It’s a common scenario.

A farmer has a field boundary that causes some headaches. Maybe it’s a ditch they figure is nursing crop disease, or maybe the ditch is a pain to navigate around. In response, the farmer drains the ditch or otherwise takes it out of commission.

Researchers recently completed an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada study on field boundaries in Saskatchewan and they don’t make judgment on that practice. Their goal is a compromise. How can the ecological value of trees, grass, wetlands and ditches be balanced with farm needs?

Read Also

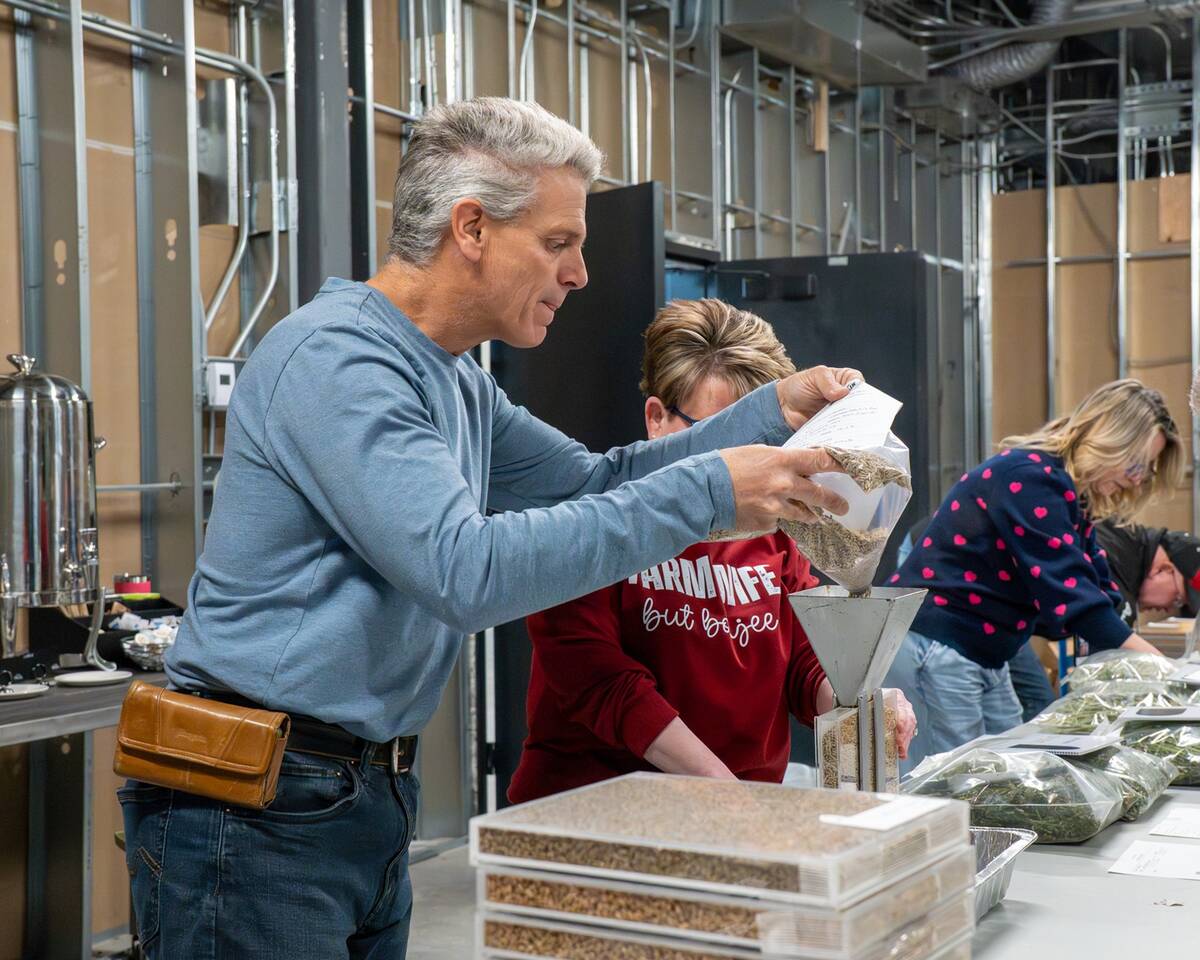

North American Seed Fair continuing a proud 129-year-old agricultural tradition

One of North America’s longest continually lasting seed fairs makes its 129th appearance in southern Alberta.

