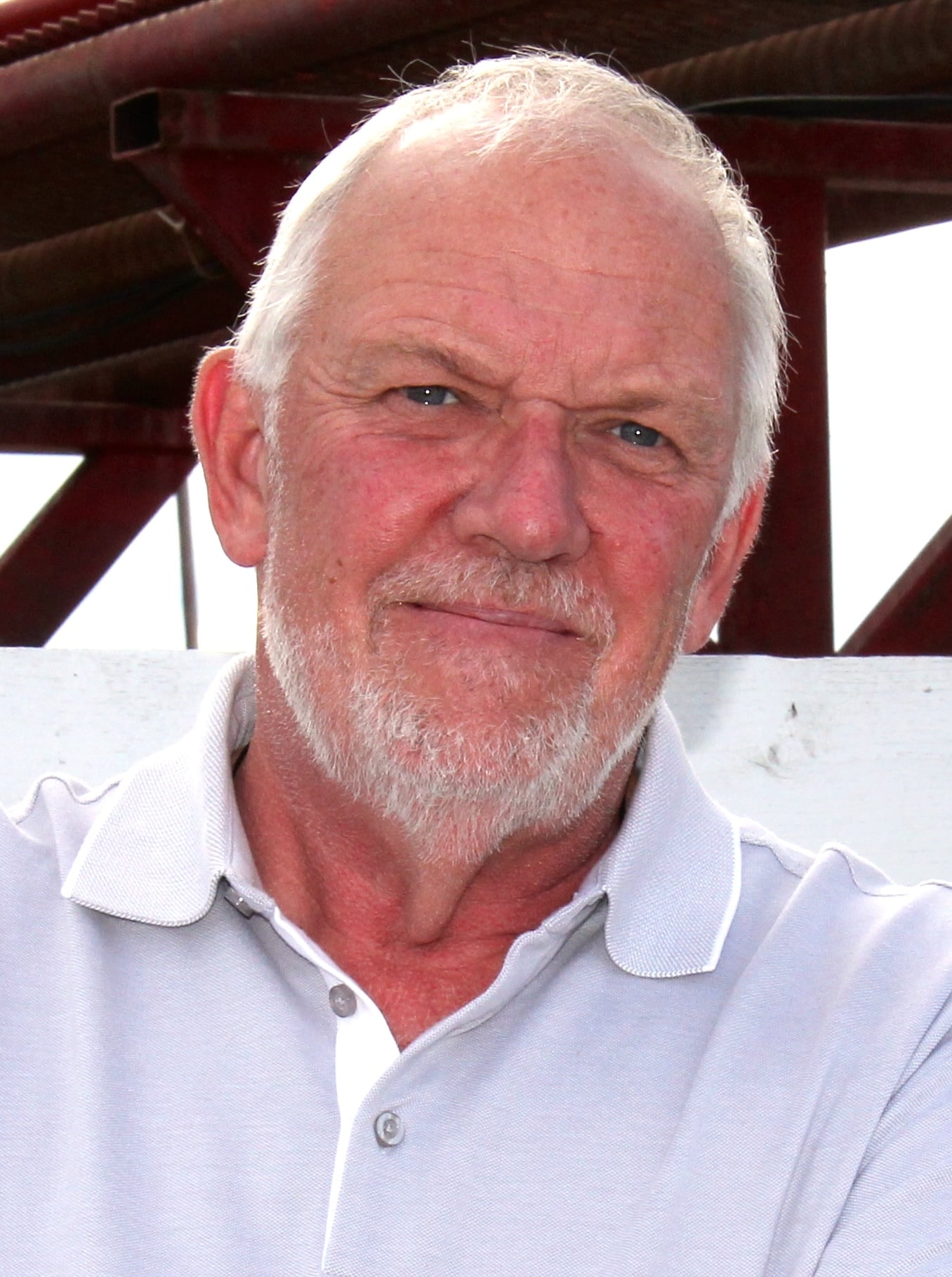

Eric Steeves says raising sheep on forages grown under thousands of acres of solar panels provided economic stability and perhaps even saved his family’s fifth-generation southern Alberta grain farm.

It certainly wasn’t an overnight process, and it involved a steep learning curve, but Steeves says being involved in Canada’s largest renewable energy, solar power generation project has been a game changer not only for his family’s Yetwood Farms, but for several other family farms in the Lomond area, about an hour north of Lethbridge.

The system of grazing sheep (or really any agricultural activity) under arrays of solar panels is known as agrivoltaics. For most that is not a household term. Agri of course relates to agriculture and voltaic (pronounced vol-tay-ick) refers to some process that generates electricity. You put them together and the term refers producing an agricultural commodity under these solar fields. Agrivoltaics is a relatively new concept to Canada, but has been used with solar power generating projects in the United States and other parts of the world for many years.

Read Also

Grazing ‘sweet spot’ boosts pasture performance

Timing-focused approach to pasture management touted to boost forage growth, livestock gains while also cutting farmer labour and inputs

The Steeves family were just regular grain farmers, cropping about 6,000 mostly dryland acres of grains and oilseeds when they were approached in 2017 by Calgary based Greengate Power Corporation asking if they would make land available for a solar power project.

“I thought the first phone call was a joke,” says Steeves. “Some sort of scam as they were talking about a large solar project. There was a second call and I said if this is legitimate why don’t you come here and have a meeting with the people to properly explain the project.” So they did. Starting in July 2017, the company met with several farm families in Lomond during a number of meetings, which resulted in contracts being signed in October 2017.

That was the beginning of the Travers Solar Project “a trail blazer among solar power projects in Canada,” says Steeves. The project itself, today the largest solar project in Canada, involved installation of 1.3 million solar panels in arrays covering about 3,400 acres of farmland. The Steeves family has about nine quarters or 1,440 acres being leased to the project, while several nearby farm families leased another 14 quarters or 2,240 acres to Greengate.

