At first glance, grazing a pasture may appear as simple as placing cattle in a fenced area with a water source. However, practising effective grazing management is an art and a science.

Pasture conditions and types vary widely from native grassland to tame forage, with stands comprised of many diverse plants or perhaps just a simple mixture of a few grass or legume species. Regardless of the pasture type, focusing on a few key principles can help maintain forage productivity, ensure stand longevity, sustain a healthy plant community, conserve water, and protect soils.

Read Also

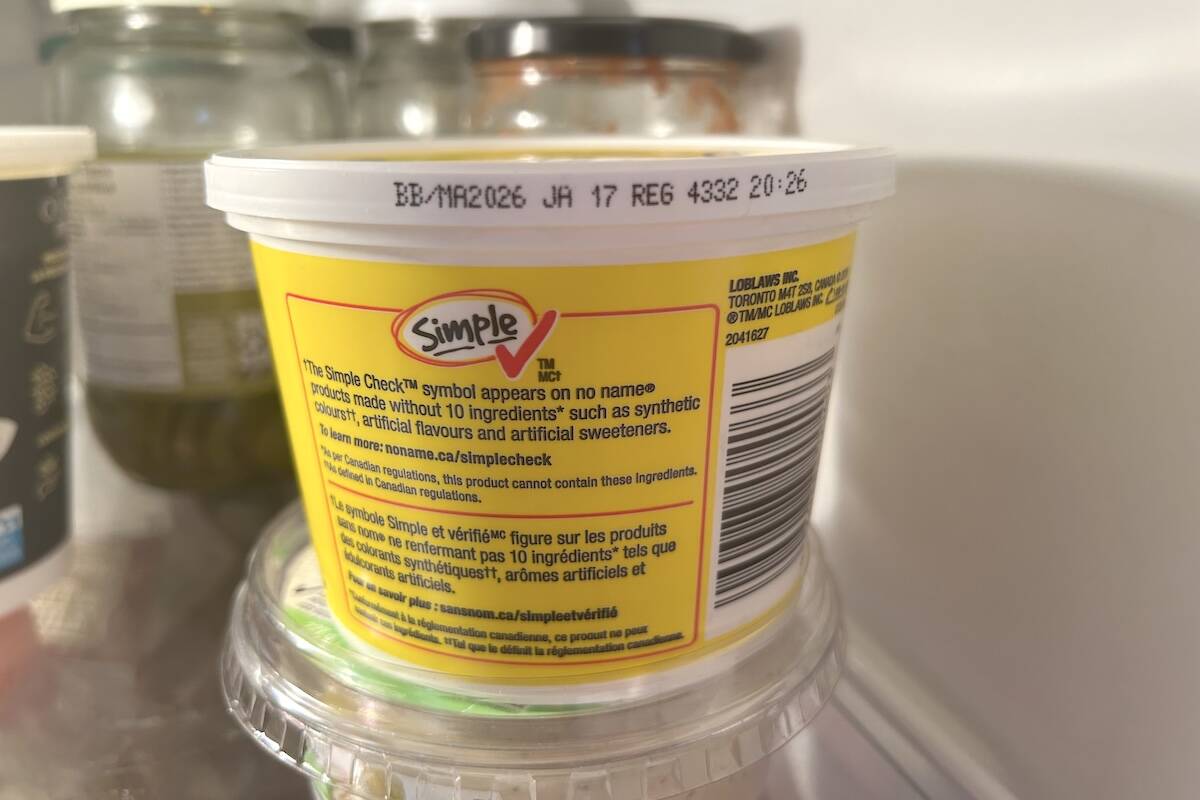

Best before doesn’t mean bad after

Best before dates are not expiry dates, and the confusion often leads to plenty of food waste.

Here are four main factors to remember:

Balance forage supply and livestock demand

Avoid overstocking by ensuring there is adequate forage available for the number of cattle, and the length of time, the cattle will be grazing. The Carrying Capacity Calculator (available at beefresearch.ca) can help determine a starting point for stocking rates. In addition to grazing, remember to factor in a utilization rate to account for trampling, wildlife, or insects. General guidelines for native pasture suggest a utilization rate of 25 to 50 per cent, and for tame pasture a utilization rate of 50 to 75 per cent is a built-in buffer that allows the pasture to sustain itself.

Distribute grazing pressure

When left on their own, cattle will prefer to graze moist, productive areas of a pasture and avoid dry hilltops. But they can be managed to graze a pasture in a relatively uniform manner using different methods. Temporary or permanent fencing, placement of salt and mineral, and stock water locations can all be strategically manoeuvred to effectively move cattle. Working with available resources is important.

Provide rest to help plants recover

Forage plants need to replenish their energy reserves and prepare for the next grazing event. If they don’t have adequate time to recover, pasture productivity can dwindle, and pastures can become susceptible to weed infestations, soil erosion and winterkill.

Avoid grazing during sensitive times

Grazing too early can set a pasture back for the whole season. A general rule of thumb is for every day grazing is deferred in the spring, you gain two days of grazing in the fall. Other situations such as grazing wetlands or species-at-risk habitat, may benefit from deferring grazing until nesting season is over or flood potential has subsided.

Pastures should also be managed to retain adequate ‘litter’ cover. The dead or decaying plant residue left from previous growing seasons is a valuable resource in both tame and native pasture stands. Litter insulates the soil, keeping it warm in the winter, and cool in the summer. As it breaks down, litter provides nutrients to the surrounding plants, and reduces soil erosion and water loss due to evaporation.

There are many different types of grazing systems promoted by groups and individual producers, including, but not limited to, rest-rotation, AMP (adaptive multi-paddock), intensive, or strip grazing. While each system has its own benefits and drawbacks, almost all systems factor in the four key principles of grazing management. By carefully managing pasture as the valuable resource that it is, forage production and range health can be sustained for this season, and for many years to come.