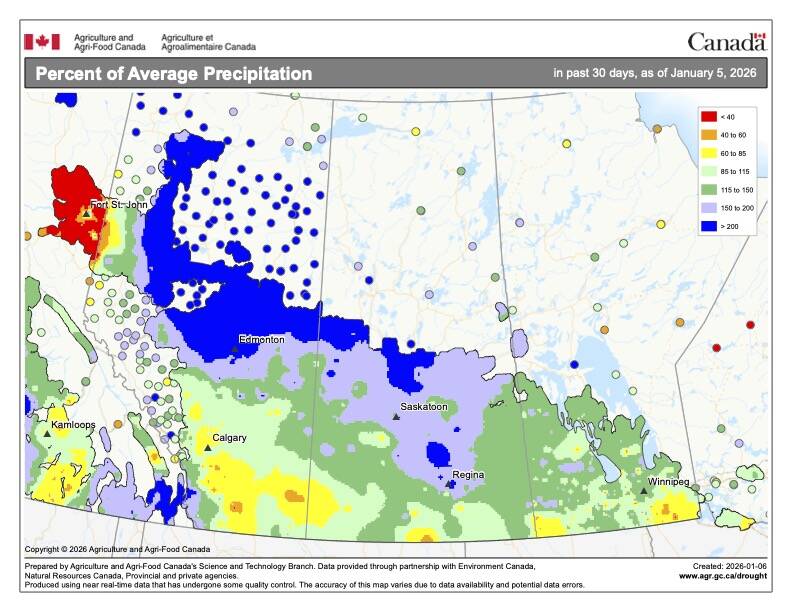

It’s been an active weather pattern over the past month or so, with numerous fast moving low pressure systems — which gives me a great excuse to take a look at this phenomenon.

Many of our most memorable fall and winter storms, whether they bring heavy snow, strong winds or a sudden drop in temperature, originate from areas of low pressure that form immediately to the east of the Rocky Mountains.

One of these development zones sits over Alberta, producing what we fondly call an “Alberta Clipper,” while another forms farther south over Colorado, responsible for the infamous “Colorado Low.”

Read Also

Taking the farmers’ market online

Two Albertans, who have a cow-calf operation near McRae, had the idea to create Arvo, an online farmers’ market, after being unable to find beef from within their own community.

So, let’s revisit why the lee of the Rockies is such a breeding ground for storm systems and why certain lows grow into major weather makers while others barely organize at all.

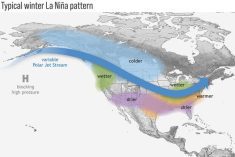

We’ve previously discussed how the jet stream, with its sweeping curves and shifting speed, helps shape regions of rising and sinking air. When the jet accelerates, rising motion and low pressure often develop beneath it. When it slows, sinking air and high pressure tend to form. While this plays a supporting role, it doesn’t fully explain why lows so often take shape immediately east of the mountains.

To understand that, meteorologists talk about vorticity, a measure of how much spin an air parcel has. There are several types — absolute, relative and the Earth’s own vorticity — but the fine details can be complicated enough to test anyone’s patience. Instead, we’ll focus on the main ideas needed to understand how lee-side lows develop.

As you move closer to the equator, the Earth’s vorticity decreases. Relative vorticity, meanwhile, refers to the air parcel’s own spin — counterclockwise rotation adds positive vorticity and clockwise rotation adds negative.

The important concept is that absolute vorticity, which combines both the Earth’s vorticity and the parcel’s relative vorticity, stays constant unless something forces it to change. So, if an air parcel moves southward and the Earth’s vorticity drops, the parcel must gain relative vorticity to maintain the balance. If it moves northward, the opposite happens. Increasing vorticity encourages cyclonic (low pressure) development, while decreasing vorticity promotes anticyclonic (high pressure) behaviour.

Upward bound

Now imagine Pacific air flowing eastward toward the Rockies. When it reaches the mountains, it is forced upward. At the same time, the tropopause acts like a rigid ceiling, preventing the air from expanding upward as much as it would like. The result is that the atmospheric column becomes squeezed vertically and must, in turn, spread out horizontally. When the column becomes shallower, its absolute vorticity decreases. Because the Earth’s vorticity hasn’t changed at that moment, the parcel’s relative vorticity also has to decrease. This gives the air an anticyclonic, or southeastward, turn as it flows over the mountains and spills down their eastern slopes.

Once the air begins drifting southeast of the Rockies, however, it is now entering a region of lower Earth vorticity. To compensate, its relative vorticity must increase. This creates a cyclonic bend in the flow, turning the air northeastward. Put together, these shifts form a trough of low pressure stretching along the lee of the mountains — a crucial first step in the development of an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low.

The next question is why some of these troughs intensify dramatically while others fade. The Rockies themselves play a major part. These are among the tallest mountains on the continent, and their height forces a dramatic squeeze on the air column. The stronger the squeeze, the more the vorticity must adjust, and the deeper the resulting trough. But a trough alone is not enough to guarantee a storm. If it were, we would be dealing with a constant conveyor belt of major lows sweeping across the Prairies all winter long.

Other factors at play

To develop into a significant system, several additional ingredients must align. Cold Arctic air often slides southward along the mountains, while warmer, moister air waits to the south. When the developing low taps into both air masses, a strong temperature gradient forms which is a key source of energy for strengthening storms. The moisture adds even more fuel as it rises and condenses, releasing heat that intensifies the system. When these ingredients line up perfectly, an Alberta Clipper can quickly spin up and race eastward, bringing snow, wind, and rapid temperature changes.

Colorado Lows, meanwhile, owe much of their punch to their southern position. Like Clippers, they draw cold air from the north, but they also have access to warm, moisture-rich air from the Gulf of Mexico. Because the Gulf is one of the most reliable moisture sources for the continent, these systems sometimes tap into deep, sustained humidity. As this warm moist air rises and condenses, it releases a tremendous amount of heat, fueling rapid development. This is why Colorado Lows can grow into sprawling, slow-moving storms capable of affecting vast regions at once.

Still, not every setup produces a major event. A storm might have abundant moisture but lack Arctic air, limiting snowfall and reducing the system’s strength. A promising low might start strengthening only after it has moved east of us, missing the Prairies entirely. Other times, a lack of cold air shifts the storm track farther west, producing more rain than snow or allowing the system to slide too far south to have much impact.

With so many moving parts like the jet stream position, mountain effects, temperature contrasts, moisture supply and timing, it’s no surprise that forecasting these systems can be challenging.

Whether all the ingredients will come together for a major storm this winter remains an open question, but one thing is certain: the unique geography of the Rockies will continue shaping our storm season, just as it has for generations.