Pollinators and beekeepers on the Prairies have a new champion — the first-ever research chair concentrating on the health of these essential workers in fields and pastures.

“I’ll be focused on improving honeybee health to improve sustainable agriculture,” said Dr. Sarah Wood, an associate professor of veterinary pathology at the University of Saskatchewan’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine.

“We know that honeybees are really important for Canadian agriculture. They’re contributing $5.5 billion worth of pollination services every year. If we keep our honeybees healthy, in turn, that will keep our crops healthy and productive.”

Read Also

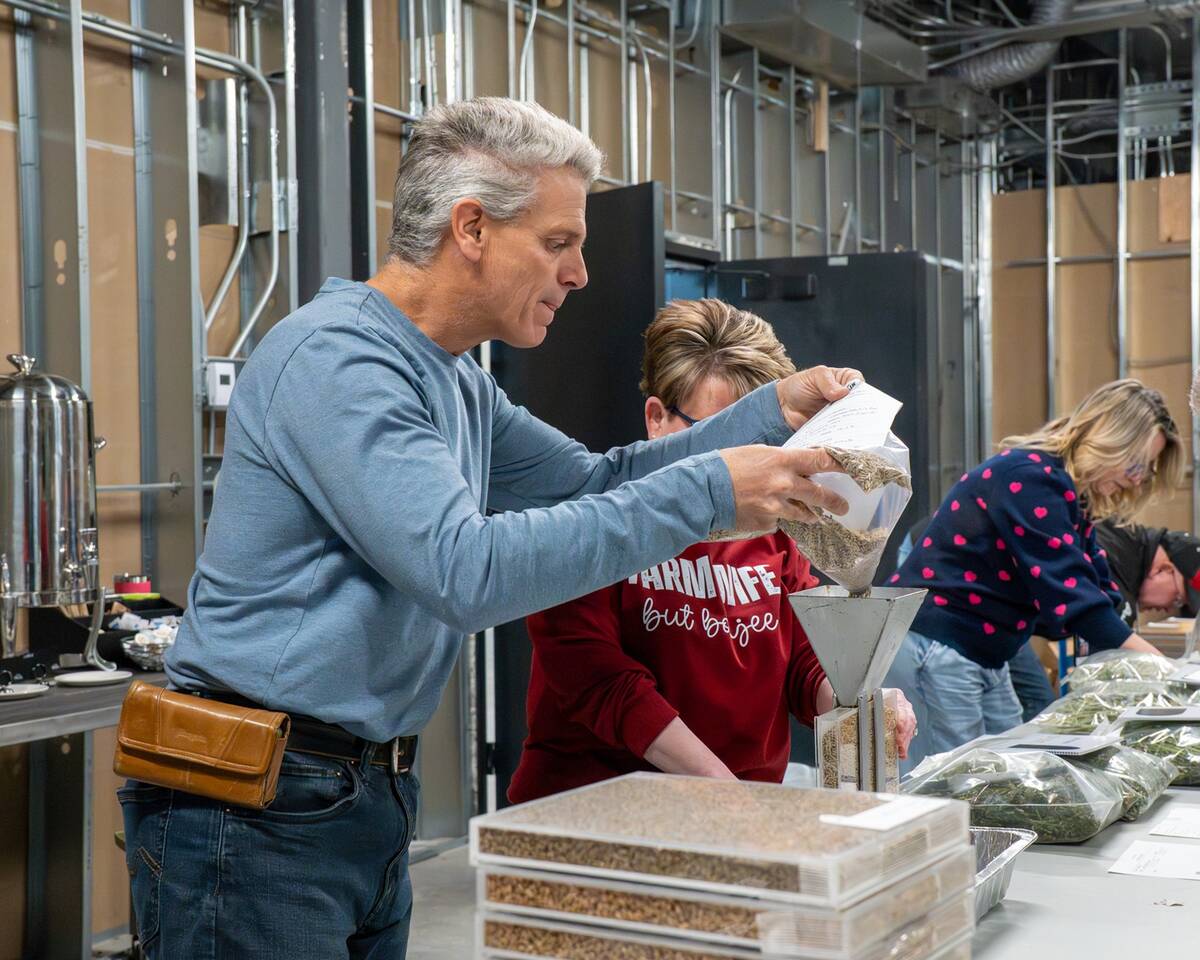

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

Wood was a veterinarian in a companion animal practice in Red Deer before turning to honeybee health and she did her PhD on one of the most contentious issues in crop production today: honeybee exposure to neonicotinoids.

