changed so quickly.

“The chicken is like the drosophila (fruit fly) of the livestock industry,” he said. “If you want to see genetic changes quickly, you choose a model that has a short generation time and lots of progeny. The chicken isn’t a fly but on the spectrum of livestock, the chicken is the most fruitful.”

Actually, the seeds of change were planted more than 70 years ago when American grocer A&P began holding “Chicken of Tomorrow” contests to spur development of a meat chicken at a time when most broilers were culls or spent layers.

“Traditionally, they were grown for eggs and at the end of a laying cycle, you’d stew a chicken in a pot and you had a little bit of meat from it,” said Zuidhof.

A number of farmers entered the contest, selecting and breeding their biggest birds. That led to modern breeding programs with the emphasis on growth rates and feed efficiency. The short breeding cycle made for rapid gains, said Zuidhof.

“You get a fast-growing chicken that has 120 progeny (in a year). If it’s a male, closer to 1,000. You can multiply your best genetics over a lot of progeny, from which you then select from again.”

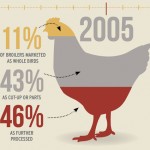

That’s not only led to bigger birds, but ones that suit the market. Breast meat now accounts for 20 per cent of live body weight versus just 11 per cent a half-century ago.

A wave of consolidation left just two big chicken breeders (Cobb-Vantress and Aviagen, both headquartered in the southeastern U.S.). They still select for growth, yield and efficiency, but also for qualities like leg strength and resistance to metabolic disorders, which has made today’s chicken quite robust and with a lower mortality rate, said Zuidhof.