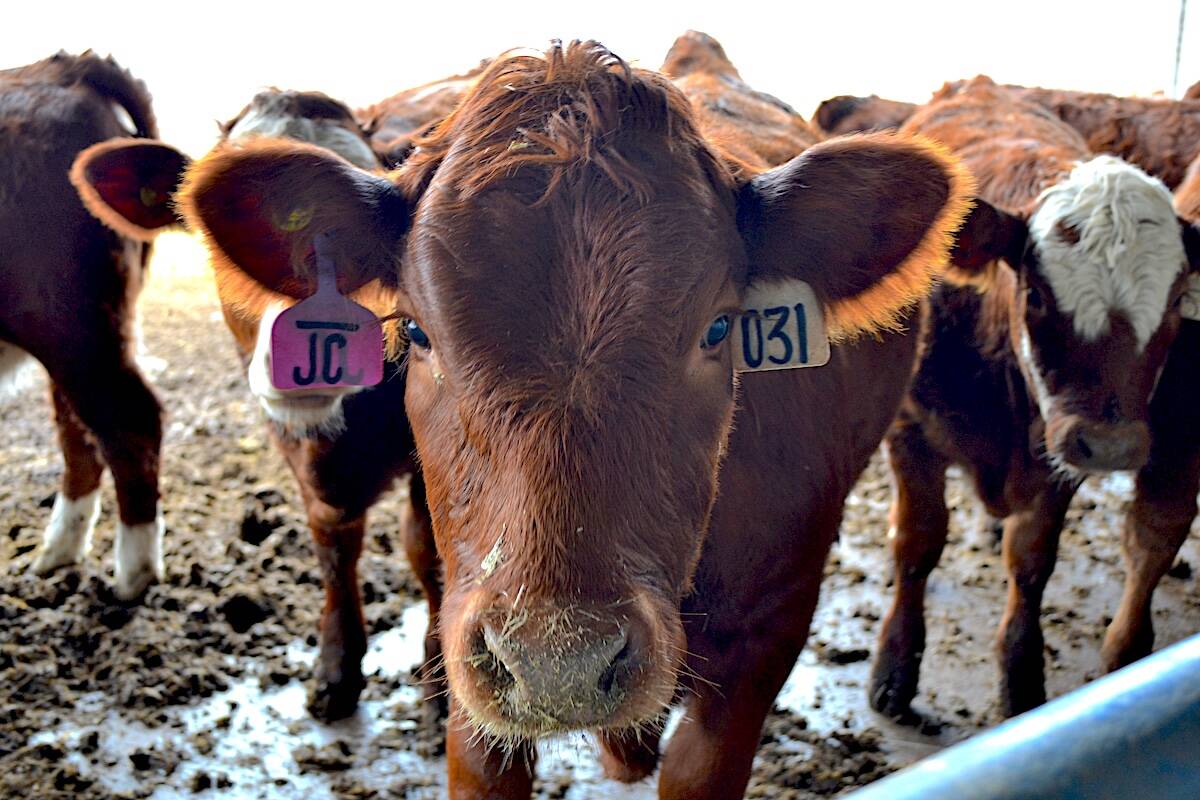

Biosecurity is a big issue in the cattle industry, yet producers continue to put it lower down their list of priorities, says Dr. Alycia Webster of Telus Agriculture.

In a presentation at the MNP Ag Connections Conference in Medicine Hat last month, she cited a survey showing only 30 per cent of producers isolate new animals and 16 per cent inquire about disease history.

WHY IT MATTERS: With old and new emerging pathogens making their rounds, having a biosecurity plan in place for cattle is important to minimize disruptions in the supply chain.

Read Also

From soil to stall: the digital platform closing the data gap in methane reduction

Maxime Leduc’s ‘My Forage System’ helps livestock producers boost profitability and slash emissions by finally connecting field data to animal performance.

The Beef Cattle Research Council divides biosecurity into a three-part strategy: bio-exclusion, management and containment.

The council has developed interactive map diagrams for producers to use to list all biosecurity risks and identify major points of entry for disease on their operations.

