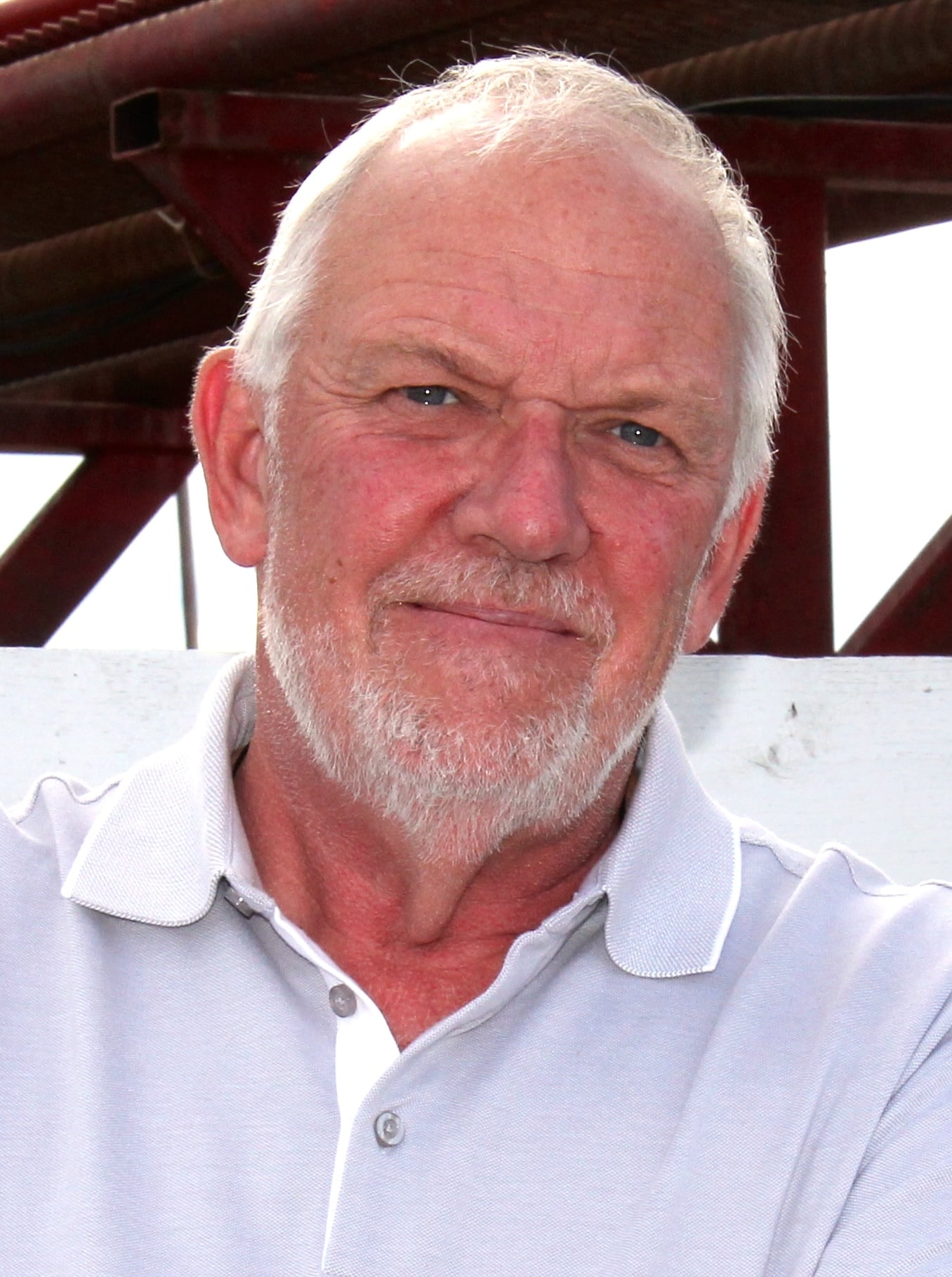

Fortunately in my career I have always been at the forefront of technology. That doesn’t mean I use it or understand it, but I like to think I’m out there ahead of the pack looking frustrated and confused.

The fact that in 2025 I can somewhat navigate a few functions on a smartphone in itself is quite amazing. When I started school — I jumped right into higher learning i.e. Grade 1, there was no kindergarten — we learned to write with pencils, and across the rows of desk of that one-room schoolhouse I was deeply envious of the big kids — Grade 5 and up — using ink pens. No ball point pens yet; these were the often messy, but no-fail straight pens with nibs you dipped in an inkwell. I dreamed of someday having my own nib pen, inkwell and blotter.

And eventually I got there. However, the required use of a straight pen in my early learning was short-lived, as Ontario finally allowed the use of the new-fangled ball point pens in 1958. It was those early days, however, that began my fascination with pens which still haunts me today.

Read Also

From MasterChef to ‘Barndominium’: Rootstock Ranch fires up the grill

Marianne Smeaton, from Charlie Lake, B.C., is opening an event centre with a menu featuring her homegrown Wagyu beef after appearing on MasterChef Canada’s finale.

On my desk at any given time I have three containers that hold a wide selection of ball point and gel pens, and I usually keep half a dozen favoured pens handy within easy reach beside my note pad. I also still carry and quite often use a couple of fountain pens, and on special occasions, I will drag out a bottle of ink and nib pens when planning to write a message with impact. (I want them to know this message is so important I resorted to using a 200-year old writing instrument.)

