If your greatest joy in farming is seeing nice, even emergence, you can’t beat a precision planter.

“We tried a bunch of pulse crops, including field peas, chickpeas, lentils, faba beans, soybeans, and we also tried it on irrigated durum and hemp,” said Farming Smarter researcher Gurbir Dhillon. “Seedling emergence and stand establishment improved across the board for all crops with the narrow-row (precision) planter.”

But looks don’t pay the bills when it comes to seeding equipment, and several years of Farming Smarter trials suggest it can be hard to make an economic case for a pricey precision planter.

Read Also

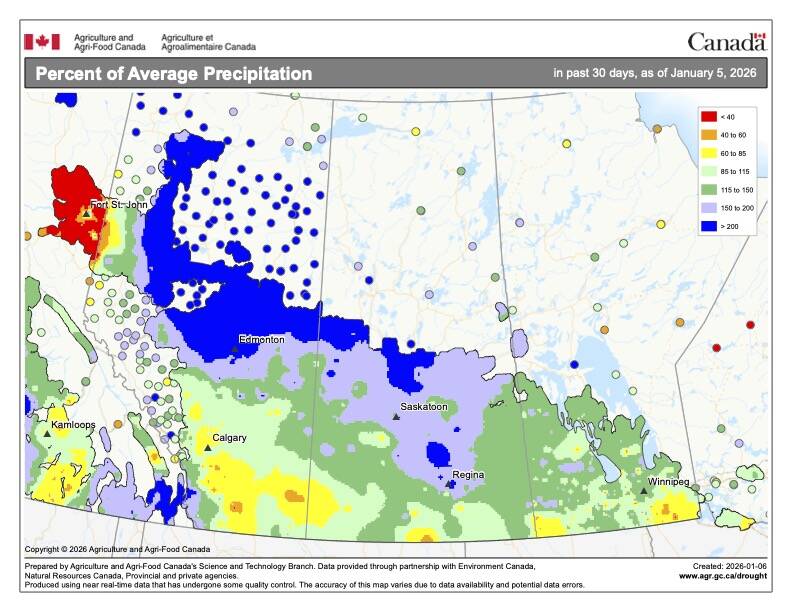

The lowdown on winter storms on the Prairies

It takes more than just a trough of low pressure to develop an Alberta Clipper or Colorado Low, which are the biggest winter storms in Manitoba. It also takes humidity, temperature changes and a host of other variables coming into play.

“We started this project with canola and we saw a yield advantage with canola, especially under irrigated conditions,” said Dhillon.

“(But) in the years with low rainfall, we didn’t see an advantage to the planters when it came to canola yield.”

Still, there’s a lot of interest in how a precision planter can perform. Some of that interest comes from producers who already have one because they’re growing corn or soybeans. Other farmers would like to see improved emergence rates, which should also result in more even stands at harvest time.

READ MORE: Precision planter research is encouraging

“Farmers wanted to be able to improve their canola emergence and they were interested in seeing if they could do it using the precision planter,” said Dhillon.

Farming Smarter researchers conducted trials at five dryland sites (at Lethbridge, Medicine Hat, Brooks, Taber and Enchant) over four years, using both an air drill and a precision planter to plant narrow rows (12 inches) and wide ones (22 inches). The narrow precision-planted rows had higher yields when rainfall was decent but in dry years that yield advantage disappeared.

It was a similar story for pulses, and yield advantages were not as consistent as in canola.

“In general, the planters yield better than the air drill or as good as the air drill,” said Dhillon.

The results were intriguing enough that if funding can be found, he would like to conduct further trials with a closer look at seeding rates.

“In the future, we do want to look at the better stand establishment with the pulse crop,” he said. “What’s the best agronomy to go ahead, especially with seeding rate? If there is better emergence with the precision planter, farmers may be able to cut down on their seeding rate.”

Farming Smarter researchers would also like to study pulse crops on irrigated acres.

“We want to see if there’s a similar advantage on irrigated production for pulse crops and what are the best systems that go with precision planting,” said Dhillon.

Fall seeding gets a test drive

Another ongoing research interest for the Lethbridge-headquartered organization is fall-seeded crops, a goal driven by southern Alberta’s ongoing soil erosion problem.

“We wanted to be able to keep the surfaces covered during that fall season so that wind erosion doesn’t remove the top inch of our soils,” said Dhillon. “One option is to go with cover crops, but fall seeding of some cash crops could be another option.”

The goal was to see how well crops established before freeze-up, how well they overwintered, and if there was an advantage in terms of using early spring moisture.

READ MORE: A few pointers on fall rye and winter wheat production

Researchers seeded fall rye, winter wheat, oats, lentils, barley, peas and camelina.

“Certain fall-seeded crops, such as camelina, showed a better ability to utilize early spring snow melt moisture, which was especially valuable due to drought conditions in 2021 and early spring 2022,” Dhillon said.

“Furthermore, despite the difficulties in controlling weeds in novel crops such as camelina and lentil cultivars, fall-seeded crops displayed a tendency to overpower weeds due to their early spring growth. Fall-seeded production can be a value option for many crops, specifically camelina, lentils and wheat.”

The test sites were in Lethbridge, Bow Island and Enchant — and location mattered.

“The establishment, growth and yield of fall-seeded varieties differed significantly between these locations,” said Dhillon. “The occurrence and duration of low soil temperature periods played a critical role in determining the overwinter survival of winter crops.

“According to the winter conditions observed in 2021-22, Lethbridge was found to be the most favourable location for winter crop production, followed by Bow Island.”

However, these observations are based on just one year of data.

The organization plans to continue the experiment once funding has been obtained. Dhillon especially wants to take a closer look at winter camelina because it showed potential. It was hardy, easily able to compete with weeds (and much better than spring camelina on that score), and also had higher yields.

“We’re planning to do two trials on the agronomic management of fall seeding camelina, and are just waiting for funding decisions,” said Dhillon.