Many conventional agricultural practices generate a homogenous soil habitat — and that’s not a good thing, says soil ecologist Jeff Battigelli.

“Basically, you just keep knocking things down. It’s not allowed to get very complex; there is a simplified community structure, with very few species,” said Battigelli.

Homogenous soils need constant human intervention and resources to keep them functioning.

“We’re having to till the soil, apply fertilizer, pesticides and fungicides and that sort of thing to keep the productivity up,” he said.

Read Also

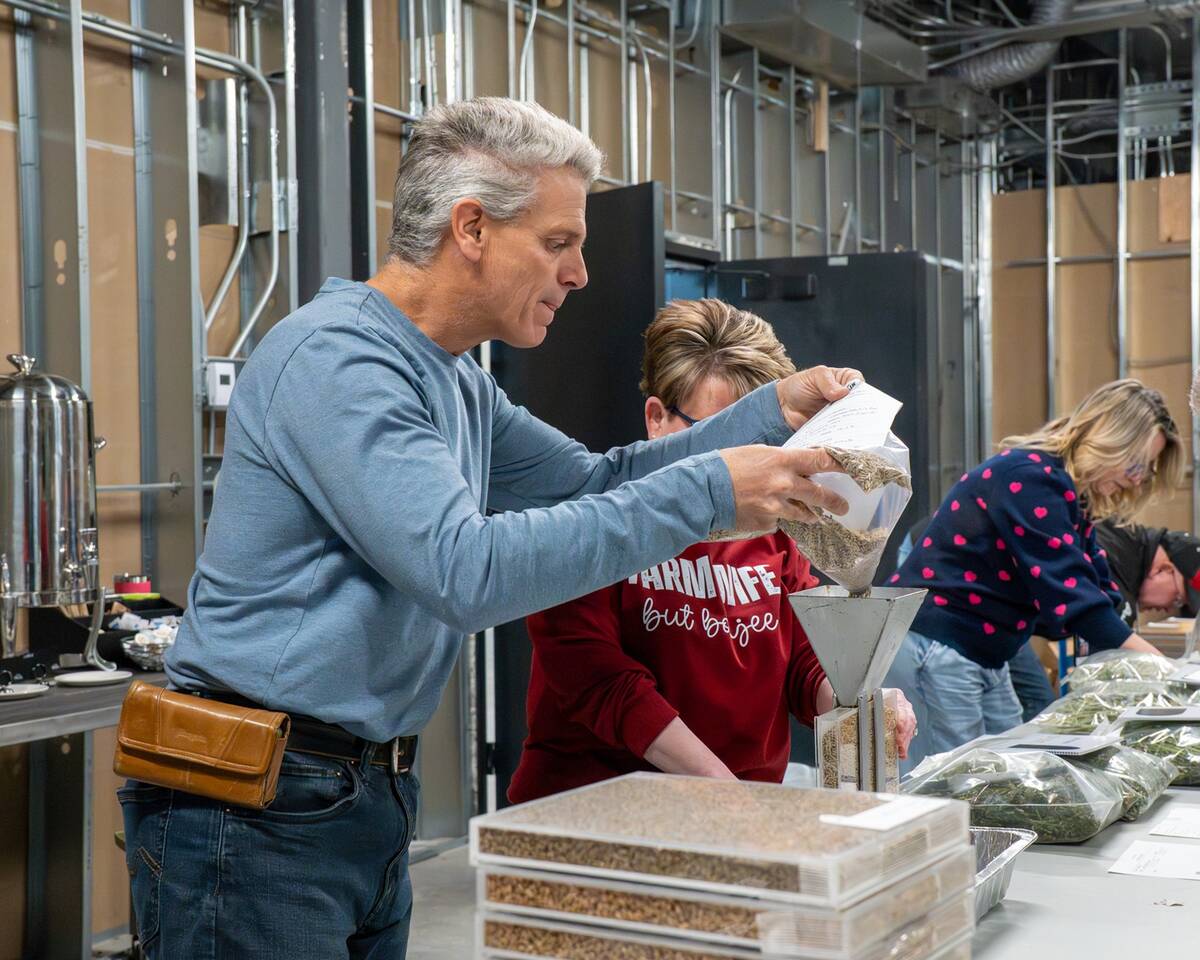

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

For example, bacteria tend to be the dominant organisms in tilled fields, and that means the decomposition rate of organic matter is increased and there is fast nutrient mineralization.

“You don’t have a lot of those nutrients hanging around to get utilized by the plants when they need that material. You constantly have to add fertilizers to the soil so plants have those nutrients and minerals to take up.”

Zero or minimal till slows down the decomposition rate; increases density and diversity of soil biota; and allows for more fungal growth, which keeps more nutrients in the soil profile.

“Potentially, we’re using fewer resources to keep that system functioning,” said Battigelli.

Fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides cause direct and indirect effects on soil organisms.

Lethal doses can kill the organism outright, or change the chemical environment so the organism dies. Chemicals can also impact the microclimate, causing organisms to leave or die out. Nitrogen fertilizers change the soil pH and organic matter content. They also influence the food supply by affecting the bacteria and fungi and reducing certain types of worm populations. Higher doses of nitrogen fertilizer can decrease mesofauna populations while urea increases bacterial nematode populations, which influences decomposition rates. Ammonia applications decrease bacterial feeding in nematode populations.

But you can’t make blanket statements as pesticides and herbicides have different effects on different organisms at a species and genus level.

Sometimes there is a positive impact, sometimes a negative impact, and sometimes no effect. But chemicals do change populations.

“It really does depend, when we are applying these chemicals, what organisms are present on these sites and how they are going to respond,” said Battigelli.

Ideally, producers should try to use biological control to limit pathogens and pests. By increasing biodiversity and having a healthier soil ecosystem, the need to apply pesticides or fungicides is reduced because pests are already being controlled by organisms in that system. A healthy biodiversity in the soil also aids nutrient decomposition and nutrient cycling, reducing the number of chemicals that need to be applied long term.

Grazing can also have negative consequences if not done properly.

Just by walking around, livestock cause a loss in air and pore spaces that are critical for organisms to move around in. They also alter soil temperature by removing organic matter and litter, and affect nitrogen levels, moisture content, and the aggregate stability of the soil profile. Grazing can reduce soil organism diversity and density and cause bacteria to dominate the system.

The only way to combat this is to reduce the concentration of grazing and have fewer animals grazing for a shorter amount of time, said Battigelli.

“Don’t rock the boat too much and allow these organisms to perform the routines, services and duties that they do, and help out where we need to help out,” he said.