Food banks across the province, including those in rural communities, are seeing soaring demand.

“Food bank use in Alberta has gone up 73 per cent since 2019,” said Arianna Scott, CEO of Food Banks Alberta.

That’s more than double the 35 per cent rise seen nationally over the same period, but it is no surprise to those on the ground in rural Alberta.

Read Also

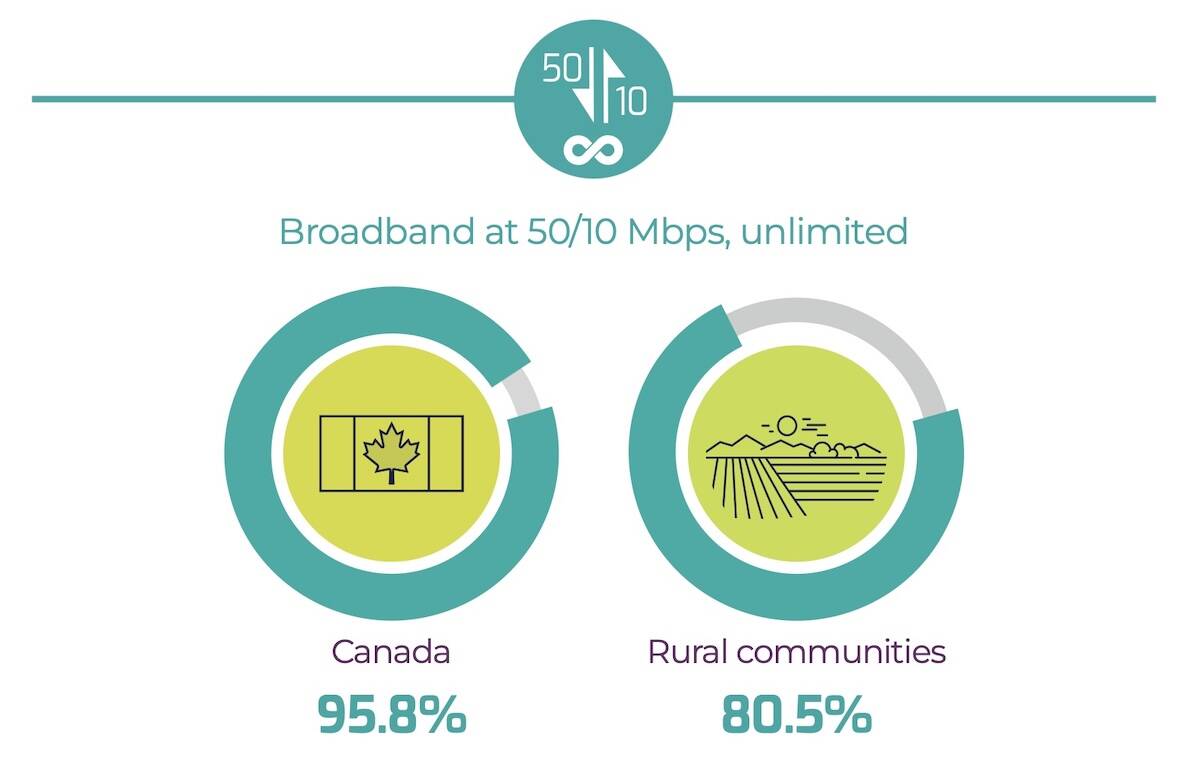

Rural Alberta gets further boost to internet connectivity

The province and feds join forces to help remote/rural Albertans get connected to reliable high-speed internet through its Broadband Strategy.

“Our March numbers from 2021 to 2022 went up 83 per cent – from 195 people to 358,” said David Carter, executive director of the Lord’s Food Bank in Rocky Mountain House.

“Our community is just over 6,000 people now. That’s a pretty significant percentage of our population using us.”

It’s clear what’s behind the higher numbers: a big jump in the cost of living.

“A lot of these people are people that you would not expect to show up in a food bank in good times. A lot of these people are quite embarrassed to be coming,” said Carter. “We work through things in the intake, and people have three to four different things – the cost of food, cost of housing, cost of utilities, all of those things.

“It just all hits at once.”

About 20 per cent of food bank users in Alberta are employed and 11 per cent are homeowners. Nationally, those numbers are 14 per cent and seven per cent, respectively. But with prices rising so quickly, people can’t make ends meet.

“The price of everything (from 2021 to this year) has increased exponentially,” said Scott. “While many people have gone back to work, they have gone back to work for less pay than they were making prior to COVID-19. We’re finding an increased number of people who are working and accessing food banks.”

Alberta food banks saw more than 155,000 visits during the latest one-year period ending in March, when the annual nationwide ‘hunger count’ by food banks is conducted. The latest surge in numbers is not the first.

In Parkland County, food bank use soared during the recession of 2014-15.

“We saw a drastic increase in families coming to our doors,” said Sheri Ratsoy, executive director of the Parkland Food Bank. “That hadn’t quite stabilized yet when we found ourselves in the recession in 2019.”

