If your dairy cows are feeling blue, then you need to be concerned.

That was the message delivered to attendees at the recent Western Canadian Dairy conference by Marina Von Keyserlingk, a University of British Columbia professor who is recognized internationally for her research on care and housing of dairy cows and calves.

Von Keyserlingk urged producers to take special notice of transition cows, which are those that have moved from pregnancy to birth and then post-partum. The transition period covers the three weeks before birth and the three weeks after.

Read Also

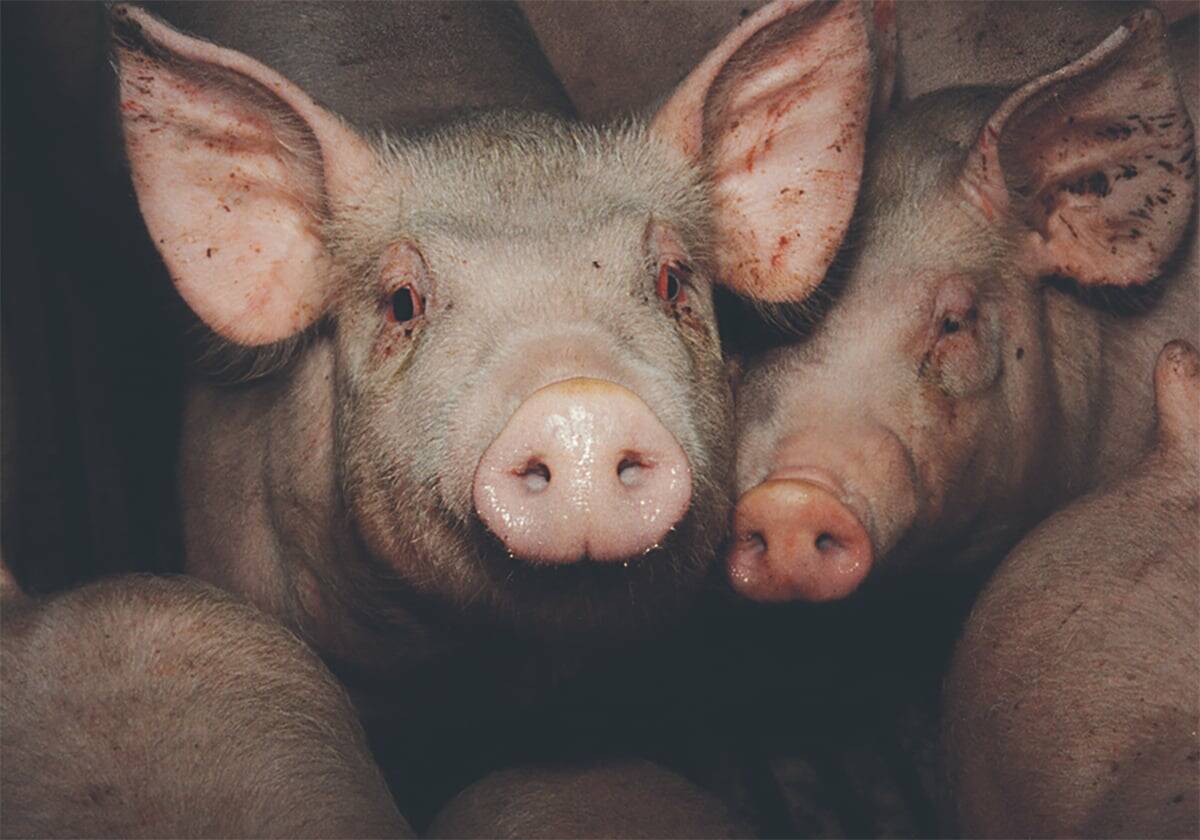

Scientists discover cause of pig ear necrosis

After years of research, a University of Saskatchewan research team has discovered new information about pig ear necrosis and how to control it.

Transition cows are important for a producer’s herd and pocketbook, said Von Keyserlingk.

“She’s your bread and butter,” said Von Keyserlingk. “When she calves, she becomes part of your lactating herd, and when she’s sick, she can’t perform at the level that you need her to perform.”

Producers need to understand they are not only managing herds but managing diseases as well, she said, because sick cattle mean reduced milk production, decreased longevity, more involuntary culls, and a hit to the bottom line.

One study of transition cows tracked cows that developed metritis, an inflammation of the uterus that causes discoloured, diseased vaginal discharges. The study monitored behaviour of a group of cows 21 days before calving, and 21 days after. Cows diagnosed with metritis by day 9 or day 12 after calving spent less time eating.

“I don’t think that anyone was surprised that sick cows spend less time eating,” said Von Keyserlingk. “What is surprising is that even a week to two weeks before they calved, we saw a reduction of time spent in the feed bunk.”

Another experiment monitored how many times individual cows went to the feed bunk and how much they ate. Over 101 cows were followed during a 10-month period. The study found healthy cows did not reduce their dry matter intake until the day before calving, recovered after a couple days, and then resumed normal eating patterns. Cows with either mild or severe metritis drastically reduced dry matter intake the week before they calved.

Video monitoring

By monitoring the cattle on video, the researcher found healthy cows spent a lot of time with their heads in their feed bunk, not even eating. Sick cows did not exhibit this behaviour.

“The video told us two things: Healthy cows were spending a good portion of their day defending their resource. They felt good,” said Von Keyserlingk.

Dominant, healthy cows would chase sickly cows away from the feed. Von Keyserlingk and her researchers could not determine if the cows that became sick were actually subordinate, or if they acted subordinate because they were feeling ill. However, they were able to determine that insufficient bunk space in the pre-partum phase was a huge risk factor for disease.

Lameness is also a condition that affects transition cows. Claw horn lesions show up on cows at about 12 to 15 weeks post-partum, which means they developed during the transition period. One study monitored the standing behaviour of cattle up to 15 weeks post-calving. Healthy cows stood about 700 minutes a day, with a slight increase in the weeks following calving. Cows that were eventually diagnosed with lesions on their feet spent an extra 120 minutes standing in the week to two weeks up to their calving period. Cows that developed sole ulcers spent significant time perching in their stall, with two feet up on one level and the other two in the alley.

Producers may want to try to cut down on regroupings in transition cows to reduce stress. Cows moved into a new area showed more stress than those allowed to stay in their own pen, with new cows introduced. Overstocking in the prepartum pen can be a problem for the transition cow, since she may not be able to eat enough.

“As soon as you start to overstock, they all want to get to fresh feed and if there’s not enough room, you’ve got aggression,” Von Keyserlingk said.

Overstocking can also increase standing time as cows will stand more, waiting for their turn to feed.