“This project is focused on understanding how field boundary habitats, including natural and planted boundaries such as shelterbelts, influence crop yield and quality, biodiversity, weed ecology and the broader agro-ecosystem,” project co-lead Shathi Akhter said via email.

The Swift Current-area researcher inherited the project from William Schroeder, a retired researcher with the Indian Head Research Farm who dedicated his career to studying shelterbelts on the Prairies.

He wanted to “expand the role of trees beyond crop production, aiming to quantify the ecological goods and services they provide regarding sustainability and resilience,” Akhter said.

“Recognizing the significance of this work, I have continued his efforts, documenting the diversity of field boundary habitats in prairie agro-ecosystems and assessing their potential beneficial and risky impacts on adjacent crops.”

Boundary habitats are cleared by farmers for a host of reasons, she noted, whether to increase farmland or due to a belief that they’re a source of weeds, pest infestation and disease spread. At the same time, she believes there’s a knowledge gap between those actions and the benefits locked into those habitats, such as biodiversity, fostering pollinators and potential yield gains.

“This research is crucial because it provides science-based evidence that can help farmers make informed decisions about managing these areas in ways that balance environmental health with farm productivity,” she said.

That balance can’t come soon enough, wrote co-lead Julia Leeson, a weed monitoring biologist with the AAFC research and development centre in Saskatoon.

“It is thought that the resulting habitat reduction has contributed to a loss of biodiversity and negatively impacted pollinators and other beneficial insects,” she said.Leeson was brought onto the boundary study thanks to her previous research on ditches bordering conventionally managed fields in Saskatchewan.

The boundary project is the first to document weed populations adjacent to shelterbelts and native treed areas in the Prairie region, she said. It is the second phase of a larger project dating back to 2017.

Researchers tapped the fields of 10 farmers in the Indian Head area of central Saskatchewan. Research was broken into two categories: weed diversity and spread; and impact on crop production.

“By studying the types of weeds that thrive in both natural and planted field boundaries, we can determine their potential to spread into adjacent crop fields. This includes analyzing how weed seeds are dispersed and how they might contribute to the soil seed bank in nearby cropland,” Akhter said.

“We are also investigating whether the presence of these field boundaries increases or decreases the weed pressure on crops. This is crucial for determining if these habitats are net contributors to weed infestations or if they play a more complex role in the ecosystem that might even benefit crop production.”

The project’s expected outcomes include new knowledge on weed ecology, guidance for farmers and gauging the economic and ecological benefits.

“Ultimately, this research is part of a larger effort to evaluate the role of field boundary habitats in sustainable farming,” said Akhter. “We are investigating whether these areas can be managed to reduce the need for chemical inputs, support beneficial species and improve overall farm resilience against environmental challenges.”

Data analysis is now underway. Leeson said preliminary observations suggest that even though common weed species may be present in field boundaries, their presence did not outweigh farmers’ ability to control them within the field. As a result, boundary type did not influence weed populations beyond field edges.

Leeson conducts field surveys throughout the Prairies to learn which weeds cause problems for farmers. She is involved in the prairie weed survey, which takes place over a four-year period with more than 4,000 fields visited across the three provinces.

She hopes data collected in the field boundary project builds on and verifies the data generated by the prairie survey, which she said has used the same methodology for the past 50 years.

“The field boundary project gives us a better understanding of weed populations in field margins (and) may help us explain changes in the prairie weed survey data,” she wrote.

The project is being funded by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and the Ministry of Saskatchewan through the Agriculture Development Fund and is cost-shared through the federal-provincial-territorial Sustainable CAP program.