A holistic approach to livestock grazing is not a new one, the founder of agriculture’s holistic management movement recently told the Holistic Management Conference in Taber, Alta.

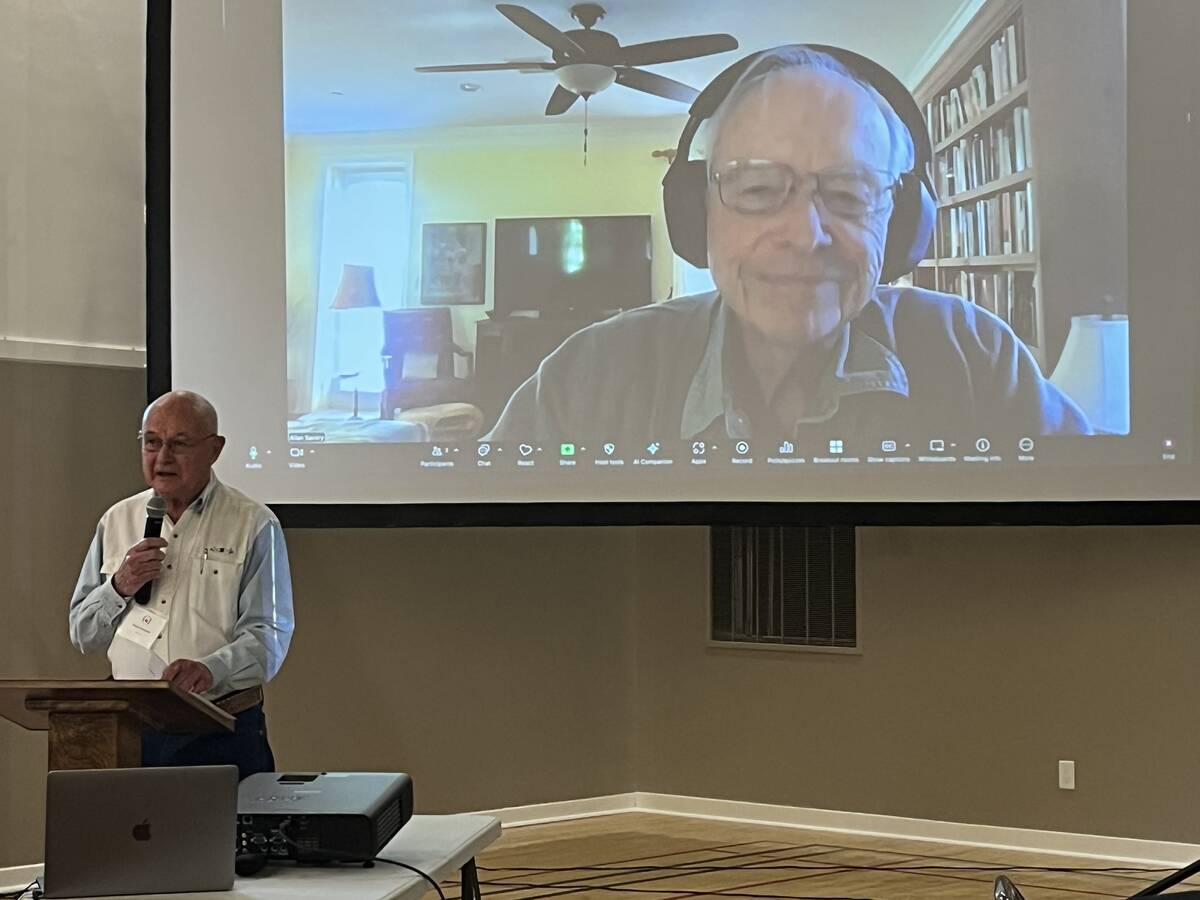

“We would be very arrogant if we said we were the first to take a holistic approach and see our connection to our life-supporting environment,” 90-year-old Allan Savory, who splits his time between Zimbabwe and his home in Florida, said during a virtual question-and-answer session.

“As far as I know, every single Indigenous culture in every part of the world saw that. So that’s been seen for 50,000 years by humans. It was only lost in modern Western science the last two or three centuries. The common example that’s given is Native American tribes seeing the damage to the environment. They didn’t have laws, they didn’t have regulations, but they had to do some customs.”

Read Also

Alberta producers share why on-farm research drives success at RDAR showcase

Farmers explain how producer-led trials and strategic data collection are bridging the gap between the lab and the field in their operations.

WHY IT MATTERS: Taking a different approach from traditional agricultural practices can help move the world to better land management.

The holistic principle for grazing livestock builds on the concept of rotational grazing.

Cattle can rehabilitate degraded land by mimicking the natural grazing patterns of wild herds of herbivores as they escaped predators while packed in large herds and frequently moving between different areas.

High animal impact over shorter grazing periods gives the land time to make a full recovery before being grazed again.

The animals are used to to break soil crust, trampling older material to build cover and using manure and urine as fertilizer.

Creating conditions that favour perennial grasses and forbs, if done correctly, can produce denser, deeper-rooted grasses, better biodiversity and water infiltration to go with higher carry capacity over time.

The triple bottom line

Savory has seen it all: farming and ranching, consulting in five countries and working as an ecologist, wildlife game officer, public servant, solider and member of Parliament.

Many livestock producers at the conference swear by the principles drafted by Savory as he formed the foundation for the Savory Institute in the United States.

He noticed that areas where animals had been excluded were degrading worse than areas that had been grazed and then allowed to rest.

It led to a significant breakthrough in understanding what was causing the degradation and desertification of the world’s grasslands and planted seeds of holistic management.

A holistic approach combines the principles of life and family (time, stress, purpose, succession), economics (profitability, cash flow, debt, investment choices) and land and animals (biodiversity, soil, water cycle, animal health).

The link between finance and stewardship

Savory stresses that producers cannot just “manage the land” while ignoring other tenants. A short-term, ultra-aggressive profit motive can destroy soil health, but a “green” practice that improves the ecology but bankrupts the movement has no staying power.

“If you can’t finance your family, everything else doesn’t matter. Men commit suicide when they can’t support their families. So you manage a family, then you manage the economy. Only then do you manage nature, your farm, the ocean, whatever you’re managing there to produce every single form of food and everything that makes civilization possible,” he said.

“You can’t divide these, they have to be managed simultaneously and indivisibly. There is no chance of anywhere in the world, the same family, the same family values, the same culture, the same economy they’re operating in, or the same climate piece of land being replicated. That’s why holistic management is so unique to every single farm and family.”

Grassroots growth amidst global challenges

In a paper by Deb Stinner at Ohio State University, she talked to ranchers and farmers who trained under Savory. All but one saw an increase in biodiversity in the first year, while the average of all of those farms was a 300 per cent increase in profit. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of people in farm families went broke in the same markets.

Nevertheless, the world has been slow to implement holistic management, despite the formation of organizations such as those in Canada.

Savory applauded the efforts of the producers in the room who have adapted the holistic principles to their operations, adding it will be the producers themselves who lead the movement from the grassroots into a global consciousness rather than top-down action by government.

In the 1980s, Savory was set to help train 18,000 people in the U.S. forest service with his holistic management foundations, but the initiative was cancelled.

“What we’ve seen is since then, global biodiversity loss get far worse, desertification, as a consequence of it, get far worse. Accelerating climate change get far worse. All of those feeding on each other now in a feedback loop going out of control,” said Savory, who just published a memoir, Unsavory: African Stories of Wildlife, War, and the Birth of Holistic Management.