It took about two years for the company to obtain all necessary permits. Construction started in 2020 and the project was completed and producing power by late 2022. The $700 million project is designed to generate 465 megawatts of electricity which in general terms is enough to power more than 150,000 homes.

So how did the Travers Solar Project benefit Yetwood Farms and the other producers who leased their land to the project? First of all are the lease payments from the energy company. Depending on the project, lease rates can range from $700 to $1,200 per acre per year. On top of that if the landowners are contracted to look after vegetation control — keep the grass and weeds cut under the panels — that can be worth another $200 to $400 per acre per year.

“When we looked at the project, here we are farming in the Palliser Triangle — the brown and dark brown soil zone — and on average our net return from crop production would be around $70 per acre,” says Steeves. “That’s an average. Some years better and during several years of drought conditions we could collect crop insurance which was less. Whereas on those acres leased to the solar project a person can potentially earn from $900 to $1,600 per acre just to have the project there. We saw getting involved with the solar project as an excellent opportunity to diversify the farm. With mostly dryland crop production and years of drought, this project has perhaps saved our farming operation, along with other family farms in the area.”

But, don’t these solar projects take good farmland out of production? Not at all. That’s were agrivoltaics kick into gear. When these large solar projects were first introduced in Alberta, for example, the asset owners wanted the bare ground underneath the solar arrays covered with forages. But it was soon realized that the real risk to these solar panel arrays wasn’t hail, although that can be concern, but potential for grass fires that could wipe out the whole operation. Hence the need for vegetation control.

There could be mechanical means for removing the forages, but with spacing of 21 feet between solar arrays and only about four feet of clearance under the panels when they are in the table top position, mowing and perhaps even baling the forage for removal would require specialized equipment.

For vegetation control in other solar projects around the world, grazing livestock — namely sheep — under and around these solar panels was a common practice.

“My dad had raised pigs at one time and we did run some cows at different times years ago, but I had zero experience with sheep,” says Steeves.

In preparation for the providing vegetation control for the solar project under construction, Steeves bought 50 sheep in 2020. He wanted to get some idea of what it was like to manage sheep.

“I soon realized that sheep are a lot different than cattle and for a project this size I was going to need some expert help with management,” he says. Steeves did some research, located an expert on sheep, a professor specializing in small ruminant livestock, who was managing a ranch raising sheep and goats connected with the University of Mexico, in Mexico City. He was interested in working on the Yetwood Farms project. In late 2023 he moved to Alberta and has been managing the flock.

Today, Yetwood Farms, which is managing the sheep and vegetation control for the entire Travers Solar Project, is running 2,000 head of breeding females. The plan is to increase that to 3,500 ewes over the next year and within five years grow the flock to about 8,000 head. They have built lambing facilities as well as feedlot for finishing lambs. The plan is to manage the flock so it is producing lambs on a year-round basis. Lambs are finished to an average of 130 pounds and marketed through the Westpine Meats processing plant at Innsifail in south central Alberta.

Steeves says when the flock is fully stocked, it has potential to produce about 13,600 lambs per year, with a total carcass weight of about 850,000 pounds of meat. If the price averages about $5 per pound that meat has a total value of $4.25 million. Along with land lease rates to farmers, agrivoltaics provides further return to producers through sale of agricultural commodities such as lamb.

Interestingly, the wool from the sheep has no value as a fibre. As sheep are shorn annually all wool, which is high in nitrogen, is mixed with manure and composted, with the compost applied to the Yetwood Farms annual crop acres. The farm hires contract shearers to shear the flock. Shearers are paid about $6 per head. A shearer with proper technique can shear up to 30 sheep per hour.

While sheep is a very common commodity for agrivoltaics, he says there are many options. There are a number of research projects across Canada, including Olds College, looking at the potential to produce poultry, hogs, beef cattle, hay and even annual crops under properly designed solar projects.

The sheep flock at Yetwood Farms is managed in an intensive rotational grazing system. The ground beneath the solar panels has been seeded to a forage blend. Right now the flock is divided, with 1,000 head of sheep grazing on about 60 acres and moved weekly. As numbers increase there will be multiple flocks moving through the field of solar panels. With rotational, mob grazing, they are able to run two to two and a half sheep per acre for the grazing season. With more extensive grazing management in the early days, carrying capacity was in the 0.8 to one sheep per acre range.

Steeves says the farm did invest in a low-profile Avant 860i loader which can travel between the arrays. It can be outfitted with a boomless sprayer to apply herbicide. For seeding they also have a small custom built air seeder that works between the solar arrays.

“If we have bare ground the air seeder is probably the best way to get grass established,” says Steeves. “But in areas were we want to renew or add forage species we found the best approach is to hire a drone applicator, apply the seed by air, then turn the sheep on to that area to graze. The hoof action of the sheep works the seed into the soil.”

Shade from the solar panels provides the sheep shelter from the sun and also creates a micro-climatic zone under the arrays, that suits forage production.

As they tried to establish forages during dry years in some areas the kochia took over before the grass. Some areas of the pasture areas were at one time 85 per cent kochia and 15 per cent grass. But through grazing management and seeding where necessary those percentages have been reversed. “We do have a couple areas of foxtail that we will address with herbicide, but for the most part forage production is trending in the right direction,” he says.

Steeves says the agrivoltaics project has been an intense learning experience. “When we started nine years ago, it really was the wild, wild west,” he says. “There were no guidelines, or regulations. We had to learn this system from scratch and we are still learning. There were a number of pain points as we went along, but the fact is that the benefits far outweigh any pain we experienced. It is a diversification opportunity that could benefit many farms.”