Alternatives Researchers call for greater crop rotational diversity and more focus on integrated pest management

Back in the days when being a farm kid spelled work and a penny was still worth five Mojos at the local store, Grandpa had us all out there one hot, July afternoon hand roguing his seed oats for a penny a plant.

If some agronomists are correct, it’s looking like farm kids of the future won’t be deprived of that developmental/family bonding/entrepreneurial experience.

Hand weeding — as well as every other means of offing herbicide-resistant weeds before they go to seed — is now being promoted as a measure farmers should consider if they want to avoid the aggressive invasion overtaking fields south of the border.

Read Also

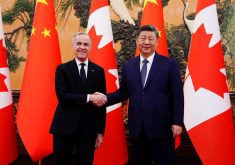

Deep cuts to ag research jeopardize Canada’s farming future

The huge cuts to ag research at Agriculture Canada are being widely panned by farm organizations, but there seems to be little hope of the government reversing its decision.

Just a couple of years ago, we brought you stories of Arkansas cotton farmers whose farm trucks, once loaded with herbicide containers, are now filled with hoes. Well last fall, provincial agronomists in Manitoba visited fields just across the line that are infested with weeds resistant to at least one, if not multiple herbicides.

Some weed scientists are openly questioning the agronomy industry’s single focus on herbicides, particularly the introduction of stacked traits — varieties that are tolerant to multiple active ingredients.

“Why are so many weed scientists and extension personnel recommending more herbicides to mitigate herbicide-resistance problems?” asks an editorial by six leading Canadian weed researchers, Neil Harker, John O’Donovan, Robert Blackshaw, Hugh Beckie, C. Mallory Smith and Bruce Maxwell published last year in the journal Weed Science.

These researchers argue promoting “herbicide diversity” and stacked-trait technology as the solution to herbicide-resistant weeds is short sighted at best. “Multiple resistance to herbicides with different sites of actions has occurred in the past and will increasingly occur in the future,” they say.

They call for greater crop rotational diversity, more focus on integrated pest management and fewer in-crop applications of glyphosate.

“Are we a discipline so committed to maintaining the profits for the agrochemical industry that we cannot offer up realistic long-term solutions to this pressing problem?”

In a 2011 essay, Robert Zimdahl, a retired weed scientist from Colorado State University, eloquently describes the root of the problem.

“Most biologists accede to the view that their research is contributing to an expanding view of nature that will never be complete. However, in some sectors of biology, and I think especially in weed control, scientists may not operate from this broader biological perspective. We know weed control is evolving, but its evolution has been constrained because 20 years ago the science focused almost exclusively on a single solution to the problem. The desirable goal of weed control was too frequently hitched to the technological achievement of herbicides.”

Farmers can’t control the weather. They can’t control the markets. But on this one, they are in the driver’s seat. They are the ones deciding what to grow. Maybe the idea of hand weeding your fields has appeal. For the record, those memories are fond ones.

The problem is, pennies are being phased out, the fields are bigger and there aren’t that many farm kids around anymore.