The number of people visiting the food bank did fall during the pandemic after Ottawa rolled out the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, better known as CERB, but that program ended in May.

“For our fixed income families, that was an opportunity to earn more than they had on income support or disability income,” said Ratsoy. “Once the CERB payments ended, we saw an increase overnight. “And now, with inflation, we’re up about 30 per cent over (this time last year).”

In 2017, the Parkland Food Bank, located in Spruce Grove, distributed just over 7,300 hampers. This year, it is already up to more than 9,000 hampers.

It has a database that uses blue dots to mark the general area where clients reside, and they are spread across the county.

“It (food insecurity) is something that affects every single neighbourhood in Spruce Grove, every neighbourhood in Stony Plain and a lot of different communities in Parkland County,” said Ratsoy.

“People have something in their head of what a food bank client would look like. The little blue dots really challenge that. It can be anybody in any neighbourhood that is in a situation that is unexpected, and they are struggling financially with that situation.

“That could be a cancer diagnosis, a broken leg or unemployment. Things happen all the time with our clients.”

One-fifth of rural food bank users in the province are seniors and people with a disability. Almost 45 per cent are families, with children accounting for one-third of the visits.

There’s also “a much higher level of working people” who now need food assistance, “people working full time, sometimes multiple jobs, and still unable to keep up with the cost of living,” Ratsoy added.

Many are affected

“There’s really no wiggle room,” he said. “They go to the grocery store and things are up in price significantly, and it’s just too much. They can’t do it.

“So they end up not getting enough food or substituting with things they don’t like.”

Carter has been with the food bank, which serves Rocky Mountain House and nearby communities, for 11 years and has seen people “graduate,” only to return recently because of the rising cost of living.

“Any gains they have made are lost by inflation and other issues right now,” he said.

The organization got a surge of volunteers during the pandemic, people who were tired of being stuck at home “and wanted to be doing something.” But most are over the age of 60 and Carter has noticed that some have picked up part-time work to pay their rapidly rising household bills.

Single people are the largest group of food bank users (roughly two in five in Alberta), which is only to be expected, said Ratsoy, because “it’s a lot harder to maintain household costs than if you’re a couple with dual incomes.”

Some of those single people are seniors who are newly widowed.

“If you’re a senior who has lost a spouse, and especially if you’re a female who has lost a spouse and she loses that full pension from that spouse, it’s a lot harder to maintain your property and your cost of living every month,” she said.

Those living in rural areas face additional challenges, both Ratsoy and Carter said.

“People will tend to move out to smaller, rural communities where rents are cheaper but they don’t realize the higher cost of living that comes in those more isolated communities. You’re paying more for groceries and for gas. Everything is that much harder to access,” said Ratsoy.

Parkland Food Bank has a delivery program for clients in Spruce Grove and Stony Plain, and works with another delivery program for acreages, but the latter can present challenges.

“There are safety considerations when you go out to somebody’s isolated home,” said Ratsoy. “We have some clients who are living in very different situations in the rural communities where you might have five or six people staying in one property, in various means of housing with absolutely no transportation.”

People often carpool and “get as much done as possible” while they’re in town, said Carter. But even those who live in Rocky Mountain House struggle because there’s no public transportation other than taxis. Those with cars have to think twice about every trip they make.

“There’s definitely transport issues for people, especially when gas was so expensive,” he said.

Pulling together

“It’s basically a grocery store or shopping model,” he said. “That’s been really good. The food is more efficiently used because people are only bringing home things that they want. So we’re not buying a bunch of canned beans if no one wants them, for instance.”

People are given an allotment based on their family size and can pick items according to their preferences.

The change was made one year into the pandemic.

“We could see the writing on the wall that the demand was going to be increasing and so we wanted to be more effective with the help we could provide,” said Carter.

“Pre-COVID, everyone got the same stuff. If we didn’t have beans, I had to run out and buy beans, to make sure they went in the hamper. Our food purchasing has gone down, even though our food demand has gone up.”

The Lord’s Food Bank has also set up Little Red Pantries around town, which are filled with canned goods that people can take.

“There are people who are too shy to come in or they’re not comfortable calling us,” he said. “This can help with emergency needs or with people who have missed our hours or are homeless. We’re trying our best to make sure people always have something to eat.”

But the simple math is that when demand increases, so must donations.

“It’s never been more important that we focus on ensuring that services that provide basic needs as sustainable and supportive,” said Scott.

Parkland Food Bank has been getting more donations and although demand is rising even faster, the organization is grateful, said Ratsoy.

“We really appreciate the support that the community gives us,” she said. “We couldn’t meet the need of the community without them.”

Carter said he wants people to know they shouldn’t hesitate to go to a food bank when they need to.

“We really need to pull together, as communities and as people, to get through this,” he said. “Part of that means being attentive to our neighbours and being willing to step in and offer to help before it becomes really dire.”

Food Banks Alberta has 107 members. An interactive map showing locations and contact info for each of them can be found at foodbanksalberta.ca (click on the Find A Food Bank link).