A common entry point is people accessing the facility, but secondary points must also be identified, such as side rooms where dead stock may be transported, a dead pit or an area where many different species graze.

“Animal movement is probably the most important,” Webster said.

“If you can get your cows from moving anywhere, having everything sourced on farm, you wouldn’t have any mingling. You wouldn’t have that unknown factor of where was this animal, what has it gotten? You don’t have that missing history.”

She said producers increase their risk for diseases by 2.2 per cent if they are buying outside cattle, while another study showed an increased risk factor for calves born in a herd where older mature cows were purchased a few months before calving.

Webster advises two weeks of quarantine for new outside animals coming into the herd. If producers do not have the land space, they can perhaps divide pastures with a temporary wire fence.

“If you don’t know what you’ve got, but you have a sick animal, move it two fence lines away from the rest of the herd,” she said.

“You need to not have that nose-to-mouth contact or nose-to-tail contact with the next fence line because you’re still not isolating them. If you don’t have that distance in the airborne pathogen to separate them, you’re still going to be sharing, so you’ll do all your efforts to try and move them into that spare space you have on the farm.”

Tools and equipment should be another focus.

Webster said it’s critical to do an inventory of what is needed and updated as well as looking at doping best practices and building consistent habits to maximize their efficiencies. It can be something as simple as gloves to minimize zoonotic disease transfer between humans and animals.

“It’s not necessarily that contact area that we’re trying to prevent you from getting something from them, or you’re giving something to them,” Webster said.

“Gloves are just a reminder for you not to touch your face after if you have something on your hands that makes you think you’re not gonna pop something in your mouth.”

She said precautions will end up being ineffective if good biosecurity habits are not formed, such as forgetting to hose off boots or equipment before applying disinfectants or having the spray radius leak from the dirty to the clean zone.

“If you disinfect before you get rid of the debris, you often deactivate that disinfectant. It doesn’t work on organic material.”

She said the contact time needed for disinfectants is often 10 to 30 minutes.

Dividing a farm’s animal areas into “clean” and “dirty” zones helps build habits as well ensuring that biosecurity tools are used for their intended purpose. Simply drawing a line between the two zones is not enough because workers won’t notice it. Instead, a physical barrier is needed as a reminder.

“Like a little boot stock where you sit down, take off your old boots, leave your house shoes over here, hop over and grab some boots on the other side. Something to make you stop and think about what you’re doing.”

Because of a new emerging high pathogenicity avian influenza, dairy producers and their workers would ideally use gloves, goggles, a mask and a hair net along with other protective equipment.

The standard is not as high with cow-calf operations, but erring on the side of caution is always encouraged.

Current pathogens of concern are foot-and-mouth disease, BVD, BLV, salmonella, cryptosporidium, E. coli, coccidiosis, BRSV, IBR, PI3, trich, digital dermatitis, lice/mites, Johne’s disease and neospora caninum.

“Do you have a scouring calf isolation somewhere where you’re going to be going in and nursing a bunch of bottle cows that have scours to get them through?” Webster said.

“We need to have some of this just to protect you, to protect the next calf, and before you go back out again and find the next calf out in pasture, that that second stock can help save another calf from getting that extra dose of scours.”

There are steps producers can take to prepare for the next veterinarian visit, such as helping set up protocols to identify sick animals and training new staff to tell the difference between a depressed and lively calf.

Stay up to date on effective common herd problems and effective medications.

Assessment plan templates can be found online, including at Healthy Farms Healthy Agriculture. There are farm bio-security signs that can be printed off and posted on the farm in both English and Spanish.

Rules of thumb to intervene depends on mortality and morbidity rates.

“Morbidity is how many treatments you have if you have an outbreak. We have defined it as 10 per cent that are treated within recent timeline, not over the course of the full year,” said Webster.

“If you have one dead calf, profitability is on your mind, but you’re also going to be worried about the rest of the heard. You’re probably going to reach out to your vet and you’re probably gonna get you a diagnosis by the time you have a second or third one.”