Back to my point on technology. About 35 years ago in the early 1990s, I recall talking to early-adopter farmers who were beginning to use yield monitors in their combines. I forget the details of the complications, but while these early monitors were collecting data, producers had to consult technical specialists to understand what that data meant. And I believe the general advice was that farmers would need to collect several years of data before it was of much value. A lot of data, and people weren’t sure what to do with it.

Then a few years later, John Deere was one of the first on the market in the mid-1990s with tractors equipped with GPS guidance systems. Farmers could ride the tractor all day and not have to pay attention — it steered itself. This certainly sounded like a holiday for field workers.

Now we jump forward a few more decades and the world is learning to understand, manage and adopt AI. Is everyone ready? I don’t think we have a choice. I haven’t done a lot with artificial intelligence myself, although my wife would argue that some days I haven’t done much with natural intelligence either. We’ll just ignore her.

But AI is already very much a part of everyday living. If I use Siri or Alexa on my smartphone to find music or answer a text message, that’s AI. If I’m on hold with the bank or some other service and I receive the option to “chat” through text messages with Robert of Melissa (or whatever name), that’s all AI-generated information, which usually doesn’t address my specific need, but they try.

AI involves collecting and analyzing huge amounts of data on any particular procedure, activity or topic, which is then used to develop algorithms. And an algorithm is essentially a set of step-by-step instructions for solving a problem or completing a task.

The algorithms can be used in programming a computer telling it exactly what to do and how to get the final result. Computers use algorithms to help them make decisions, process data or perform actions automatically. They can be very simple, like sorting a list of numbers, or very complex like operating robotics, autonomous vehicles and drones.

For farmers and the agriculture industry, AI has become intrinsic and mostly helpful in transforming daily activities through tools such as precision farming and automated machinery. It wasn’t long ago I was talking to a young dairy farmer from New Brunswick, who had installed robotic milkers. It didn’t necessarily reduce the workload, but it freed up his time from one chore to concentrate on something else that couldn’t be automated. Ultimately, the goal is to provide information and guidance to improve efficiency, sustainability and all kinds of yields for both crops and livestock production.

There are newer high-end terms such as data-driven decisions and predictive analytics. In my simple world I might say nine out of 10 times this or that is likely to happen, whereas AI collects enormous amounts of data on a particular thing to say 900 billion times out of a trillion this is likely what will happen.

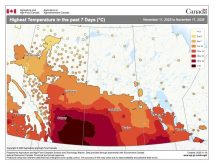

AI can analyze vast amounts of information captured by sensors, drones and satellites and provide a pretty educated guess on monitoring crop health and how to manage pests and diseases, for example.

AI becomes the brain power to direct robotic weeders and harvesters and AI-guided tractors. By analyzing a wide range of data, AI can predicts risks like weather events or pest outbreaks, helping to address labor shortages and even environmental impacts.

So there can be many potential benefits to agriculture that can lead to increased efficiency, improved productivity and improved sustainability.

On the downside, however, the new AI technology isn’t cheap. You already have a line of conventional machinery, do you scrap that and go to robotics and autonomous equipment? How do you transition? Maybe you need to keep both?

And to develop all the “brains” for this new technology, the amount of energy needed to power computers at AI data centres is staggering, not to mention a huge environmental cost.

In 2022, for example, it was estimated the power needed globally to operate AI data centres was about 460 terawatt-hours (TWh) of energy, which is roughly equivalent to the total annual electricity consumption of an entire country such as France or Japan. And energy demand from AI is projected to increase by 165 per cent by 2030. Projections suggest data centres could consume more than four per cent of global electricity by 2035.

That’s going to require more hydroelectric projects, more coal-fired power plants, more wind turbine farms, maybe even more projects collecting methane from manure, and/or more solar farms. Or this is where we look at more nuclear power plants, and the new concept of hydrogen-fueled power generation projects?

Unless it is a green energy source, generating power for these AI date centres will likely contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. And these data centres need to be cooled, which means increased water consumption. And we all know that water is usually a finite resource.

I also read there is concern surrounding AI about the long-term impact of relying too heavily on machines for essential farming tasks. However, I think that genie was out of the bottle when John Froelich built the first gasoline-powered tractor in 1892.

While technologies like electricity or the telephone took decades to achieve wide spread adoption, social media on the other hand reached global scale in about five years, and AI achieved mass adoption in just two to three years.

And let’s face it, it is big business. The market for AI exploded from $16 billion in 2017 to over $224 billion in 2024. Generative AI, a technology that barely existed in a practical form in 2021, reached a market value of nearly $44 billion by 2024, representing the fastest adoption of any technology in recorded history.

AI is obviously a train that’s not going to be stopped, and perhaps there is no need for it to be stopped. I’m no techie, but I think it is important to understand the technology as best I can and even make use of it when it provides me a convenience. Beyond that, I will let smarter, younger minds make sure AI stays within society’s moral and ethical guardrails.

I am quite content to fiddle around with my pen collection and try to get these ink stains off my hands. I believe there is even a manual typewriter in the storage room somewhere. Now there was an inspired piece of technology with only a million moving parts. Maybe I can press it back into service just in case AI implodes and my computer locks up. Much like a cultivator overgrown with weeds in the fenceline, it’s important to have a backup.