The issue of neonics — a widely used group of insecticides that includes clothianidin and imidacloprid — has been controversial in both Canada and abroad. The European Commission has restricted their use, a move that has been blamed for a decline in yields and acreage of rapeseed.

There were fears of similar restrictions here but, while Health Canada has limited their use in horticulture, it concluded that neonic seed treatments for canola did not pose a threat to pollinators or other insects.

“We know that more than 95 per cent of our canola is grown from seed that is treated with a neonicotinoid, so we know that honeybees are being exposed to very low levels of these insecticides when they pollinate canola,” said Wood.

“At the same time, we also know that honeybees do very well on canola, that they are productive, and produce a lot of great canola honey.”

Keeping levels safe

“Beyond that level, then we could start seeing decreased honeybee production or decreased overwintering survival of colonies. But as long as we keep our concentration within that safe range, farmers will have the ability to protect their crops by using insecticides, and we will keep our pollinators healthy.”

A post-doc student in Wood’s lab will continue her research, looking at the level of neonicotinoids in honeybee colonies that pollinate canola and comparing them to ones that do not pollinate canola.

“We need more strong evidence to truly show what are the levels that honeybees are being exposed to in the pollen that they are collecting in the nectar,” she said.

Cutting winter losses

“It’s incredibly difficult for a beekeeper to stay in business when they are losing 50 per cent of their animals every year,” said Wood. “We urgently need to find some solutions to improve our overwintering mortality here in Canada.”

As it turns out, varroa mites — parasites that infest hives and feed on bees — liked the drought conditions last summer.

“Because of that warmer weather, the mites were able to build up, and the fall mite treatments were not as effective to bring those mite levels down,” Wood said.

Beekeeping in Western Canada is especially challenging because the field season is so short.

“It’s only four months of intensive beekeeping and maybe we can expand our research over the winter to look at the effects of varroa miticides on winter bees. We can be doing research in the winter as well as the summer.”

Wood and the others in her lab also helped develop veterinary oversight for beekeepers in 2018. Numerous medications require a veterinary prescription but many vets had no experience prescribing medication for bees.

“There became a need for more training of practicing vets in common honeybee diseases and how to prescribe antibiotics,” she said. “We were able to fulfil that need because we had kind of a head start.”

Infectious diseases

Wood and some of her team members have backgrounds as veterinarians, so their strength is in infectious disease research.

They are studying bacterial diseases in honeybees, including European foulbrood and American foulbrood.

“These diseases are mostly controlled by antibiotics,” said Wood. “We are investigating … the best ways for beekeepers to apply antibiotics to treat these diseases and control their spread in their operations and minimize the potential for antibiotic resistance.”

Her lab is also studying nosema, a gut parasite that afflicts honeybees.

“We’re looking at ways to improve diagnostics for that, so that beekeepers can more accurately diagnose when this parasite is becoming a problem in their colonies.”

The lab is using histology (looking at tissues using a microscope), something commonly done in human medicine as well as livestock, but not for insects.

“We’re trying to develop the histology of male bees (drones) to look at their reproductive organs and understand whether pesticide exposure could affect the development of their testes and use that in improving pesticide risk assessments for the future,” she said.

The research relies heavily on the co-operation and participation of western Canadian beekeepers.

“Beekeepers have been very supportive — sending us samples, communicating their problems,” said Wood. “The research chair is just another person that can contribute to the existing research community and co-ordinate efforts so that together, we can really start to solve some of the challenging issues for beekeepers.”