Farmers are finding the promise of marketing freedom rings hollow in the absence of enough price information to make informed decisions.

That’s prompted Keystone Agricultural Producers, Manitoba’s main farm group, to call on the federal and provincial governments to implement mandatory price reporting on agricultural commodities, similar to what exists in the U.S.

“We’ve been given the right to freedom and choice to market our grain wherever we want now… but we do not have access to all the information to make the best decisions that we want to make,” farmer Bill Campbell said in supporting the resolution approved at the organization’s recent general council meeting.

Read Also

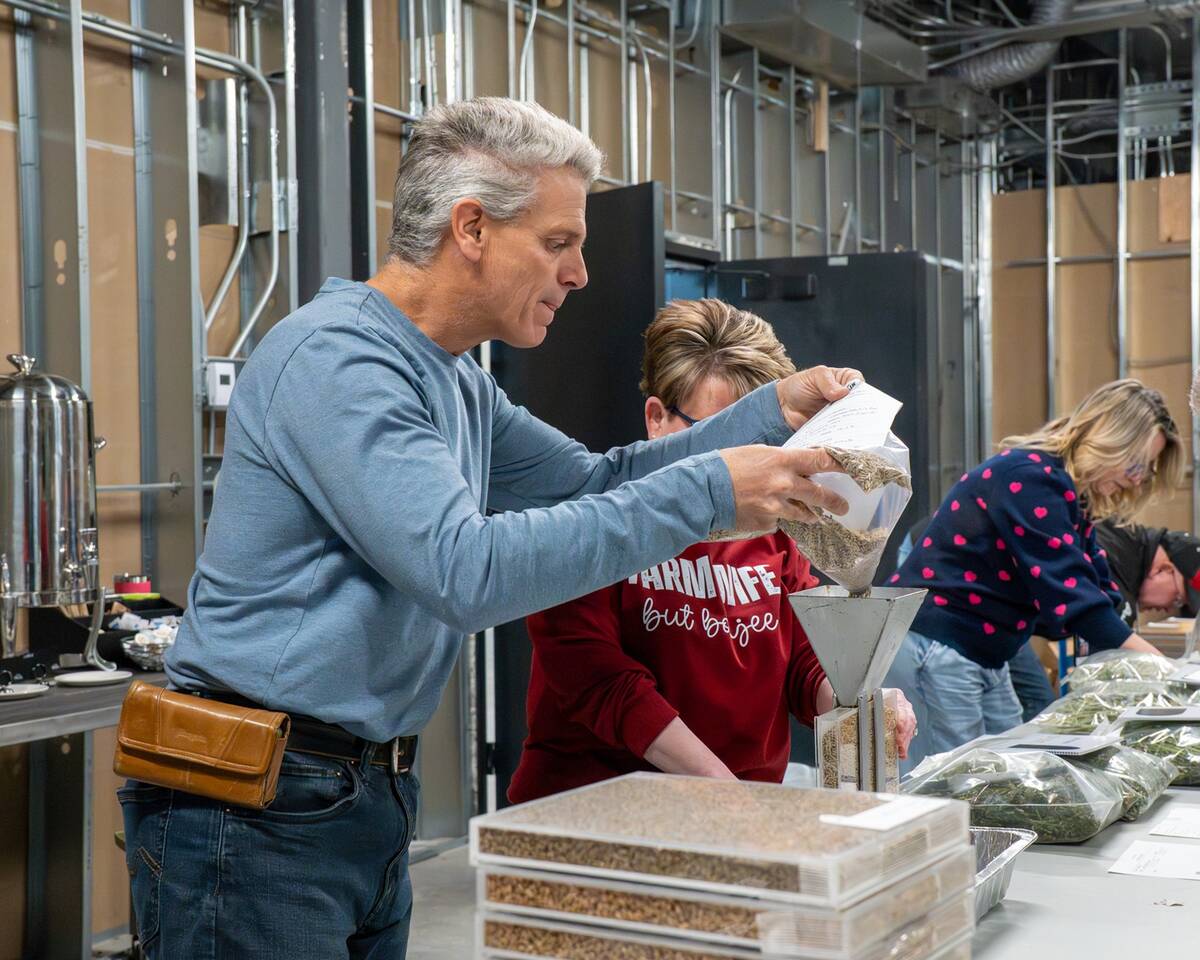

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“The companies are only going to pay exactly what you’re willing to sell for, not what they are willing to buy for.”

Farmers need a system where they can compare all grain prices before they make a delivery decision, he said.

“I think this would make the grain companies competitive, or at least more competitive.”

Grain buyers in the U.S. are compelled to report sales information to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which then makes it publicly available, said farmer Glen Franklin.

While one delegate said there’s enough price information available through future markets and from elevator companies, another said it’s not easy to get elevator prices. Some companies post prices online, while others require farmers to contact them. As well, posted prices don’t all reflect the same grade and protein content.

KAP president Doug Chorney said he agrees there’s a need for better price information. There’s often a big difference in prices between buyers, he said.

“Given the opportunity it seems some grain companies take advantage of farmers,” Chorney said.

Making grain prices at port public would help, too, added Chorney. Farmers could compare what’s essentially the world price with what they are receiving in the country and then determine if it’s fair.

One option would be to switch the delivery point for grain futures markets from places such as Minneapolis and Chicago to Canada’s West Coast, says University of Saskatchewan agricultural economist Richard Gray.

He said there are still wide differences between port prices for top milling wheat at Portland, Oregon compared to elevators in Saskatchewan. Gray blames much of the discrepancy on constrained rail and export capacity in Western Canada and on Canada’s West Coast.